The metropolis of Bengaluru, once celebrated as a garden city, is now grappling with the loss of its green spaces, leaving its dwindling lakes as the last line of defence against urban heat. Citizen groups deeply committed to preserving these lakes, have actively engaged in restoration efforts despite challenges like conflicting stakeholder priorities.

This is Part 3 of a three-part Citizen Matters explainer series on Bengaluru’s lake systems.

- Part 1 explores Bengaluru’s lake system, highlighting its functions and features.

- Part 2 focuses on the assets of a lake, including core zone assets (ecological assets) and social zone assets (recreational assets).

- Part 3 examines the management and interconnection of these assets, emphasising how citizens can support lake sustainability through audits and tree censuses.

One of the things that makes the situation particularly challenging is the management of interdependent assets and the multiple jurisdictions that govern different aspects.

Bengaluru’s lakes have transitioned from serving agricultural irrigation and fishing to being used primarily for recreational purposes. Control of these lakes has shifted from farmers to government departments, and their focus has moved from agriculture to industry and services, significantly impacting their role and usage.

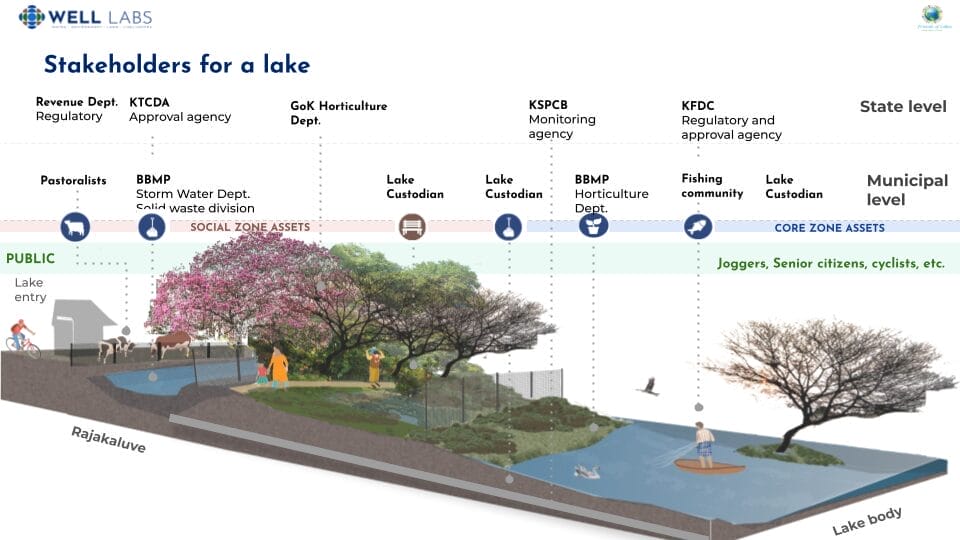

As the roles and uses of these lakes have evolved, the management of their assets is now categorised based on their various functions and the several entities involved: organisations, government agencies, and citizens across municipal, state and local levels.

In the earlier parts of this series, we have seen how effective classification and maintenance of these assets enable urban lakes to perform their ecological and recreational functions, fostering a sustainable urban water system that benefits both people and the environment.

Governance of assets

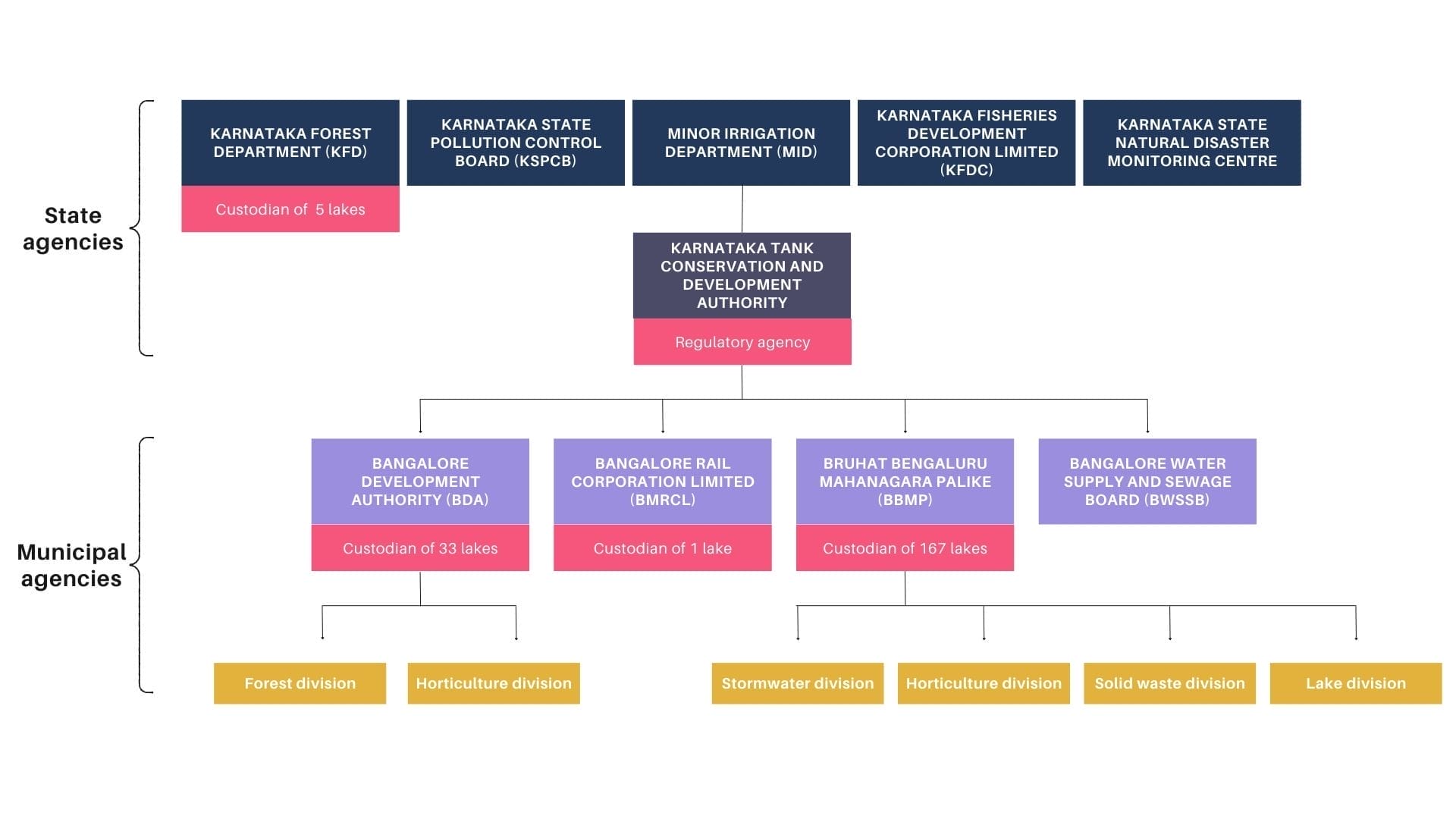

Collaboration between agencies is vital for holistic lake management. A list of all the government departments and various groups/entities involved in management of Bengaluru’s lakes can be found here.

Core zone assets are often managed by ecological or water management authorities, while social zone assets are overseen by municipal or recreational departments.

Read more: Bellandur Lake rejuvenation: An urgent call for action

Citizen initiatives, the way forward

In 2011, BBMP, the custodian of most Bengaluru lakes, partnered with NGOs through MoUs to manage 13 lakes, fostering significant citizen involvement in restoration efforts. Many citizen groups collaborated with BBMP, both formally and informally. However, this progress got stalled when a Public Interest Litigation (WP 38401/2014) in the Karnataka High Court challenged the MoUs, leaving citizen-led lake groups in uncertainty as their agreements were not renewed. Appeals by these groups have seen repeated delays in hearings.

Meanwhile, BBMP introduced the Kere Mitra project a year ago to promote transparency in lake management, but that too has faced several criticisms by the civic groups. Disputes over differing stakeholder priorities and the definition of lake assets persist.

Nevertheless, citizen involvement is crucial for preserving Bengaluru’s remaining lakes and trees. Here are some steps you can take to evaluate the state of your neighbourhood lakes, which will help in its preservation:

- Lake asset audit

- Tree census

How to conduct a lake asset audit

- For the audit, visit your neighbourhood lakes and observe the state.

- Refer to the audit checklist below to guide you. Note/document the different parameters

- Take photos to cover all aspects. Upload photos here or mail it to sandhya@oorvani.in in this format < Lake name, caption, photographer name> in the file name.

Lake details to be captured

- Name, area in square kilometres, jurisdiction, location, GPS coordinates.

- A brief intro about the lake: Where the lake lies and prominent areas/localities that come under this lake. Mention historical & cultural context.

- It can also include other details like presence of industries, type of industries, slums and hutments.

- Also include known challenges faced in the lake and its vicinity: floods, riots, crime.

| Ecological zone | |

| Interceptor channel | |

| Sluice gate at inlet and outlet | |

| Silt trap | |

| Debris trap | |

| STP | |

| Wetland | |

| Stabilization pond | |

| Lake body | |

| Aerators (diffusers, pedaler, fountains) | |

| Bund | |

| Rock lining of the bank | |

| Islands | |

| Weirs | |

| Borewells | |

| Jackwells |

Read more: How to do a tree census: Ambalipura Lake volunteers’ experience

How to conduct a tree census

The flora around lakes are very much part of the ecosystem needed for lakes to survive. With Bengaluru’s green cover dwindling due to urbanisation, the focus on conserving native trees has become more urgent than ever. Native trees not only support local biodiversity but also adapt better to the region’s climate and require less maintenance.

Unfortunately, many of the city’s lakes are being transformed into manicured landscapes, prioritising aesthetic appeal over ecological value. To truly revive these ecosystems, it is essential to emphasise planting and preserving native tree species around lakes.

The 7-acre Lower Ambalipura Lake provides an inspiring example of how a group of dedicated citizens is maintaining the neighbourhood lake, while ensuring that native trees thrive in its surroundings, resisting the trend of artificial beautification. Efforts by citizens here extended beyond planting to creating a detailed repository. Each tree was tagged, photographed with GIS coordinates, and documented with its taxonomy to raise environmental awareness and sensitivity. Here is an excerpt on how the lake tree census was conducted:

Tree Census Methodology

The team divided the lake into four quadrants – North, South, East, West and Island region. Then they started checking each tree with a minimum height of 2.5 metres. The identified trees were tagged with GIS information such as:

- Sl No., e.g: BALAS082 (BA – Bangalore, LA – Lower Ambalipura, S – South, XXX – Serial No)

- The common name, e.g., Indian Beech Tree

- Botanical name, e.g., Millettia pinnata

- Family, e.g., Fabaceae

- Kannada name, e.g., Honge mara

- Origin of the species, e.g., Native

These audits enable citizens and authorities to monitor the precious few surviving lakes, helping to prevent encroachments, sewage contamination, preserve biodiversity, reduce fish kills, and enhance monsoon preparedness, among other essential benefits.

Data from Bengaluru’s Lake Assets survey done as part of the Oorvani Civic Learning Hub – Lakes Masterclass in 2023 is published here.

According to news reports, BBMP is undertaking yet again another operation to remove illegal constructions in Bengaluru, specifically in the buffer zones of lakes. Unless citizen stakeholders are involved, the chances of success seem dim.

[This has been collated from proceedings and resources shared at Oorvani Foundation’s Bengaluru lakes audit jam.]