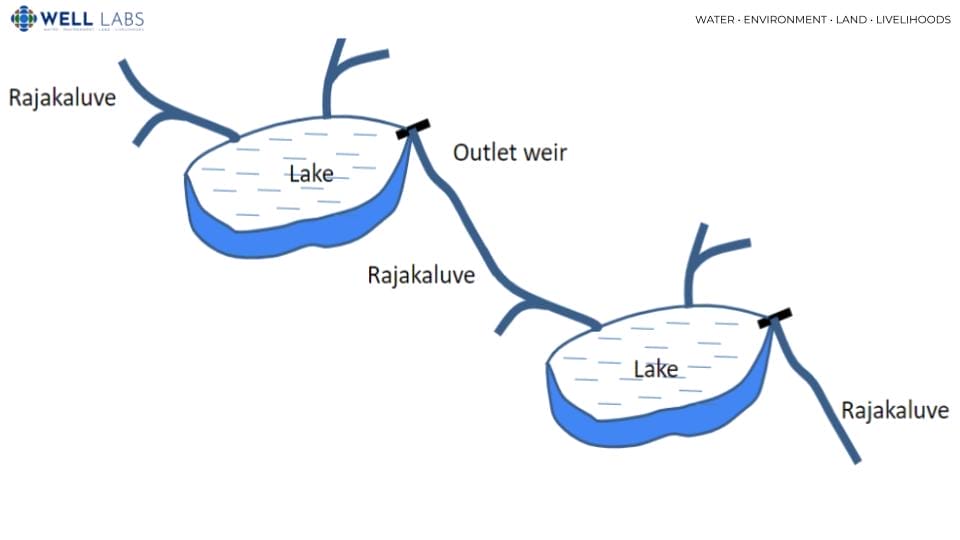

Bengaluru’s lake system is a distinctive feature of its urban landscape, shaped by the city’s unique topography. It is designed to manage its water resources effectively. Divided into three main valleys — Hebbal Valley to the north, Koramangala-Challaghatta Valley to the south and southeast, and Vrishabhavathi Valley to the west and southwest — the city’s lakes form interconnected cascades that enhance water storage, control floods, and recharge groundwater.

This is Part 1 of a three-part Citizen Matters explainer series on Bengaluru’s lake systems.

- Part 1 explores Bengaluru’s lake system, highlighting its functions and features.

- Part 2 focuses on the assets of a lake, including core zone assets (ecological assets) and social zone assets (recreational assets).

- Part 3 examines the management and interconnection of these assets, emphasising how citizens can support lake sustainability through audits and tree censuses.

These lakes, varying in elevation, land use and the extent of urbanisation around, represent a vital element of Bengaluru’s environmental and infrastructural framework. However, over time, modifications such as encroachments, water quality degradation, and altered flow patterns have impacted their functionality:

- The Hebbal valley, being less urbanised, features shallower lakes

- Koramangala-Challaghatta (KC) Valley is moderately urbanised.

- In contrast, the Vrishabhavathi Valley is the most urbanised, with deeper lakes that reflect the area’s extensive development.

Read more: The Secret Life of Bengaluru’s Lakes: A look at their history and the current situation

Functions of the lake system

Despite these variations, Bengaluru’s lakes continue to serve multiple primary and secondary roles, ranging from water storage and flood mitigation to ecological support and recreational use. This overview examines the structure, functions and asset management strategies of Bengaluru’s lake system, highlighting its significance in sustaining urban ecosystems and balancing developmental needs:

Primary functions of lakes

These include water storage, flood control and groundwater recharge:

- Water storage : Lakes act as reservoirs, storing rainwater for future use. Historically, they were crucial for providing drinking water, irrigation, and other domestic needs.

- Flood control: By temporarily holding excess rainwater during heavy rainfall, lakes help prevent urban flooding. The cascading nature of Bengaluru’s lake system allows controlled water flow between lakes, mitigating sudden water surges downstream. Lakes with adequate storage and functioning infrastructure (like sluice gates and bunds) significantly reduce flood risks in densely populated areas.

- Groundwater recharge: Lakes naturally replenish aquifers, ensuring sustainable groundwater levels. Water percolates through the lake bed, feeding underground water tables, which is vital in water-scarce regions. The extent of recharge depends on the lake’s design, depth and surrounding soil type.

Secondary functions of lakes

These enhance the ecological, social and economic value of these water bodies:

- Ecological support: Lakes provide habitats for diverse flora and fauna, including aquatic plants, fish, birds, and other wildlife. They maintain ecological balance, supporting urban biodiversity. Wetlands around lakes act as natural filters, improving water quality by trapping sediments and pollutants.

- Livelihood support: Lakes contribute to livelihoods through activities like fishing, agriculture, and cattle grazing. Informal economies, such as vendors and local industries depend on lake water.

- Recreational and cultural use: Lakes offer spaces for leisure, like walking trails, gardens and birdwatching areas. They often hold cultural significance, being venues for local festivals and community gatherings.

Read more: The Secret Life of Bengaluru’s Lakes: Envisioning a future

Interconnected nature of functions

The interconnectedness of Bengaluru’s lakes and the consequences of disrupting have been well-documented. A CAG audit for the period 2013-14 to 2017-18 highlighted that the uninterrupted flow of water through drains and lakes is critical to preventing urban flooding; however, a large number of drains (and lakes) in the city have simply disappeared!

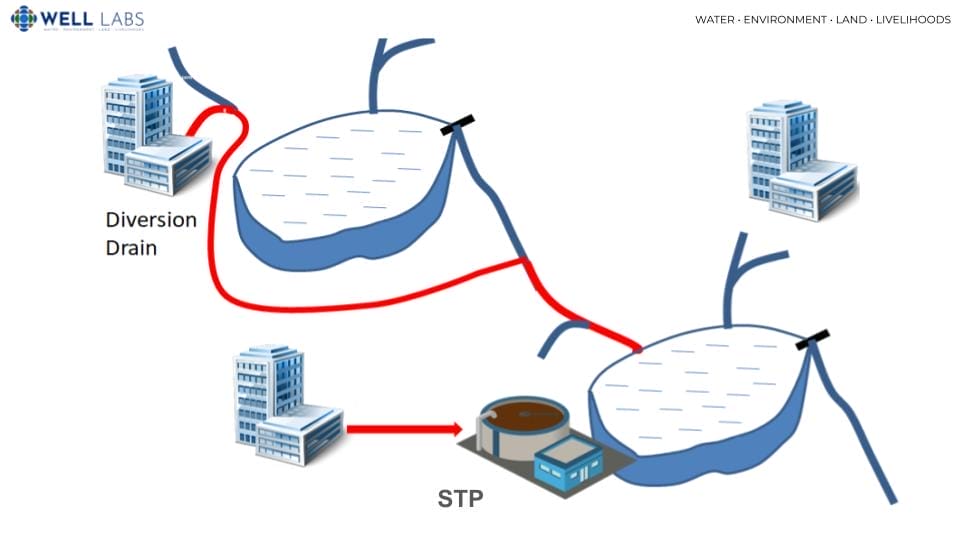

- System-level impact: Alterations to one lake can affect others in the chain. For example, a blocked rajakaluve may prevent water flow to downstream lakes, disrupting flood control and groundwater recharge. The cascading system ensures that the roles of individual lakes contribute to the larger water management system.

- Balance between functions: Managing competing priorities is key. For example, recreational developments (like concrete pathways) might reduce percolation, impacting groundwater recharge. Understanding and prioritising primary versus secondary functions is crucial for sustainable lake management.

By protecting and maintaining these functions, lakes can continue to serve as vital natural resources in urban ecosystems, balancing environmental health and urban development needs.

[This is the first part of the excerpts from Rashmi Kulranjan’s presentation at the Oorvani foundation Bengaluru lakes audit jam]

Only Zero discharge policy for sewage can make our rajakaluves and lakes clean again. Only clear and pure rain water should flow in our rajakaluves.

There are practical technologies available now such as https://aquatron.se/ which can be implemented at community level, or at individual home level, or even individual toilet level.