In Bengaluru, people lose 3-4 hours every day in commute thanks to heavily congested roads. Despite having public transport options including BMTC and Namma Metro, the traffic congestion remains unresolved. The NITI Ayog’s 2018 report estimates that Bengaluru city incurs an avoidable loss of Rs 47,743 crore every year.

What is wrong?

The real reason is that good mobility relies on a vast number of measures, most of which are missing. A few of these steps were attempted, but they failed due to improper execution.

This article explains what these measures are, and suggests how to implement them effectively in Bengaluru.

For a detailed explanation on mobility measures in general, read these explainers:

Part 1: Urban planning measures

Part 2: Transportation planning measures

Part 3: Traffic control measures

What are mobility measures?

Mobility measures are implemented in the form of policies, strategies, regulations, bye-laws, standards, plans and procedures. In addition, some nodes show natural urban processes that must be controlled (e.g. urban sprawl, regeneration).

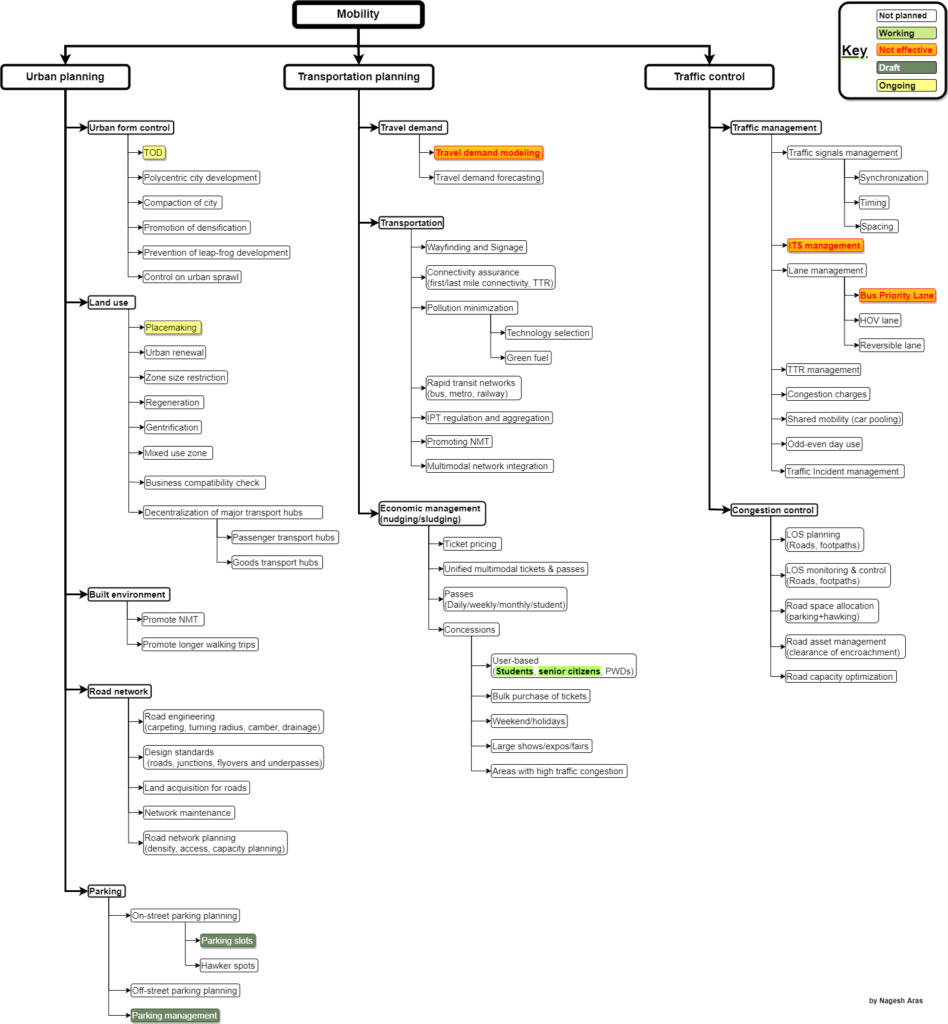

The following chart shows the mobility-related measures. It shows that our government has failed to implement most of these measures. That’s why we face daily traffic jams despite spending huge amounts on infrastructure such as Metro.

As shown in the chart, the measures can be logically split in three groups: Urban planning, transportation planning and traffic control. This article summarises them.

Read more: “Unplanned development failed the ORR. It may fail Peripheral Ring Road too”

The Urban Planning measures

The city planners must take measures that control and change the shape of the city itself, by controlling the urban form, land use and design of individual neighbourhoods.

Typically, these measures span a very large area (city-wide in most cases), and require very large budgets. They are implemented over a very long period.

Urban form control includes compaction (where building inside core is encouraged) and densification of the city (in which low-rise housing is discouraged and highrise buildings are encouraged). Control on land use ensures that workplaces and residential zones are evenly distributed across the city so that the city does not experience asymmetrical traffic rush.

Measures are also taken to ensure that the city has adequate roads to accommodate our vehicles, and a grid of roads so that when any given road has congestion, people can find alternative routes easily.

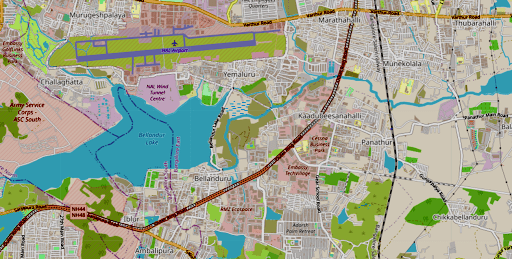

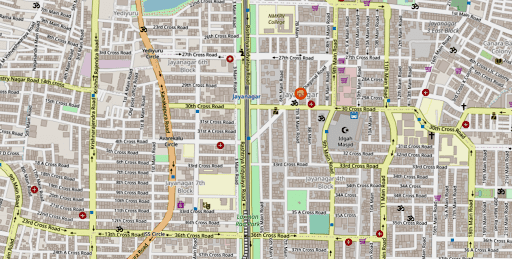

For example, compare the Outer Ring Road with the well-laid grid in Jayanagar 4th Block:

- The ORR does not have any parallel roads at all. And yet it hosts about 40 giant tech parks, besides serving as the only road that interconnects large traffic sources such as the International airport, Whitefield, and South Bengaluru (Jayanagar, JP Nagar, Banashankari and Electronic City). As a result, it suffers from perennial traffic jams.

- In Jayanagar 4th block, a dense grid of wide roads are available. Here, a motorist can easily take a side lane if the road ahead is congested.

Proper infrastructure is created to encourage people to walk or use bicycles for local trips. Localities are designed to encourage community cultural/sports activities in public spaces, which also encourage people to avoid motorised transportation.

Finally, on-street parking is controlled to ensure that roads remain obstacle-free. Parking availability is restricted to deliberately nudge people to use public transport.

Transportation Planning measures

These measures plan and manage the transportation-related infrastructure.

The first step is to measure the travel needs of people for their daily needs: work, education, shopping or entertainment. A forecast is also made to assess how these needs will change in the future.

Based on this assessment, multimodal transportation is planned (bus, metro, ferry, trains, etc.). Such networks are integrated tightly so that a person can switch modes within a trip to save time or money. For example, interchange stations to allow a person to switch between bus and metro. Special attention is given to make public transport affordable, fast, safe and reliable.

Since private transport (cars/two-wheelers) takes up a lot of road space and causes congestion on the city roads, the government offers economic incentives to lure people to use the public transport.

Traffic Control measures

Even if all the measures described above are implemented, traffic will eventually build up on the city roads. Therefore, adequate traffic control measures are needed. This includes planning and managing traffic signals and lane management. For example, reserving lanes for buses (Bus Priority Lane) and high-occupancy vehicles, reversing a lane during peak traffic to increase the road capacity in one direction, etc.

Also, we must implement measures to control congestion by judiciously allocating the road space for parking and hawkers in such a way that the carrying capacity of the roads is not reduced below the desired target value.

Why are these measures not taken?

The main reason is that there is no general awareness about these measures. The government agencies, activists and NGOs rarely discuss the need for these measures to be implemented in a holistic manner.

Secondly, the implementation is fragmented among multiple government agencies. Many of the measures are interdependent. And yet different measures are handled by disparate agencies without any coordination among them. For example, Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) requires partnership with agencies that provide the infrastructure like electricity, water, sewerage, and gas. But these agencies are not invited to plan the TOD zones jointly.

In some cases, the approach itself is flawed. For example, parking is treated as a simplistic “supply-and-demand” issue; in which the government proposes to provide maximum-possible parking across the city. This strategy would backfire: If parking is available freely across the city, people will keep using their own vehicles, and contribute to the congestion. Instead, parking must be deliberately made scarce, so that people are nudged to use public transport. For example, if we reduce the minimum parking required at workplaces (e.g. software parks), most of those employees would not be able to bring their own cars to the workplace. Thus a lot of single-occupancy cars would stop plying on the roads, which would reduce the congestion.

Read also: Bengaluru’s proposed Parking Policy actually encourages private transport

Fourthly, the interdependence of the measures is not considered at all. For example, if we make parking space scarce in the city, it will increase the demand for bus and metro sharply. This calls for a coordinated planning between the BBMP, BMTC and BMRCL. They must prepare a joint strategy carefully, anticipate public reaction and act in a specific sequence to achieve the desired outcome without a public outcry.

Finally, the lacklustre performance of all agencies is due to the fact that no agency is made responsible for any measurable outcome. Since the responsibility is distributed, no one is under any pressure to perform. The blame game protects all agencies!

The organisational issues

The agencies that handle mobility are not structured well, which affects their effectiveness.

All the agencies that handle mobility/transportation – DULT, BBMP, BDA, BMRDA, BMTC, Metro, KSRTC, Railways) are headed by IAS officers. These senior officers are on deputation, and they are not accountable to anyone for their organisation’s performance. Neither the Mayor nor the Municipal Commissioner have authority over them. This makes it impossible to control and coordinate these agencies.

Some activists favour the Metropolitan Planning Committee (MPC) model, where a central body plans and manages all urban matters. However, the problem with this idea is that most of the measures are handled by parastatal agencies or companies (e.g. Metro). Therefore they are not under the purview of the municipal corporation. In fact, in the 74th Amendment, the issues of mobility and transportation are not in the scope of the urban local body at all (refer to the 12th Schedule in the Constitution). Thus, this proposal is not in accordance with the Constitutional framework.

The Climate Resilience program (C40 Cities) relies on the Mayoral power for its success. However, this is probably modelled after European cities, where the Mayor is the Chief Executive, and runs the administration in a presidential system. In contrast, in Indian metros, the Mayor does not have all-encompassing powers.

Proposed solutions

From the preceding discussion, the solutions are clear:

The focus must shift from budgets and activities to outcomes. The agencies must become result-oriented, and must not keep themselves busy with ineffective rituals.

1. Assign all measures to specific agencies

All the measures shown in the chart must be made mandatory. Each measure must be assigned to one or more specific agencies. Each agency must be asked to announce its target outcome on an annual basis. All agencies must be asked to do a unified annual planning to achieve specific outcomes.

For example, BMTC and Metro must declare an annual target to increase their share of the city traffic by x%, backed by a systematic plan to achieve it.

The interdependence of the measures must be identified, and all the relevant agencies must be mandated to work together to achieve the common objectives. For example, if BBMP fails to keep its footpaths clear, people walk on the road, which affects the average bus speed for BMTC. Thus BMTC depends on BBMP to clear certain roads to achieve a certain target Level of Service (LOS).

2. Set up unified planning, control and command

We need tight technical coordination and data-sharing among the technical staff of all agencies. Clearly, this calls for sweeping organisational changes and also sharing of common infrastructure such as data servers, MIS and dashboards.

3. Set metric-based goals for all agencies

Devise metrics for all the measures, and make every agency accountable for specific metrics.

The planning must be done jointly, because the success factors of one agency are typically under the control of another agency. Thereforefore, every agency must ensure that its own metrics are achievable by demanding certain guarantees from the other agencies.

For example, Bus Priority Lane (BPL) cannot carry the target number of passengers if other vehicles enter the BPL lane and slow it down. Therefore BMTC must ask for a guarantee from the Bengaluru Traffic Police (BTP) to keep the BPL clear of other vehicles. In this case, BTP’s success is not measured in terms of the number of violators caught or fines collected, but in terms of how many vehicles still violate the rule. Because of this demand, BTP would be forced to use more effective tools like the Intelligent transportation system (ITS) to catch every single offender.

4. Set up a realistic reporting structure

Since all mobility agencies are headed by IAS officers, a senior IAS officer may be appointed as the nodal officer who presides over all agencies, and gets them to perform.

Public bodies like UMTA/BMLTA have only an administrative role, but they cannot take the onus of implementing any of the measures. Still, these bodies can monitor the metrics and ensure that all the agencies perform at their peak, and deliver the desired outcome.

5. Open up traffic data

The traffic data must be made open data, so that researchers and volunteers can analyse the data and suggest improvements. Not only raw data, but the MIS and dashboard must also be freely accessible by the public.

The open data will also help supply chains to fine-tune their logistics. Thus open data can not only eliminate the huge congestion loss, but actually boost our economy, and improve our quality of life!