With general elections in the country underway, all political parties have promised to prioritise public transport.

The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party promises to launch an “Urban Mobility Mission,” one of whose aims is to “increase the use of public transport.” On similar lines, the Indian National Congress says it will formulate a “policy on urban transport” that emphasises public transport including “metro rail, suburban rail, public bus transport” and non-motorised transport.

Yet, despite these stated aims, transport policy and investment remains resolutely oriented towards road building and private vehicles, particularly in Bengaluru, as evidenced by the controversial elevated corridor project championed by the Chief Minister.

The Karnataka State Assembly election manifesto of the Indian National Congress, which is a part of the ruling coalition in Karnataka, promised to ‘increase the (mode) share of public transport to 80 percent’ in Bengaluru, in line with the National Urban Transport Policy. Clearly, its support for the “elevated corridors” project is inconsistent with this objective.

While the election manifesto of the ruling Janata Dal (Secular) in the 2018 Assembly elections talked about providing assistance to municipalities for urban road construction, there was no mention of any urban highway mega project like the “elevated corridors.” Yet that project is being fast-tracked and prioritised over other transportation initiatives.

| All MP candidates say they want to promote public transport, improve infrastructure and reduce traffic congestion. Those from Congress say the Elevated Corridor project is the need of the hour. While BJP MP candidates on the campaign trail now are questioning the project on different aspects, in the state legislature, BJP MLAs had also supported the elevated corridors. |

Bengaluru: The road to nowhere

Bengaluru is notorious for its traffic jams. Average traffic speeds have dropped precipitously in the recent past — as much as 14 percent in the last year alone to a record low of 17 km/h. But even this is fast compared to some roads like the Outer Ring Road (ORR) where traffic crawls at below average walking speed. Alongside this, the number of vehicles looks all set to cross 1 crore, bringing with it a massive increase in distance travelled by vehicles and associated polluting emissions.

Clearly, there are too many vehicles on our roads slowing down traffic to abysmal levels. So why not just build more roads to make room for all the vehicles that are out there?

So far, this has been the thinking of the authorities in Bengaluru. There have been innumerable road widening schemes over the years. During the last half-decade or so, yet another fixation has taken hold, that of developing so called “signal free corridors” by replacing junctions with flyovers and underpasses. This has left our city covered with a web of flyovers and underpasses creating an intimidating environment for the pedestrian, but has delivered scant benefits to mobility as witnessed by growing commute times and falling travel speeds.

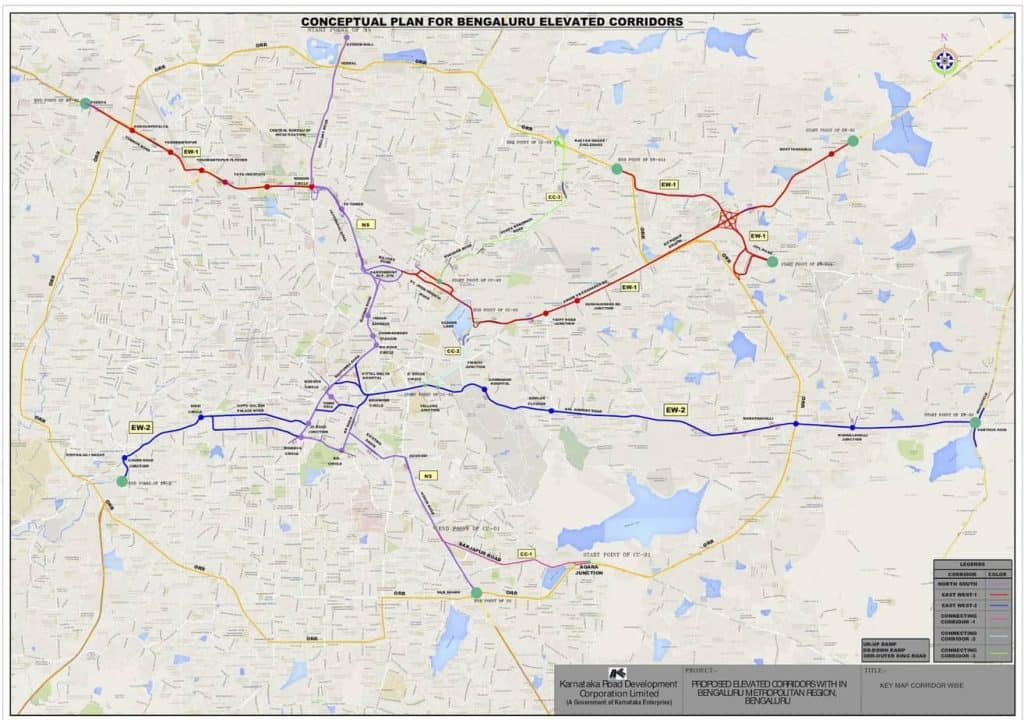

The latest scheme is for about 100 km of “elevated corridors” criss-crossing the city. Will this be the solution that Bengaluru needs? Or will it just add to our woes?

The plan has aroused much opposition, principally on environmental grounds that it would lead to greater vehicle usage and hence more polluting emissions and that thousands of trees would have to be cut down to build these new roads. Other grounds for opposition are that it would lead to more petroleum consumption which is not readily available in India and concerns over equity – that it privileges the few who use cars rather than the many who walk and use public transport.

On the other hand, proponents of the plan argue that enabling traffic to flow smoothly rather than being stuck in stop-start traffic would reduce fuel consumption, emissions and consequent pollution. To address the issue of equity, as incomes rise, more people would be able to afford private motor vehicles, and finally even that building elevated roads for private vehicles would allow buses to run faster on the ground level roads.

However, there is a more fundamental flaw with these plans. There is a wealth of evidence that building more roads does not reduce congestion or improve mobility. Even under idealized conditions of a fully electric fleet of vehicles affordable to the vast majority, conditions that might become possible in the future, a road based solution will not be viable for Bengaluru.

Induced traffic demand

Most people are familiar with the idea that if the price of something goes down, its consumption increases as more people are able to afford more of it.

It turns out that a similar logic applies to roads. Increasing road capacity to reduce traffic congestion and increase travel times would be beneficial only if the same number of vehicles made the same number of trips as before. But it turns out that the new capacity results in people making more trips than they did before, thereby negating any advantages of the additional road capacity, and in fact increasing petroleum consumption and polluting vehicle emissions.

A useful analogy to explain the principle is ‘liquid’ vs ‘gas’. Historically, traffic was assumed to be like a liquid, that is, a certain volume flows through the pipes, and so expanding the pipes would let the liquid get through more easily without backing up. However, traffic is more like a gas that expands to fill the available space.

The immediate effect of adding road capacity is to reduce congestion and thus increase traffic speeds. This induces people to make many kinds of trips in their private vehicle that they did before because of high congestion. For example, travel to new destinations like a supermarket or restaurant several kilometres away becomes more attractive. Similarly, with reduced levels of traffic congestion, using the car for a short trip that was earlier done by walk, bicycle or public transport might become more attractive. Soon, the volume of traffic expands to fill up the new capacity, restoring congestion to previous levels.

Reduced congestion also affects long term decisions such as where to live. With higher travel speeds, living further away from work becomes more viable. Over time, this results in greater urban sprawl and automobile-dependent development. The dispersed development pattern makes public transport less viable, and wider roads and increased traffic volumes in turn degrade the pedestrian environment, leading more people to shift to the use of motorised private transport.

Induced demand exists: Cases from around the world

Several studies, around the world, have quantified the results of expanding highway capacity.

In 1994, the British Standing Advisory Committee on Trunk Road Appraisal report found that reducing travel time on highways by 20 percent increases traffic volumes by 10 percent in the short term and 20 percent in the long run. As a result they concluded, “the economic value of a scheme can be overestimated by the omission of even a small amount of induced traffic. We consider this matter of profound importance to the value-for-money assessment of the road programme.”

In 1998, the Surface Transport Policy Project, a survey of 70 metropolitan areas found that regions that invested heavily in road capacity expansion did not do better in terms of road congestion compared to regions that did not. Several more recent studies have found similar results. Just this year, Kent Hymel of California State University, USA found that vehicle miles travelled increases in exact proportion to road capacity expansion, and that any congestion relief from capacity expansion vanishes within five years.

Thanks to such studies, most countries around the world take the effects of “induced demand” into account while planning any road expansion. For example, the US Department of Transport now assumes that a 10 percent decrease in a combination of travel time and expense results in traffic volume increasing by 8 percent in 5 years, and an additional 2 percent in 10 years.

In India too, the experience appears to have been similar. Professor Ashish Verma of IISc, Bengaluru says, “Mumbai has built many flyovers and the Worli Sea Link. But the city is more congested than it was earlier.” Talking of Bengaluru, Srinivas Alavilli, co-founder of the group Citizens for Bengaluru says, “We have nearly 50 flyovers in the city and three elevated corridors. If these are the solutions, then they have failed because we still have traffic problems.”

Furthermore, all these studies assume a fixed population and a fixed number of vehicles overall. Bengaluru’s population is increasing, and ever more people are able to afford private vehicles. So if people have to drive to get around, any new road capacity will fill up much more rapidly than indicated in these studies. In fact, Professor Verma has estimated that the proposed elevated corridors will fill up in less than five years.

Loose ends

Unconvinced proponents of the elevated corridors may poke holes in the argument. Bengaluru has some specific problems, they would argue, that would be mitigated by the elevated corridors.

Gridlock, for instance. This refers to instances of substantial traffic backing up in streets to block intersections, thereby stopping traffic flow. Unfortunately, the Victoria Transport Policy Institute finds that more urban highways would actually increase the chance of gridlock, “Gridlock can be avoided with proper intersection design and traffic law enforcement. Increasing regional highway capacity tends to increase this risk by adding more traffic to surface streets where gridlock occurs.” Anyone who has seen traffic jams at points where flyovers or underpasses end can easily relate to this finding!

What about the argument, made by R.K. Mishra, a member of BBMP’s Technical Advisory Committee and the person who proposed these elevated corridors? Mishra said that by reducing traffic congestion by creating extra road capacity through elevated corridors, buses can move faster and provide reliable service.

At best, this is a recipe for managed decline of bus services. Clearly, all those who could afford it would use their own vehicles to speed through the elevated corridors, instead of using the slower buses on surface streets and having to deal with an unfriendly pedestrian environment. With growing incomes, more people would acquire their own vehicles, and ever fewer would use buses.

Present day Los Angeles, criss crossed by highways, serves as a good example where most travel is by automobile with only residual service provided by buses on surface streets. The highways, though, have not reduced traffic congestion imposing huge costs. But it wasn’t always like that. Before they built the highways, Los Angeles had one of the most extensive tram networks in the world, which went into terminal decline before being shut down altogether.

The Harbor Freeway, California State Route 110, in Downtown Los Angeles during afternoon rush hour. Multi-level roads filling up with new traffic. Pic: Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0

What should be done instead?

Rather than focussing on reducing congestion for automobiles, our attention should be directed towards avoiding traffic congestion and enabling alternative forms of mobility, so that people’s travel needs are not stymied by traffic congestion.

Even though this may sound counterintuitive, the way forward might be to reduce, rather than increase, road capacity. Reducing road capacity and reallocating the space for exclusive bus lanes would transport more people using the same space, and with a lower environmental footprint. Similarly, investment in rail-based transport can help improve mobility for a lower environmental impact.

Over the last decade, Seoul in South Korea has torn down dozens of elevated expressways and used some of the newly freed land to increase green and blue cover. The result has been a 3.6 degree centigrade reduction in peak summer temperatures. As each summer gets hotter than the one before, Bengaluru would certainly appreciate some relief in this regard!

The real and sustainable solution to our problem here is a greater focus on public transport, not more investment in roads that have failed to work so far and are guaranteed to fail in future too.

| This article is part of a series produced under the Citizen Matters – Sustainable Cities Reporting Fellowship and supported by Climate Trends. |