This article is part of our special series Environmental Sustainability & Climate Change in Tier II cities supported by Climate Trends.

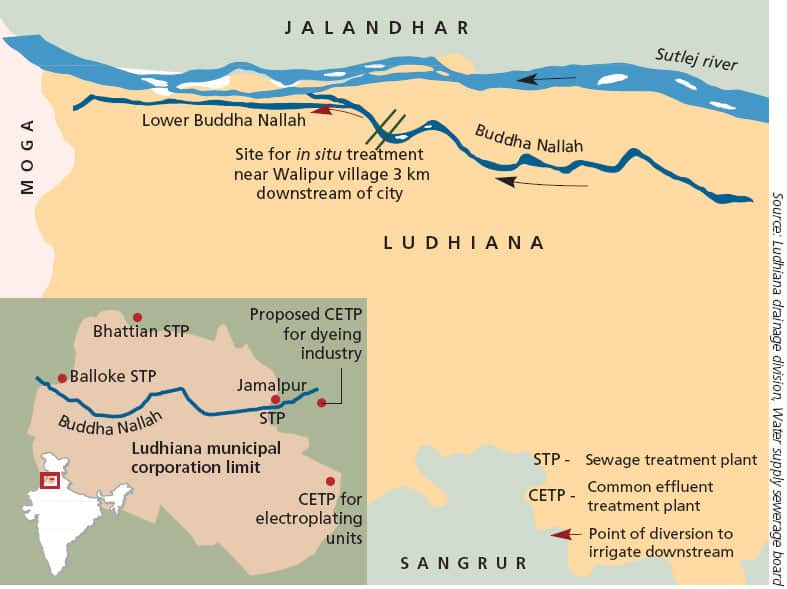

The life sustaining character of the Sutlej river has changed drastically in recent years. Symptomatic of Sutlej’s sorry state is the Buddha Nullah, a 14-km stream that runs through Ludhiana, picking up toxic effluents in massive quantities and around 200 MLD of untreated sewage a day, in its passage through the city before dumping it all in the Sutlej.

Sutlej which originates at the Mansarovar lake in Tibet, flows through Himachal Pradesh and Punjab covering a distance of 1450 kilometers, before crossing over to Pakistan. In what has long been described as the Land of the Five Rivers, the Sutlej has been the main source of water for irrigation and drinking purposes in its 440-km journey through Punjab.

Till a decade or two ago, the river had brought prosperity to the districts of Ropar, Ludhiana, Jalandhar, Kapurthala, and Ferozepur. But the massive inflow of untreated sewage and industrial effluents into the river in recent years has now turned it into a source of disease and disaster, especially after it crosses Jalandhar and Ludhiana, Punjab’s industrial and business capitals.

“The Buddha nullah accounts for 90 per cent of the pollution in Sutlej river,” says K S Pannu, Punjab’s Director of Environment and Climate Change. The contaminated water is further distributed through canals for irrigation in the entire Malwa region of the state and parts of Rajasthan.

“It was I think in 1977 or 78, I was in Class 7. Both banks of the Buddha Dariya used to be a place for social gatherings. My father used to take all of us as kids there, and some of the best memories of my childhood are of those outings”

Arun Chatwal, Resident.

A Punjab Agriculture University study had found the presence of mercury, cadmium, chromium, copper, and other carcinogens in vegetables and crops grown in villages along the length of the nullah. After the confluence of its water into Sutlej, the river’s water attains the Class E status in terms of pollution, meaning not fit for any use and does not sustain any aquatic life.

“Buddha Nullah is the most dangerous and toxic water body in Punjab, which affects the lives of over 2 crore citizens in Punjab and Rajasthan,” says Sant Balbir Singh Seechewal, a well known environmentalist. Sadly, it was once a clear water stream and “the centre of social life in Ludhiana”.

Increasing temperatures, depleting water table

The high level of pollution in the Buddha Nullah has led to large scale deforestation along its banks. “During the pre-industrialization days in the 70s, the banks of the nullah were significantly cooler than the rest of the city,” says Jaskirat Singh, an environmental activist. “But now, temperature in that area has gone up as compared to elsewhere. It is largely on account of the high level of toxic chemicals, pollutants, and dairy sludge, which contain micronutrients which release heat, as they flow down the nullah”.

Old time residents of the city too say that summer months have become much hotter over the past 40 years. As per a 2015 study done by D K Grover and Deepak Upadhyaya of the Punjab Agriculture University, the average temperature during the summer months has increased by 1.2 to 2 degree Celsius in the last 15 years, which is significant compared to the average global temperature increase of 0.5 degree Celsius.

Today, the city’s residents are entirely dependent on groundwater to meet their drinking water needs. The nullah has led to the contamination of groundwater along its entire course, which has led to frequent outbreaks of diseases. “The entire population of Ludhiana is at risk,” says a local doctor Arun Chatwal.

“From 40 feet, the water level has gone down to 500 feet at most places”

Sant Balbir Singh Seechewal, an environmentalist.

“Most people in Punjab are dependent on groundwater for drinking purposes,” says Seechewal. People dig borewells and draw water out with hand pumps and electric motors. But this comes at a huge environmental cost, especially in the depletion of groundwater levels. From 40 feet, the water level has gone down to 500 feet at most places.

Much of the population and animals in villages along the course of Sutlej river do not have any alternative but to drink the river water, putting their lives at risk. “If only the Buddha Nullah could be cleaned, it would have saved a huge amount of resources for the state government”.

A PETITION FROM JAIL

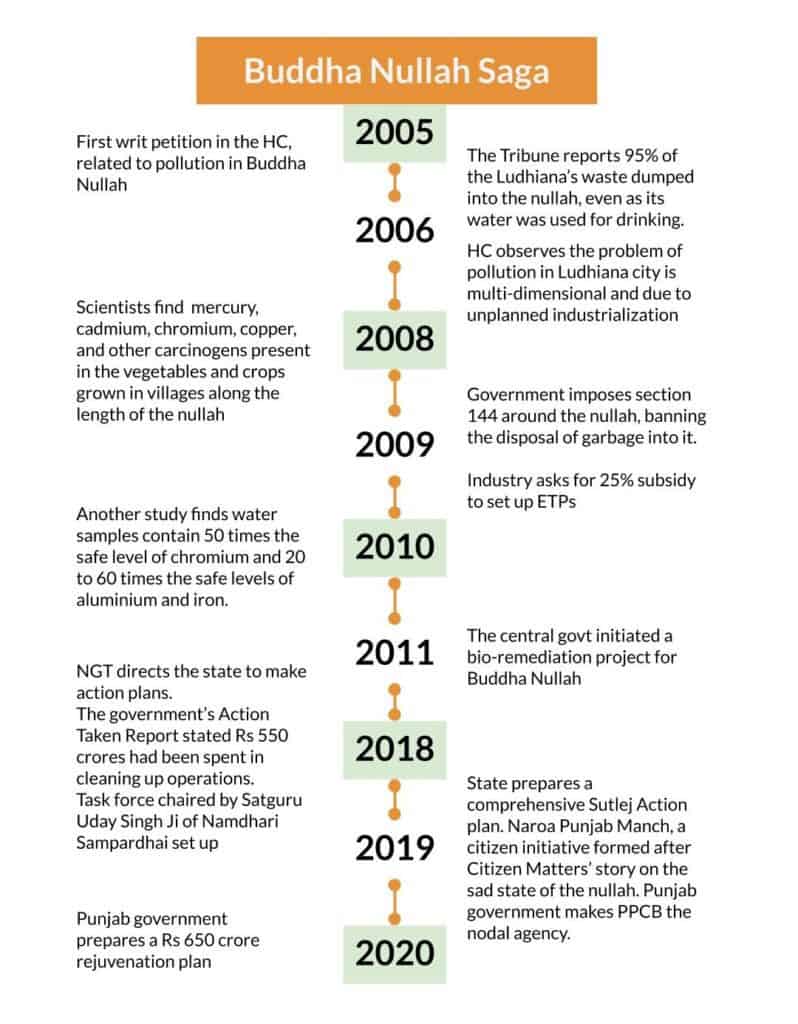

Many writ petitions concerning Ludhiana and the Buddha Nullah, have been filed before the Punjab High Court. The first such petition, CWP No.7036 of 2005 titled ‘Nirbhai Singh v. State of Punjab’ in which suo-motu notice was taken, originated out of a complaint from a prisoner of Central Jail, Ludhiana. In his letter to the Chief Justice, Nirbhai Singh, serving a 10-year rigorous imprisonment sentence, stated that jail’s inmates suffer from chest/cough ailments and itching in their eyes, thanks to the smoke emitted nearby. This case brought out issues of industrial pollution as well as the city’s garbage dumped in landfills on the river bank.

The long saga

There have been any number of committees and recommendations to clean up the nallah. For instance, the P Ram Committee had filed 10 status reports over a decade ago (between 2007 to 2010), and recommended treatment plants for industrial effluents and sewage and a comprehensive sewerage system for the city.

The nullah gets effluents from textile dyeing and bleaching units and electroplating units, as well as waste from cattle sheds. In 2009, National Environmental Engineering Research Institute (NEERI), Nagpur studied the problem of wastewater treatment, and recommended setting up individual and common Effluent Treatment Plants, ensuring Zero Liquid Discharge into the water body. It also said treated water from Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs) be used for irrigation.

Buddha Nallah carries pollution caused by untreated industrial effluents and domestic sewage from 16 outlets to river Sutlej. Some actions mentioned in The Sutlej action plan:

- Stop direct discharge from dairies in Tajpur Road

- Rehabilitation of Jamalpur STP and setting up an additional unit of 50MLD capacity by 2020.

- Setting up two CETPs of 50 MLD and 40 MLD capacity

- Disconnecting domestic sewage outlets discharging into storm water sewers

- relocating slum colonies which were letting in untreated sewage into the nullah

- Upgrading ETPs of 14 large scale dying units

- Stopping dumping of solid waste into the nullah.

- Modernising slaughter houses

In 2018, the National Green Tribunal (NGT) directed the state to prepare action plans to restore polluted stretches of the river. The NGT panel asked the corporation to make Buddha Nullah garbage free, increase staff at sewage treatment plants, install CCTVs in the treatment plants along the nullah and to seal the points used by the MC for dumping raw sewage.

Despite allocations of large sums of money, all these recommendations have remained on paper. The situation is so bad that Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) and the Union Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF), classify Ludhiana as a “Critically Polluted Industrial Cluster”

No change in pollution levels during lockdown?

Now, in what civil society activists term as absolute lack of transparency while dealing with environmental issues, a strange case of pollution inversion has come to light in Ludhiana. The Punjab Pollution Control Board (PPCB) says that as per tests conducted by it during the lockdown period, pollution levels in the river increased marginally.

As per PPCB Member Secretary Krunesh Garg, the PPCB test results indicated that the BoD levels in Buddha Nullah, tested at its last point before it meets the river Sutlej, remained almost the same in samples taken on March 20 and April 20. The BOD levels however increased in the Sutlej 100 meters downstream after the confluence of Buddha Nullah, during the same period.

The report raised a furore as citizen groups and the Ludhiana Municipal Corporation questioned the PCB findings, even accusing the PPCB of trying to give a “clean chit to the industrial units, one of the biggest sources of pollution in the Nullah and thereby the river Sutlej,” according to Jaskirat Singh, a member of Naroa Punjab Manch and in the forefront of the Clean Buddha Nullah movement. “They should have been transparent and taken the samples in our presence,” added Ludhiana Mayor Balkar Sandhu.

Not surprisingly, the pollution control board is busy shifting the blame on to the municipal corporation. “We never said that industry doesn’t cause pollution in the Buddha Nullah,” said board member Krunesh Garg.

But even as the blame game continues, the fact remains that Buddha Nullah remains a toxic drain, one reason being the city government has not been able to operate the STPs optimally or shift the dairy units to outside the city.

Recent directions

In late 2019, the Dept of Science, Technology and Environment, GoP, issued directions to control the pollution, and made PPCB the nodal agency in charge. It said industrial effluents and dairy discharge be segregated and treated. The Municipal Corporation of Ludhiana had to set up STPs, setting up flow meters and CCTV for effective monitoring. The corporation had to set up ETPs and biogas units to process dairy waste.

Ludhiana has only three Sewerage Treatment Plants (STPs) with a total capacity of 311 MLD, against a capacity requirement of 750 MLD. Even these three plants are often non-operational due to technical reasons, which means that the entire raw, untreated sewage of the city is dumped into the Buddha nullah.

In January 2020, the Punjab Government firmed up a Rs 650-crore plan to clean up the nullah. However PPCB, the regulator, and Punjab Water Supply and Sewerage Board, the agency responsible for its implementation, have been going about it in a hush-hush manner without involving civil society or environment experts.

“It is a unique opportunity for the city. It will be disastrous if they fail to implement it properly this time,” said Garg.