Earlier this month, the automaker Ford announced its decision to close manufacturing operations in India, which at present are at Sanand in Gujarat and Maraimalai Nagar in Tamil Nadu. The decision sent what media has portrayed as ‘shockwaves,’ given that the livelihood of several employees is at stake.

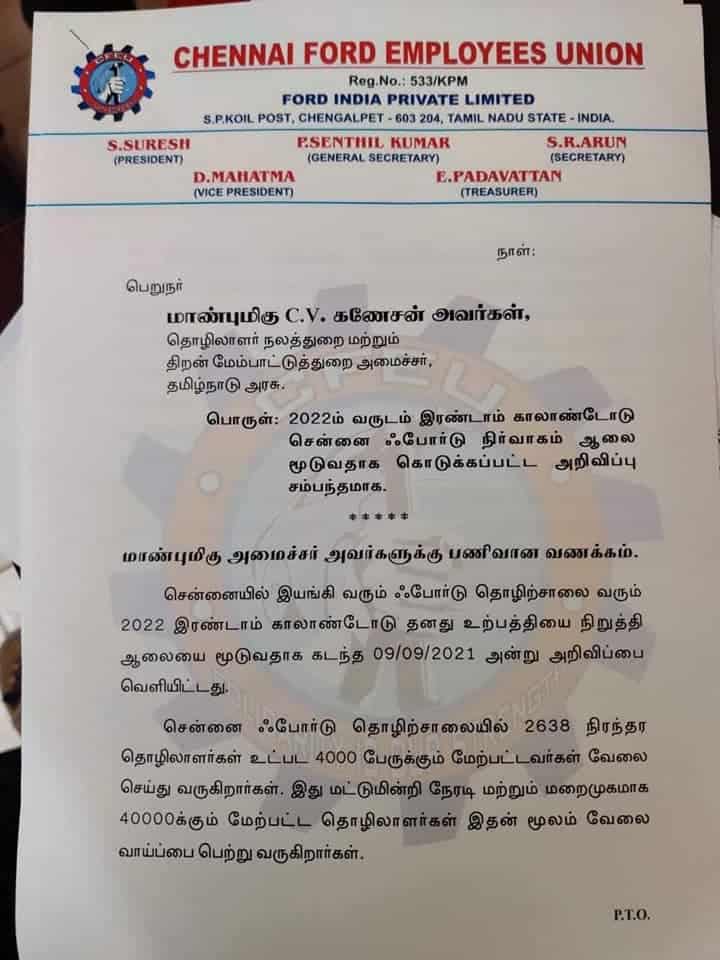

In Chennai, this will mean around 2,700 permanent employees and a few hundred contract staff will be thrown out of jobs. While that is no doubt regrettable, what cannot be denied is that this was bound to happen sooner or later, given the performance of the company in India. Also, what is surprising is that the reaction is wholly on predictable and rather outmoded lines – there is talk of inviting the Government to involve itself, the Union is protesting, and political parties are making hay, one way or the other. Elsewhere in the world, such a decision would have been taken as par for the course for a liberalised economy.

Read more: How COVID landed the MSME sector in Chennai in deep waters

Ups and downs in Ford’s journey

The re-entry of Ford into India, in collaboration with the Mahindras, was one of the highlights of the first wave of Indian liberalisation. For Tamil Nadu, and within it Chennai, it brought about many tailwinds – the existing automotive component industry received a boost and it also made the entry of Hyundai and several other companies a lot easier.

The plant’s inauguration was a high-profile event and since then, the setting up of other facilities such as an engine plant or an R&D centre has always had the ruling Chief Minister in attendance. While Tamil Nadu did have other marquee names in the auto sector, Ford was considered special.

What was often forgotten in all this hype was that the company’s performance was always below par. Its best was in FY 2018/19 when it posted a profit of Rs 526 crores, which incidentally saw the company returning to the black after ten years. But even then, year on year sales of vehicles were dipping. The last successful model launched by Ford in the country was in 2013.

Of course, the Indian plants also exported considerable numbers but that meant the company was subject to the vagaries of the international market. Globally Ford had embarked on cutting operations in what it defined as non-core markets (euphemism for being unable to withstand competition from Japanese and Korean automakers) and was withdrawing. It was but a question of time before it pondered over India. Accumulated losses of USD 2 billion would jolt any company into action. In any case, Ford is not alone. GM and Harley Davidson have also closed and moved on.

Read more: Newspaper distributors in Chennai fight COVID blues without any support

Impact of Ford’s exit

The impact of this decision will not be restricted to just those 2,700 jobs. An entire ecosystem comprising vendors, dealers and logistics operators is bound to be hit hard. The bitter reactions are therefore not out of place. But what is odd is the sudden call for governmental protection. We can either be a free-market economy or not. We cannot have the best of both worlds. If we rejoiced at the opening up of India in 1992, it also meant we were open to international pressures and business tactics.

Closure of non-profitable operations happens to be a harsh but real necessity in enterprises. Gone are the days when a Standard Motors could chug along, producing vehicles in single digits each month, sustained by promises of governmental aid which never came by the way. That is if you don’t include behind-the-scenes arm twisting of industrialists to step in as white knights. A more recent instance was the closure of the Nokia plant which happened in 2014. Despite all the protests the shutdown went ahead as per plan and it was only in 2020 that operations resumed, after a takeover.

It is time Chennai woke up to such possibilities. While inviting businesses to a state remains very much a part of a government’s responsibilities, getting them to stay is not. That depends on the performance of the businesses. Ultimately it is the market which dictates who remains and who leaves.

[This story was first published on the author’s blog. It has been republished with permission. The original article can be found here.]