Ragiri Sankara is a cab driver based in Bengaluru. “Tackling the heat is a huge task these days,” he says. To be driving all day in the heat is very tiring; the car heats up very fast. “I pack different juices daily to keep myself cool,” he adds.

Gig workers, street vendors, waste pickers, construction labourers, and the urban poor face a higher risk of heat stress than the general population. Now that summer has ended and the monsoon is setting in, the government has once again failed to effectively manage heat stress in Bengaluru.

The need for a localised HAP

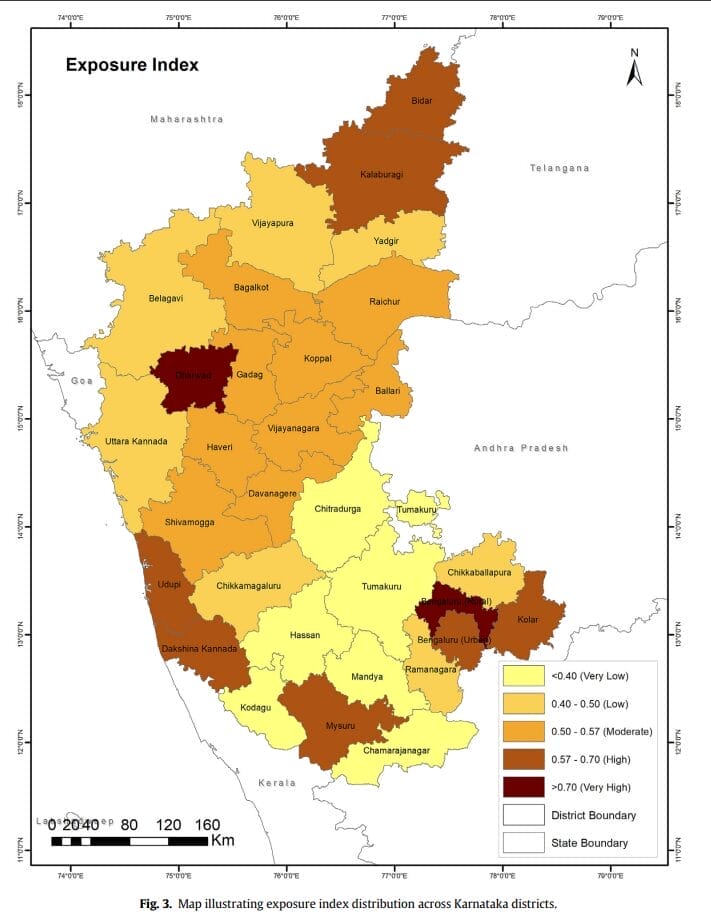

A study in The Journal of Climate Change and Health classifies Bengaluru Urban and Rural as moderate-risk districts. However, Bengaluru Rural faces the highest exposure, while Bengaluru Urban falls into the high exposure category. This underscores the need for localised data to assess heat stress impacts on different communities and develop targeted action plans. But Bengaluru does not even have a heat action plan (HAP) except for a state HAP.

Shruti Narayan, Managing Director-Regions and Regional Director-South and West Asia, C40 Cities, notes that localised ward-level heat stress assessments enable targeted, community-specific interventions by identifying areas of heightened exposure — often low-income neighbourhoods with poor housing, limited tree cover, and inadequate access to cooling resources.

Read more: Scorching streets: Understanding urban heat islands in Bengaluru’s market areas

How can localisation help

So, how exactly could a localised heat action plan help?

Vulnerable communities face greater risks due to age, health issues, and unstable jobs. For daily wage earners, lost productivity means lost income.

Ward-level data helps integrate lived experiences with technical mapping to inform inclusive planning that reflects local risk perceptions, access to essential services (such as health, water, electricity, housing and transport), and resilience capacities.

“Ultimately, it empowers communities to co-create solutions and advocate for equitable adaptation measures,” Shruti adds.

To give an example, she points out that granular ward-level data on the impact of heat on health is largely missing. Combining thermal imaging, qualitative interviews, and community engagement with spatial dataset analysis could be a potential solution. Similar mapping can be adopted for greening efforts.

Action is key

But implementing measures to combat heat stress is more important than measuring it. “It is not just important to measure the heat stress, we should look into how we can incorporate it to take necessary measures to protect the most vulnerable,” says Sobia Rafiq, co-founder of Sensing Local, an Urban Living Lab based in Bengaluru. Strategies to combat heat stress can focus on urban planning, green infrastructure, public awareness, and community engagement.

“Localisation provides an understanding of the problem and helps identify simple solutions that can later be scaled up,” says Sobia. Even for other weather events like flooding, settlements near raja kaluves or stormwater drains are more vulnerable, so actions like evacuation should prioritise these communities.

By analysing a locality’s built-up area and the types of jobs people do, we can identify communities most vulnerable to heat exposure. “But we can’t just be working on developing a database on this,” she adds. It is more important to implement actions side-by-side. Instead of relying on broad heat measurements, we need a localised, multi-dimensional approach to tackle heat stress.

When the government proposes strategies like cooling systems or shelter models, the private sector—such as architects and urban planners—can step in to suggest effective cooling solutions and shelter designs.

Identifying spaces for greening

Another localised measure could be improving green cover. Areas with more greenery are much cooler than those with dense construction. According to a study by the Centre for Science and Environment, the built area in Bengaluru has increased from 37.5% to 71.5%, while the green cover has only increased by 7.6%. To tackle rising temperatures, priority should be given to greening areas with less vegetation.

Localised healthcare accessibility

Health is also a vital component that must be incorporated in local heat mitigation plans, considering heat stress is the leading cause of weather-related deaths, according to WHO. Lack of accessibility to healthcare facilities for the urban poor is a major challenge.

In Bengaluru, 160 Urban Primary Healthcare Centres (UPHC) are functional in 198 BBMP wards, which is not even one UPHC per ward.

Therefore, the government must also prioritise improving access to healthcare especially during extreme weather events like heat stress. Also, should ensure that cost does not become a barrier for those in need.

Solutions to combat heat stress

“A vendor in Bengaluru supplies coconut leaves to put on top of roofs during summer to reduce the heat impact in households,” Sobia notes. And the demand increases every year. “This is a very simple yet interesting local solution that can be implemented even in houses in low-income settlements that do not have concrete roofs.”

So, here are some immediate local measures:

- Installing shelter models in public spaces.

- Subsidised cool-roofing systems in low-income households.

- Green nets over traffic junctions.

- Improved healthcare accessibility in wards that lack enough primary healthcare centres.

And some long-term mitigation measures could include:

- Developing hyperlocal data to map vulnerable communities and heat hotspots.

- Developing guidelines and SOPs for outdoor workers, gig workers, construction labourers, etc,.

- Increasing the green cover of the city, especially in areas which are more concretised.

- Improving access to drinking water in informal settlements that lack formal water connections.