Air pollution is now the leading cause of death in India. It accounts for 1.2 million deaths, more than the number of people killed by malaria, smoking or road accidents.

Last year, a study by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) found that Bengaluru topped the list of major polluting cities in India. More recently, measurements of pollution level using hand-held devices show that particulate matter pollution levels in many places in Bengaluru are substantially higher than the levels in Beijing, China and yes, even New Delhi.

More alarmingly, pollution levels in Bengaluru are expected to skyrocket over the next decade, as particulate matter concentrations increase substantially from already high and unsafe levels; nitrogen oxide concentration is forecast to more than double.

Prof. S K Satheesh, meteorologist and Professor at the Centre for Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru says, “In Bengaluru, vehicular emission is the major source of black carbon and particulate matter pollution. We do not have any major industries which can cause black carbon and aerosol concentration to go up. Although there are regulations on emissions from each vehicle, the number of vehicles is rising very rapidly.”

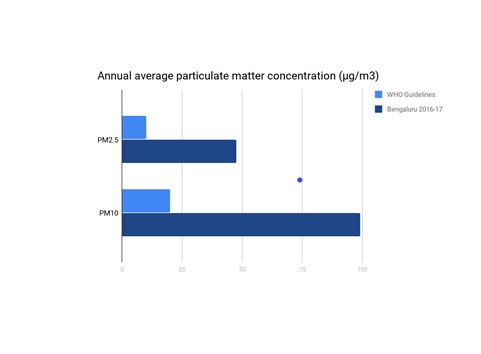

Annual Average particulate matter concentration in Bengaluru in 2016-17. Source: Air Quality Emissions and Source Contributions Analysis, Urbanemissions.info

What is wrong with diesel?

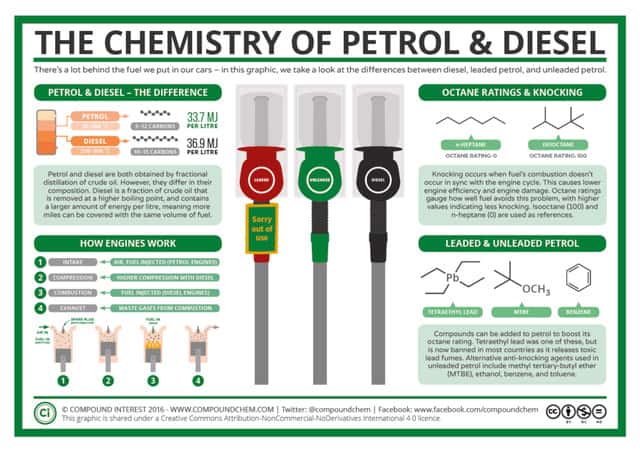

Both petrol and diesel engines work by burning fuel to generate energy which can then be used to move vehicles or to do other kinds of work. The combustion of any petroleum-based fossil fuel like diesel or petrol produces water, carbon dioxide and nitrogen oxides. But there are key differences between the way petrol and diesel engines work.

In petrol engines, a mixture of air and petrol is set alight by a spark plug. On the other hand, in diesel engines, combustion is initiated by compression. This actually enables them to use less fuel to produce the same power as petrol engines, thereby producing less carbon-dioxide too. However, the greater efficiency comes with a greater cost as diesel engines produce more of other pollutants, such as particulate matter and nitrogen oxides.

Diesel exhaust contains two principal types of substances – gas and soot particles. The gas from diesel emissions consists of carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, sulphur oxides, water vapour and organic compounds. The soot, on the other hand, contains carbon particles, organic compounds known as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and some metallic compounds.

High levels of air compression in diesel engines results in substantially greater production of nitrogen oxides compared to petrol engines. “Breathing in nitrogen dioxide increases the likelihood of respiratory problems,” explains Dr. Renu Ethirajan, MBBS, DNB (Pathology), a senior pathologist practising in Bengaluru. “Nitrogen dioxide inflames the lining of the lungs, reduces immunity to lung infections and can cause problems like wheezing, coughing, colds, flu and bronchitis.” She adds that it can be particularly damaging for people with asthma as it can increase the frequency and intensity of asthmatic attacks.

Soot or particulate matter produced in diesel engines “varies in size from coarse particulates (less than 10 microns in diameter) to fine particulates (less than 2.5 microns) to ultrafine particulates (less than 0.1 microns). Ultrafine particulates, which are small enough to penetrate the cells of the lungs, make up 80 to 95% of diesel soot pollution,” Dr Renu explains. “Mutagens (mutation causing agents) and carcinogens (cancer causing agents) are present in both the gaseous and particulate components, (and) lung cancer has been the focus of attention,” she adds.

Studies have demonstrated that people exposed to high levels of diesel exhaust over a sustained period show substantially higher levels of lung cancer and mortality compared to the general population. As a result, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has classified diesel exhaust as a Group 1 carcinogen, the highest level of classification.

“Health concerns about diesel exhaust relate not only to cancer, but also to other problems of the lung and heart,” warns Dr Renu. “Acute effects of diesel exhaust exposure include irritation of the nose and eyes, lung function changes, respiratory changes, headache, fatigue and nausea while chronic exposures are associated with cough, sputum production and lung function decrements. Additionally, it can cause inflammation of the airways whose effects can be extremely detrimental in asthmatics and those with compromised pulmonary function.”

She says there is also evidence indicating an association between diesel exhaust exposure and allergies. “Diesel exhaust particles can be shown to act as adjuvants to allergen and hence increase sensitization response.”

Diesel pollution in Indian cities

Besides affording greater fuel efficiency, diesel vehicles are also more economical to run, especially in India, where diesel has always been cheaper than petrol. They have thus been a popular option, especially for large vehicles like SUVs, which are also the most polluting. Earlier, diesel cars were favoured in several European countries too, because of their greater fuel efficiency. But in the wake of growing evidence of the health effects of diesel emissions, several cities are moving towards banning them altogether, a measure that several Indian cities would do well to emulate.

A recent study by the International Centre for Automotive Technology has shown that on-road emissions from Indian diesel cars differ from emissions under lab conditions. The researchers mounted portable emission monitoring equipment on cars and drove them around Delhi, finding that on-road emissions often far exceeded Bharat Stage IV emission norms, the Government of India’s standards for emissions that were then in effect.

The study also found that the on-board diagnostic system (OBD) provided in most cars failed to detect anomalously high emissions. Sports Utility Vehicles (SUVs) are the worst offenders with one diesel SUV accounting for nitrogen oxide emissions of about 25-65 petrol cars!

“India needs to adopt tighter test procedures and new driving cycle for certification of vehicles as soon as possible, it also needs to adopt real world driving emissions testing for both type approval as well as in-use compliance purposes,” says Anup Bandivadekar of International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), the lead author of the study.

The new standards due to come into effect in 2020, Bharat VI, impose more stringent criteria than previous versions. But it does not mandate on-road emissions testing which is now the norm in Europe and China. Experts believe this is essential to capture the real world impact of driving diesel cars.

Despite its shortcomings, the tightened regulations under Bharat VI have had their impact. Maruti Suzuki is phasing out small diesel cars by 2020 when the new regulations are set to come into force, while also considering phasing out other diesel car models.

For buses too, increasingly, there are alternatives in the form of hybrid and electric buses. In Bengaluru, the government plans to replace 6,500 diesel buses with battery driven electric buses in a phased manner over the next five years.

Freight Transport?

Another major source of diesel emissions is the transportation of goods from where they are manufactured to where they are consumed. As the economy grows, more and more goods need to be transported, and in India they are increasingly transported by road, most often by lorries producing toxic diesel emissions.

The share of freight carried by rail in India has steadily declined from 86% in 1950 to just over 30%. Several factors have been identified, in a study by the National Council of Applied Economic Research, as reasons for this decline. Extension of the rail network has been miniscule compared to the massive growth of the road network, freight charges have often subsidised passenger fares, diesel is available cheaply and lorries are often overloaded and can easily avoid penalties for violating regulations. Even when trains are used to transport goods over long distances, last mile connectivity poses a problem.

Thus even in cities like Bengaluru, we often see lorries plying on city roads at low speeds adding greatly to air pollution and noise. Additionally, they are often parked on narrow streets adding to traffic congestion and taking up limited space.

Elsewhere, this state of affairs has prompted innovative solutions such as goods trams. In several European cities, trams are being used to transport goods to places like supermarkets under the Tramfret project. Although most Indian cities do not have tram networks, using smaller electric vehicles for goods transport within cities can be considered.

There is growing evidence that increasing diesel use is causing higher mortality, besides a wide range of diseases. It is thus imperative that urgent steps be taken across the spectrum of passenger and goods transport to curb this menace.

| This article is part of a series produced under the Citizen Matters – Sustainable Cities Reporting Fellowship , supported by Climate Trends. |

I don’t think it will be required. The amount of time wasted on road due to poor road infrastructure and the number of vehicles already warrant that car is no longer the best option for personal mobility in Bengaluru. Hence, with no solution to the infrastructure problem, people have to gradually move to non road modes of transportation.

As you said that government plans for electric buses that are going to provide end to end connectivity and with the metro being finalized; don’t you think that the problem will solve itself when it will no longer be financially viable to move around the city in a car?