In 2019, a new underground drainage pipe (UGD) was installed to clear an earlier blocked sewer that erupted, leaked, and contaminated the land. The culprit – output from the unplanned growth of commercial kitchens in 5th block, Koramangala, which have been pumping these effluents into the UGD.

The Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB) moved the UGD from the carriage way to the side of the road, where all the utilities were planned, as part of the whitetopping procedure. They found that the discharge from the line that was attached to a restaurant was entirely filled with oil when excavating to build a new chamber.

Read more: Urban Utilities Map Beku: What lies beneath Bengaluru’s roads

Increase in eateries and cloud kitchens

Koramangala, like most of Bengaluru, has witnessed an explosion of eateries from small home run enterprises, often run from garages to large microbreweries and fine dining restaurants. It boasts its own khao galli (food street). Even pandemic-induced lockdowns have not dampened the business as most of the eateries are on delivery platforms.

According to an IMARC report, India’s online food delivery market size reached US$ 36.3 Billion in 2023, which is an increase of over 200% compared to 2022. Delivery platforms have mushroomed over the last few years, which has given rise to cloud kitchens, along with traditional restaurants, which have come up all over the city.

Many of these kitchens operate in unhygienic conditions. In 2019, The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI), the statutory regulatory body of the food sector, came up with a new self assessment scheme titled Hygiene Rating Scheme (HRS), focused on food preparation and handling, which has come under criticism.

Apart from food preparation and handling, the question of disposal also needs urgent focus.

Read more: Cloud Kitchens: Existing regulations on quality, safety not enough for this new format

Commercial kitchen contaminants

Urban Commercial Kitchen is a very lucrative business, servicing medium to heavy table occupancy, online food orders, and ODC (outdoor catering). Some of them also have a centralised kitchen catering to their chain of restaurants across the city.

These commercial kitchens produce a lot of waste – solid and liquid waste. The solid waste is collected by BBMP, but the liquid is disposed of into the sewer lines (BWSSB UGD) or worse, stormwater drains (SWD).

A large part of the liquid waste from these commercial kitchens comprises Fat, Oil and Grease (known as FOG) or Fatbergs. These fats, oil, grease or food debris from food prepared on a massive scale and cleaning up of food equipment, utensils and crockery, etc. end up in the UGD or SWDs.

Fatbergs block sewers

A congealed mass of oil and grease from cooking mixed with non-biodegradable items, such as tissues, wet wipes, etc, create a solid mass with a texture similar to concrete. These build-up over time and leads to a total sewer blockage, which causes raw sewage to spill from drains into streets and homes, causing public health problems.

Solution: Grease management

In addition to causing obstructions, fatbergs can cause environmental harm and infrastructural damage, as seen by the now infamous Bellandur and Varthur lake frothing. They are time consuming and costly to remove and are harmful.

In order to reduce FOG contamination, worldwide three different types of grease management systems are used to either trap or treat wastewater:

- Oil and Grease Trap (OGT) – A device which helps intercept, trap and remove oils and solids from kitchens

- Grease Removal Units (GRU) – Grease removal units are automated units consisting of the same initial function of a grease trap with additional processes, which remove food debris and FOG into external containers for separate disposal

- Dosing Systems – These add enzyme or biological (Anaerobic Digestion) elements to the drainage system that is designed to break down the FOG into less harmful products.

All of these options are only effective if they are properly maintained. A combination of all of these options can be implemented.

Whilst KSPCB guidelines mandates such grease traps in STPs, it should however, mandate it for commercial kitchens, malls with large food courts, banquet halls, Kalyana Mantapa, Matha’s community kitchen, and all food processing establishments.

Disposal mechanism for grease trap waste

“Controlled waste” is a term used to describe the waste that builds up inside a grease trap or GRU. Consequently, only a recognised trash contractor should be in charge of it. An anaerobic digestion method (process through which bacteria break down organic matter) is a preferred option for final disposal.

The missing link is that the controlled waste disposal mechanism is not enforced by the authorities – BWSSB or KSPCB.

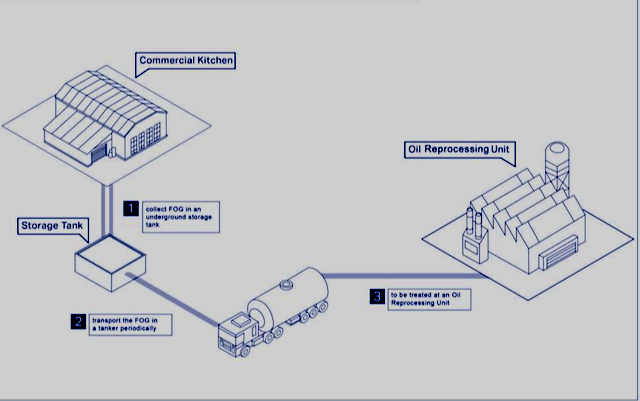

A simple and cost effective solution, which can reduce the stress on BWSSB’s STPs and help our cities, is to create an underground storage tank (OGT/GRU) to collect the FOG from commercial kitchens, which is then transported via a tanker and taken to an oil re-processing unit.

As a pilot project, Nagarjuna Restaurants in Koramangala is implementing this at their central kitchen. If this succeeds, it will be replicated across the city.