This article is part of our special series Environmental Sustainability & Climate Change in Tier II cities supported by Climate Trends.

In May 2018, 51-year old Shail Bala Sharma, an Assistant Town Planner (ATP) was shot dead at Kasauli –a popular hill station and cantonment in Solan district, known for its quaint colonial buildings and landmarks. She was out to enforce a Supreme Court order to demolish half a dozen illegal constructions in the town, mainly hotels, lodges and guest houses.

Hotelier Vijay Singh, whose hotel was slated for demolition, allegedly opened fire on her and the accompanying town and country planning (TCP) team and fled the spot. He was arrested from Mathura three days later.

The incident, the first of its kind in the state, tragically highlighted the problem of illegal constructions and mushrooming growth of unplanned urban settlements under the nose of the government, which is now finding it extremely difficult to take corrective action.

“It’s really unfortunate that some people have no concern about the vulnerability of the places they live in,” said Raaja Bhasin, a Shimla-based historian and author. “Officials responsible for enforcement of the regulatory mechanism also lack sensitivity about the heritage value and natural surroundings of urban towns. So this mess in the hills kept spreading. To correct things now is not going to be an easy task.”

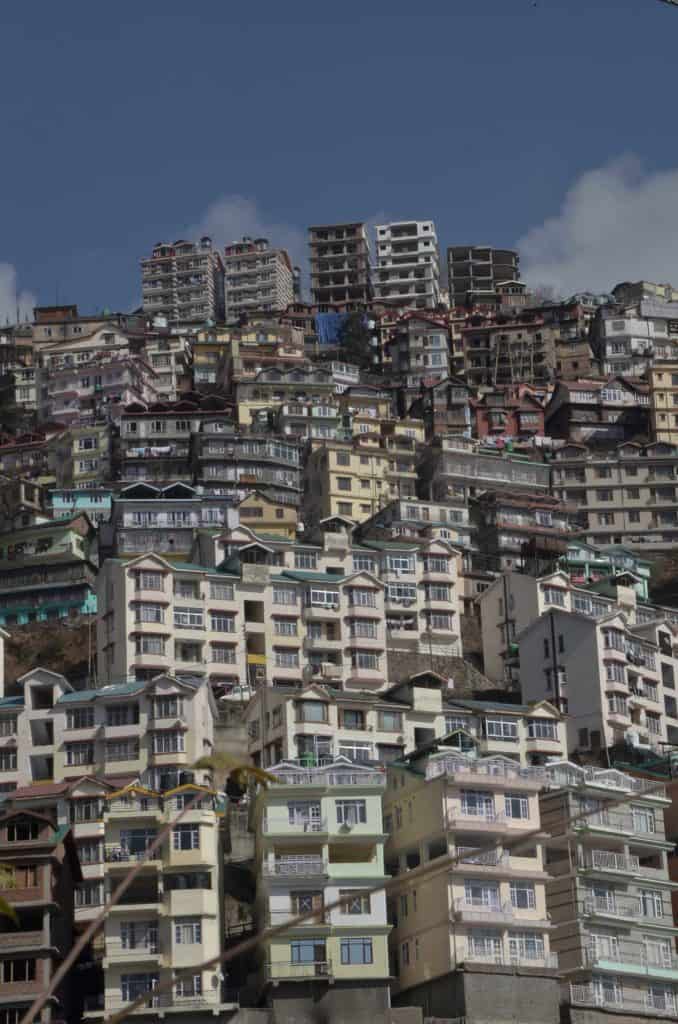

The haphazard boom in construction activities in the hill towns is mainly due to urban migration and population growth. Most towns in the state have greatly exceeded their carrying capacities.

Planning be damned

Risks to life and property from natural disasters stemming from climate change have grown manifold. The ever increasing influx of tourists and resultant over commercialisation of existing properties — by converting them into hotels or other business enterprises — have added to the risks.

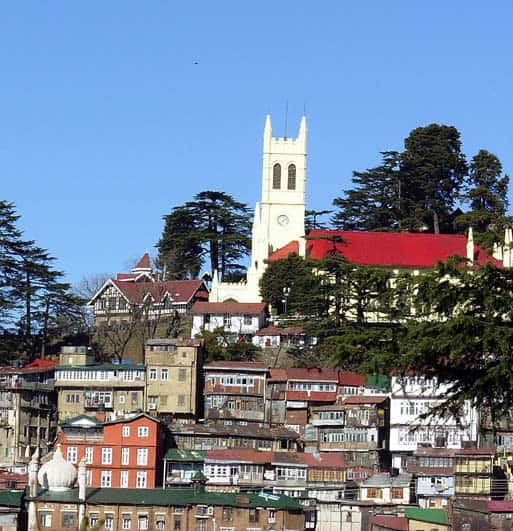

Shimla, of course, has been repeatedly quoted as a classic example of the dangers of such expansion. Regulations and bylaws governing civil constructions have been amended and ignored with impunity.

As it is, its open spaces meant as playgrounds and recreational areas and natural drainage channels have been taken over by residential and commercial buildings. The forest cover and scenic slopes in and around the town are now concrete eyesores.

Shimla’s older citizens share their genuine concerns about declining snowfall, increase in summer heat and winters shrinking to just few weeks. Shimla’s green cover is now limited to some patches of protected Jakhu hill—a core Shimla belt overlooking the Mall road apart from Annandale forest, Shimla’s downhill area and some 17 patches which were notified by the forest department in 2000 as the green belt in and around Shimla.

There is also a complete ban on new constructions in the green belt imposed by the state High Court in 2011 and 2014.

“As a child, we were afraid of walking through certain Shimla localities like Talland, Kaithu, Summerhill, Sanjauli and Navbahar as they were then dense forests with wildlife,” recalls Balbir Thakur, a retired IPS officer. “I have waded through five to seven feet of snow even in March. Today, the failure of enforcement leading to unplanned constructions, both illegal and legal, makes the town highly vulnerable”.

Rules be damned too

As per official estimates, there are more than 31,000 unauthorised buildings in major hill towns in Himachal Pradesh, with Shimla constituting 30 per cent of these.

The state government’s Town and Country Planning (TCP) officials admit that many buildings don’t meet safety and environment parameters, and have come-up in complete violation of the plans approved by the department or even without getting the building maps approved.

Strangely, Shimla does not have any master plan. Construction approvals were given as per the 1979 interim Shimla Development Plan. To suit political exigencies, successive governments, especially during the time of municipal and other elections, would amend rules to regularise unauthorised buildings to benefit their supporters. Nobody cared about the town’s heritage status, its natural surroundings and even impending climatic factors and its impact.

For instance, the maximum number of storeys per building has kept changing. There have never been any fixed limits on the height of buildings either.

The 11-storied Himachal Pradesh High Court is a telling example of high-rise structures on hill slopes. Other similar structures on hill slopes are the Jakhoo ropeway (13 storeys) and the Indira Gandhi Medical College (IGMC) hospital comprising seven stories. Other similar structures that did not take into account Shimla’s vulnerability assessment and effects of climate change are the police headquarters, PWD head office and the HP Secretariat‘s new Armsdale building.

Future at stake

Suresh Bharadwaj, Shimla MLA and minister for Urban development, who took-up the new portfolio only a fortnight back agrees that Shimla’s future is at stake and solutions need to be thought of urgently. “If laws are enforced strictly, we have to bring down several buildings,” said Bharadwaj. “This is not practical as even the waste generated through such demolitions have to be dumped somewhere. We don’t have space left even for this. This is the reality”.

Bharadwaj recalls the efforts of the earlier government to regularise the buildings through legislation which the High Court had struck down. The National Green Tribunal (NGT) too in November 2016 had imposed a series of restrictions and bans on future constructions in Shimla and other towns like Manali, Dharamshala, McLeodganj and Kasauli. But to little effect, it would seem.

“In the next few days, I will sit down with top officials and experts (including the environment department) to work-out some measures to save Shimla’s glory and also see that no future violations happen. Climate change issue cannot be ignored,” Bharadwaj assures.

Numbers tell the story

The data available with the MeT department in Shimla reveals that there has been 5 to 42% decline in rainfall since 2004. The deficit was 33% in 2019 and 24% in 2018.

During August 2020, there have been 21% less rains while June and July saw 26% and 28% less respectively.

Snowfall in Shimla has also shown major variations over the years. During December 2018, Shimla had only 7.1 cm of snowfall. It was 20.3% higher in 2019. The town had 70.4 cm of snow in January 2019 against 81.4 cm in 2018. However, 2020 has seen 96.6 cm of snow. In February 20, 2020, there was only 2.0 cm of snow as compared to 51.3 cm in 2019.

“Himachal Pradesh is witnessing a wide variation in temperature, rains and snowfall,” says Dr Manmohan Singh, Director, Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) Shimla. “The rainy days and periods of snowfall are shrinking. Also, the frequency of extreme weather conditions has increased.”

Encroachment of slopes

The most alarming fact is that some buildings have come up at steep slopes of even 40 to 60 degrees. These are mainly commercial buildings outside the urban town limits. Like guest houses, homestays, hotels and restaurants, multi-storey show rooms and also flats with markets. None of these builders have followed the floor-area ratio and height parameters and are structurally unsafe.

For instance, a multi-storey restaurant and homestay building at Kumarhatti in Solan district collapsed like a house of cards on July 2019 killing 13 army personnel who had stopped there for lunch. Subsequent inquiry revealed that the building had been built without proper foundation on a hill slope. An FIR was filed and a magisterial enquiry ordered, but no action was taken against the erring building owners.

In some towns, builders had even encroached on abandoned spaces which had been categorised by the Town and Country planning departmentas sinking and sliding zones. Nullahs that used to serve as channels for storm water have also been encroached.

Shimla, Chamba, Dharamshala, McLeodganj, Solan, Mandi, Manali and Kullu are all guilty of permitting such illegal structures. And as these towns also fall in the category of Seismic Zones IV and V, even a small earthquake can spell doom.

Such constructions by influential people in violation of all rules left the Himachal Pradesh High Court with no option but to order their sealing, disconnection of power and water supplies, apart from demolitions in some cases. But that 2018 order had no tangible outcome. The sealed properties were later allowed to reopen without any consquences.

In 2018, following High Court orders, the Kullu district administration alone detected violations in 200 hotels of which 95 had raised illegal floors. They promoters also included politicians, their relatives and business families, The BJP government on return to power allowed the promoters to run these hotels, just closing down the unauthorised portion/floor. But those too gradually got regularised.

Slow realisation

Top officials say the process of creating a master plan for Shimla is in the works. But little is expected to change. Yet, D C Rana, Director Environment Protection and Climate Change department, claims that “we want all new constructions should have components of climate change.”

What he implies is that the buildings should address structural safety, be energy efficient, have rain water harvesting and adequate fire safety. According to Rana, authorities will soon undertake a fresh vulnerability assessment of the town. The department will also recommend that Town and country Planning (TCP) Act and Urban Local Bodies should have statutory provisions to ensure building plans strictly follow the building codes.

Former Shimla Deputy Mayor Tikender Panwar quotes three recent studies done by the state Disaster Management cell in 2015 on hazard risk, vulnerability assessment, city resilience index and rapid visual survey of the buildings.

“The studies recommended that it was high time all construction should be brought to a halt and adaptation strategies should rather be the focus areas,” says Panwar. “The city requires a master plan for land use, tourism and transport. Structural assessment (safety audit) is must to secure lives in case of a catastrophe due to climate events.”

But all that is in the future. Shimla is already seeing climate change in the form of less/or no snow in the winters and rise in heat during summers. “The Shimla water crisis in 2018 is a grim reminder of playing havoc with its hills and forests in this era of climate change,” says Amarjit Singh, a businessman and real estate promoter. He admits that it is mainly the haphazard growth of the town, lack of planning and greed that led to compromise with urban planning. “Now, addressing the climate change issue is a big challenge.”

Also read:

Superb article……?????

This is such an eye opening article, how overtourism is leading to devastating these ecologically and environmentally sensitive areas. Strict laws and implementation is the real need. We can’t lose innocent lives for someone’s greed.