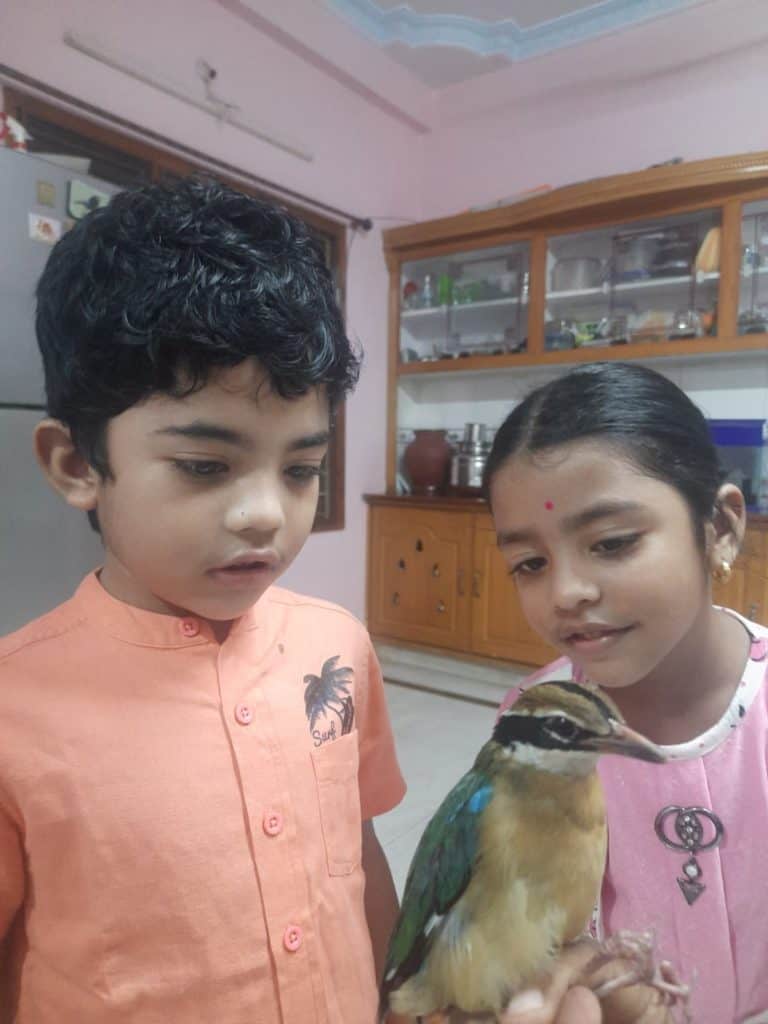

It’s early morning, and the PfA Wildlife Rescue and Conservation Centre in Kengeri receives a call. A small bird with blue, green, and black wings is lying immobile on a terrace, said the caller. The roof, wet from incessant drizzle, is bespeckled with a handful of orange and white down feathers. Feral cats are on the prowl. The caller says he picked up the bird and placed it indoors, in a warm corner. He has no clue what this spectacular, multicoloured bird is, but the rescuer, already racing on his bike, knows only too well. A visiting Indian Pitta.

Now is the season the people of Bengaluru, and its plethora of birdwatchers, await, for entirely different reasons. For the latter, the months from October to December are all about a legion of avian species making their way into the city, adding a kaleidoscope of colour to our concrete landscape.

When the cold sets in and daylight diminishes in north India, and breeding sites suffer a shortage of food, many species start on a long journey south. Apart from the inimitable Indian Pitta, which descends all the way from the foothills of the Himalayas, you can also spot the Grey wagtail, Ashy drongo, Golden oriole, many species of flycatchers, warblers, ducks, sandpipers, plovers, and several other waders. They fly in and take to our parks, open fields, wetlands and the odd semi-open spaces of our homes, malls and offices, absorbing the warmer weather and resources that help them survive.

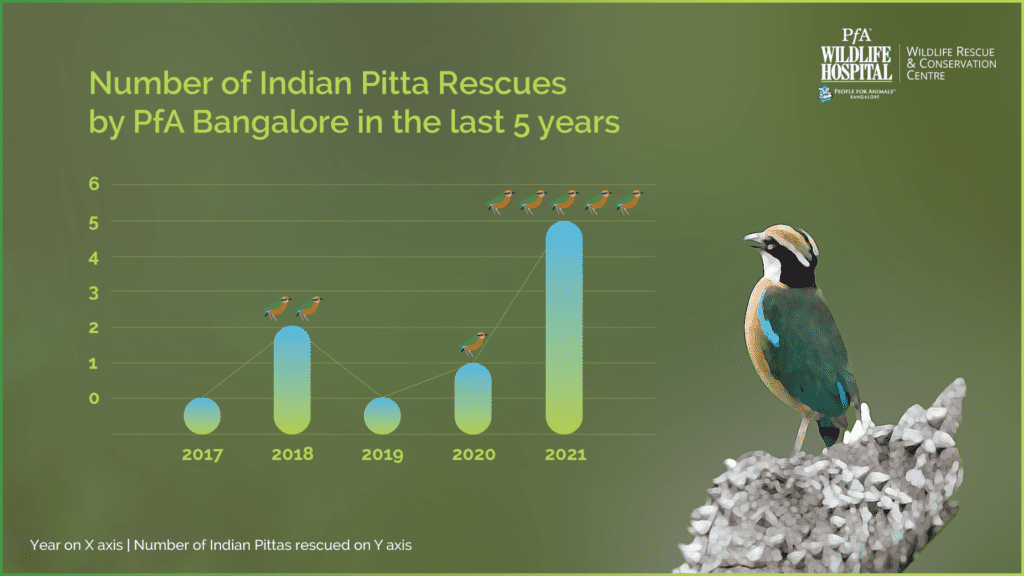

The PfA (People for Animals) Bengaluru centre has rescued 137 species of birds to date, a list that includes common city residents as well as rare visitors. The surprise this year was the sudden inflow of Indian Pittas. Between 2017 and 2020 (in the months of October and November), the centre had to rescue only three Pittas, but the number has risen to five in the last few weeks alone.

Read more: The lake of thousand birds to receive treated water by mid-year

So what’s going wrong, what’s changed?

In general, migratory birds are very vulnerable and unable to adapt to changing urban habitats as abundant vegetation, food and water, along with favourable weather, are not assured. This year, these conditions in Bengaluru have been highly unfavourable, for many reasons.

The city has experienced unexpectedly heavy and incessant rainfall. The first three weeks of November 2021 recorded over 120 mm of rain, almost eight times that of the previous four-year average of 17 mm for the month. And then there are urban development projects all over. Trees have been pulled down en masse, with no regard for the wildlife they support. Gardens are being over-manicured and routinely fumigated, killing insects and affecting nests. Lake water pollution remains a huge concern. Plastic pollution continues, finding a way into the diets of animals large and small.

Real number of Pittas in trouble is much higher

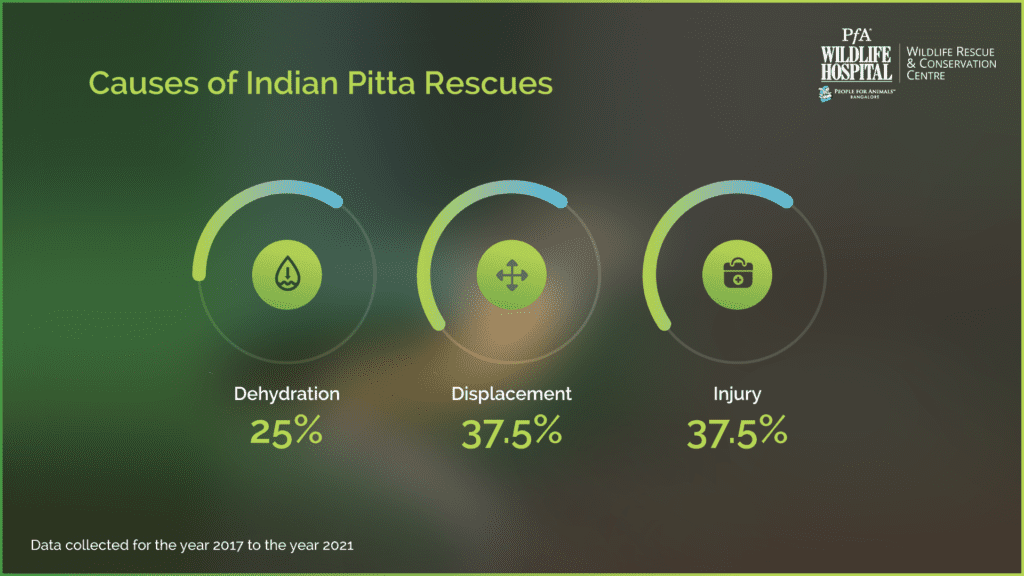

This year, we received calls for Pitta rescues from across the city – Basaveshwaranagar, JP Nagar, Shivajinagar, Ulsoor and Vijayanagar. The most common cause was dehydration. Two birds had wing injuries, which veterinarians dealt with swiftly. All five were successfully released. There’s little doubt that the real quantum of Pittas in trouble is at least 10 times higher.

Easily identified by a black stripe that crosses its eyes on its light brown head, the stubby-tailed Indian Pitta has a plumage which consists of nine vibrant colours (hence the moniker ‘navrang’). Its summer breeding grounds are the plains and foothills of the Himalayas, and its winters are spent in south India and Sri Lanka. It feeds on insects, and has a signature two-noted whistle call.

All birds, including the Indian PItta, are incredibly important to the health of a city. They pollinate our trees and plants, enhance green cover naturally, maintain a balance in the urban ecosystem, and help control the insect vector population. Today, science clearly shows us that more trees means cleaner air, natural temperature and humidity control, better soil fertility and more water retention.

Read more: What we lose when we lose a lake — the Mallathahalli Lake experience

The Indian Pitta is special in more ways than one. It is a beacon for our city’s development, a measure of what our urban ecosystem should and should not allow, given that climate change and poorly-planned urbanisation threatens our future.

Migratory birds, and their notified habitats, are included in Schedule-I of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, giving them the highest degree of protection. But that’s not enough.

Here’s what you can do when you find an injured or immobile bird. If it’s not a wing injury, it’s probably dehydration. Avoid handling it as much as possible, as they are highly prone to stress. Place a shallow bowl of water next to the bird, so it can rehydrate itself. Wrap it in a small towel and ensure it’s safely secured, away from predators. Call for help, on our free rescue helpline on +91 9900025370.

You are doing an excellent job in rescuing birds. May your tribe increase,Amen