The extension of 3rd Cross road in Vijayanagar is like any emerging neighbourhood in Bengaluru, with houses packed like boxes on either side. This led us to explore the role of regulations in shaping our buildings, streets and city at large. We presented our findings at the ‘Bengaluru Design Jam’, organised by organised by OpenCity, and held on July 6th. The participants collaborated to analyse and interpret different aspects of BBMP’s construction bye-laws.

The changes and growth of cities are often guided by economic activities. But the development of cities needs to be managed and regulated to ensure liveability. This is where master plans and zoning regulations come in, much along the lines of what has been practised in developed countries.

What is a master plan?

A master plan is a comprehensive mid to long-term plan that outlines how a city will grow spatially, and the various alternative uses for different sections of the land. Zoning regulations specify what can be built, how, and the permitted uses of built up structures in identified ‘zones’ or parcels of land.

How a city responds to these regulations can differ. In a rapidly growing city like Bengaluru, it is important to ask if such regulations are conducive to and compatible with the growth of the city. Or, should there be a separate mechanism to adapt to the needs of the growing city?

Read more: Non-existent roads make it to Bengaluru master plan

Study area

At the datajam, our team tried to find answers to the above questions by examining the built-up fabric in the south-western part of Bengaluru. We chose the neighbourhood of Vijayanagar, which is less than 6 kms from the city centre. The study area was about 500 metres from Chord Road, one of the important arterial roads of the city.

Methodology

We looked at typical streets with residential land use, which have plots of sizes 600 sqft (20’X30”), 1,200sqft (30’X40’), 2,400 sqft (60’X40’). One street adjoining the neighbourhood, which had commercial land use, was also considered. These streets identified were then examined through Google Street view images.

The parameters we were looking at were land use, setbacks, site coverage, total built-up area, building height.The objective was to look at whether these parameters conformed to the zoning regulations under the city Masterplan 2015.

Read more: Revised Master Plan-2031: Revisions only – neither mastery nor planning?

Observation and analysis

The study analyses the built-up forms through the lens of the identified parameters for all the street types mentioned above. The observations made are then interpreted through the analysis matrix below.

Building height and Floor Area Ratio (FAR) regulation in streets with commercial land use are the same as in the adjoining residential areas, which restricts potential development. Also, there are no specific regulations for car parking on commercial land use streets, which is important to consider.

Analysis matrix

| Plot Size | 20×30 (6.5m*9m) | 30×40 (9m*12m) | 40×60 (12m*18m) | Commercial Street |

| Street width | 7m | 9m | 12m | 9m |

| Permissible Land Use | Residential | Residential | Residential | Commercial |

| Condition observed | Conform | Conform | Do not conform | Do not conform |

| Permissible Setback | Left 0m, All other sides 1m. | 1m on all sides | 1m on Rear, 1.5m Sides | 1m on Rear, 1.5m Sides |

| Condition observed | Do not conform | Do not conform | Do not conform | Do not conform |

| Permissible Coverage | 75% (31.5 sqm) | 75% (81 sqm) | 75% (162 sqm) | 75% |

| Permissible Floor Area Ratio | 1.75 | 1.75 | 1.75 | 1.75 |

| Approx. permissible area | 102.375 sqm | 187 sqm | 378 sqm | 378 sqm |

| Condition observed | Do not conform | Do not conform | Do not conform | Do not conform |

| Building Height | 15m | 15m | 15m | 15m |

| Condition observed | Do not conform | Do not conform | Do not conform | Do not conform |

The above analysis shows that there is predominant violation of regulations with respect to building floor area, setbacks, building height especially with respect to smaller plots. In larger plots, commercial use is observed even in residential plots.

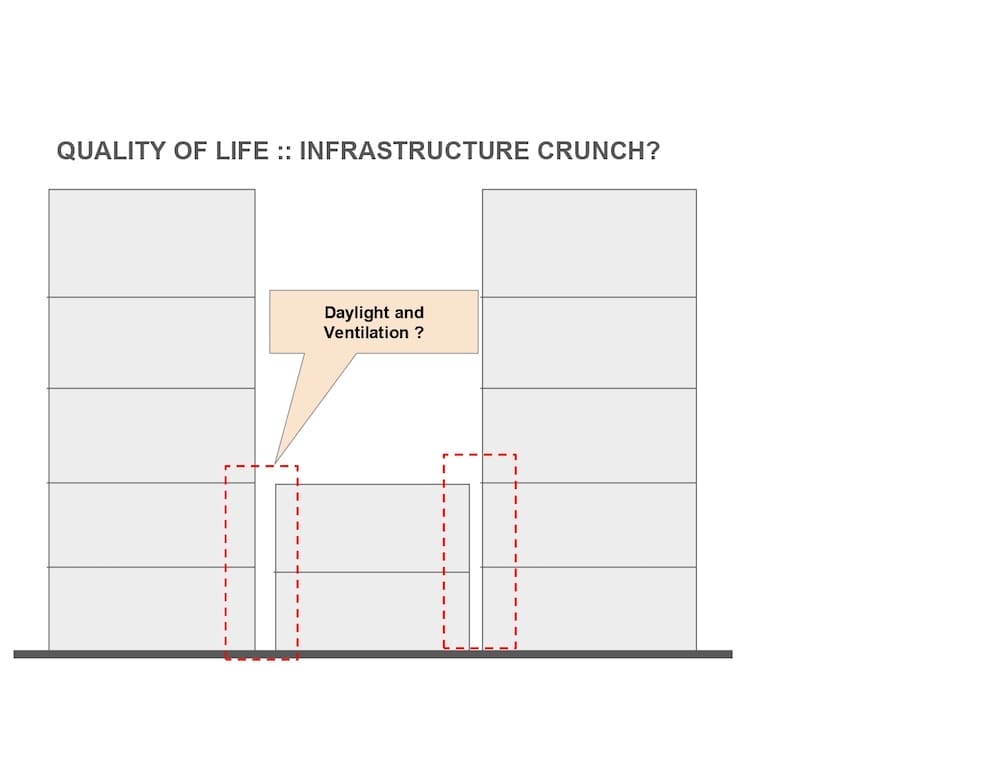

The reduction in setbacks has a direct impact on the quality of light during the day and ventilation in these units. This affects the quality of life of residents living in these residential units. Hence, not conforming to the regulations can be detrimental to the well-being of the population.

Further, there was violation in built-up areas in newer buildings in large plots (>60ftx40ft).

Commercial land use has the same FAR as the adjoining residential land use. The parking spaces have been converted into office/shops to maximise floor space, and this, in turn, results in increasing street parking. The street character, determined by the design of its buildings, is deduced from the nature of buildings that adjoin them.

Rampant parking on streets and unplanned public utilities/street furniture, such as seaters, benches, waste receptacles etc., impact the street quality and make them less pedestrian friendly. This further increases motorised traffic, thus increasing the vehicular density, and resulting in higher pollution levels.

Hence, it is largely observed that the regulations are not being followed in the construction of buildings on individual plots, where the homeowners maximise the use of space available for building. This is driven by demand for floor space and the high land value in the area. It is economics that is driving the city‘s form, rather than regulations.

Conclusion

Deeper deliberation is required to formulate relevant regulations to manage the growth of the city. Lack of enforcement is a primary reason for people being lax about following the regulations.

Most regulations are laid out as blanket rules, which may not be relevant for the diverse conditions of the city. Regulations shall be specific to zones and the type of land use. For example, the FAR of 1.75 and coverage of 75% for a wide range of plot sizes conforming to the street width in different parts of the city may not be the best way to regulate growth. The contextual conditions may be different for different streets and neighbourhoods. This evidently shows lack of micro-level planning and dynamic response to city growth. Micro-level planning / Local Area plans need to be prepared for the city after consultations with local stakeholders.

Adapting regulations dynamically in response to economics would also promote sustainable city growth.

Addressing violations through relevant support regulations and effective enforcement is crucial in regulating city growth; otherwise the regulations merely remain on paper, contributing very little to the development of the city.