This article is part of our special series Environmental Sustainability & Climate Change in Tier II cities supported by Climate Trends.

Situated on the banks of river Ganga, Varanasi, India’s holiest city and the constituency of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, came into limelight in 2015, when Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) data highlighted that the city didn’t have even a single good air quality day that year. In fact, Varanasi is among the 43 critically polluted zones across the country. Not just air, its water quality is equally pathetic.

Pollution indices in Varanasi have only got worse with time. In 2017, CPCB called it the most polluted city in the country, while in 2018, WHO listed it as the 3rd most polluted city in the world. Data revealed that pollution levels in Varanasi were 20 times more than WHO’s standards. In fact, the city’s air quality was found to be more toxic than in Delhi. Though in that year the city reported seven days of good air quality, as compared to zero in 2015.

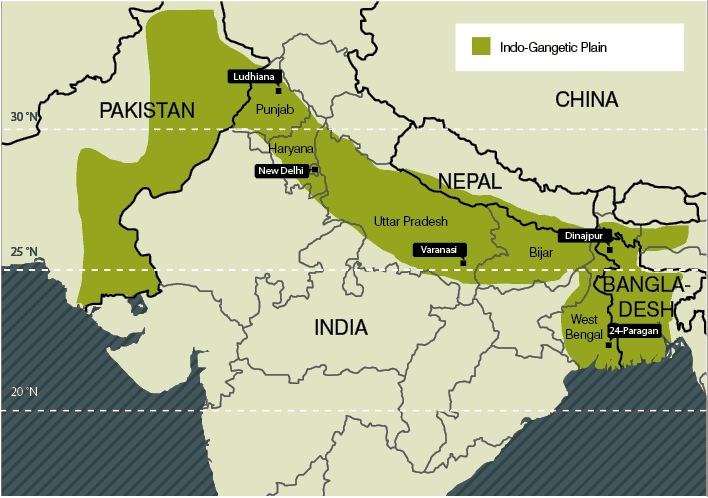

The bad news, however, is not restricted to this one city situated in India’s most strategic and sensitive ecosystem, the Indo-Gangetic Plain (IGP). The plain harbours almost 40% of the country’s population, making it one of the most densely populated ecosystems in the world.

Which has also made it the country’s most polluted region in terms of air and water quality. In an October 2020 survey of 54 cities in the Indo-Gangetic Plain, the CPCB found half of them reporting ‘poor’ or ‘very poor’ air quality. Vehicular emission, industrial pollution and dust are cited as the major causes of pollution as per CPCB’s analysis.

A fact reflected in just about every other study. IQ Air, an Air Quality information platform, releases a list of world’s most polluted cities every year. As per its 2019 index, out of top 30 polluted cities, 21 were from India. More importantly, all 21 of these cities are from IGP with a majority of them from Haryana and Uttar Pradesh. With cities like Kanpur, Agra and Varanasi polluted not only in terms of its air quality but also in terms of pathetic water quality. Not surprisingly, all these cities find a place in India’s critically polluted zones.

In fact, a Climate Trend funded report by India Spend singles out Varanasi as among cities with the worst air quality.

And the effects of the air crisis have been disastrous. One of the most alarming research shared by the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago (EPIC) in 2019 was that people residing in IGP are losing 7.5 years due to air pollution. The study noted that pollution levels have increased by 72% from 1998 to 2016.

Shockingly, as per the State of Global Air 2020 report, around 1.6 lakh infants died within the first year of their birth in 2019 in India. The report stated that these deaths were caused due to PM 2.5 in outdoors as well as indoor due to burning of solid fuel (like wood, animal dung, charcoal etc.). PM 2.5 was also responsible for causing 9,80,000 deaths due to air pollution in India.

Separating the peninsular plateau from the Himalayas, IGP spans four countries, India, Nepal, Bangladesh and Pakistan, stretching from Rajasthan to Assam within our country. And in today’s era of climate change and global warming, like several other ecosystems, IGP too is facing serious ecological challenges. From threatened river basins to rising air pollution, IGP is rapidly becoming the hotspot of climate change in the country. Moreover, increasing urbanization and human activities are putting extra pressure on the sensitive ecosystem.

Poor air quality alone is having disastrous effects on agriculture and public health as reflected in the research shared by the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago (EPIC) in 2019. Their research revealed that people residing in IGP are losing 7.5 years due to air pollution. The study noted that pollution levels have increased by 72% from 1998 to 2016.

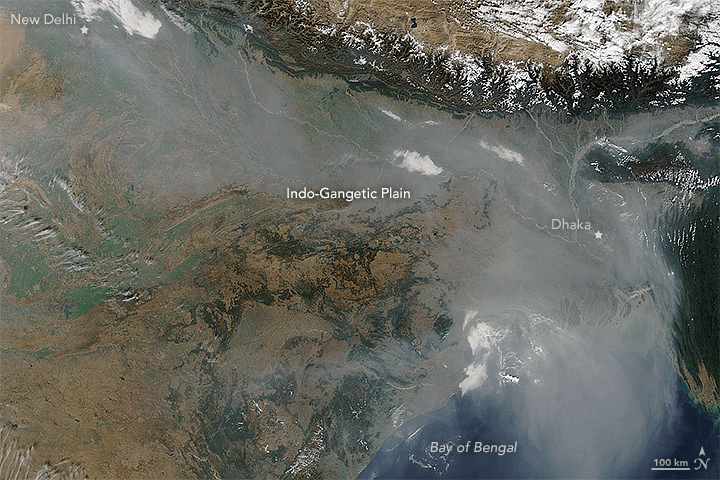

Air pollution has, for years now, been a recurring problem in the IGP. The emissions from IGP have been contributing massively to the airshed – a geographical area sharing common flow of air. “Air pollution in the Indo-Gangetic plains is a complex phenomenon dependent on a variety of factors,” says Dr. Pallav Purohit, a researcher at International Institute For Applied Systems Analysis (renowned global research organization on air pollution), Austria.

Plans aplenty, implementation zero

Varanasi’s condition is typical of factors contributing to air pollution on the entire IGP area. As per the clean air plan prepared by Uttar Pradesh Pollution Control Board, road dust (92%), vehicular emissions (2%), burning of solid fuels in households (3%), garbage burning (2%) and agriculture waste burning (2%) were identified as primary sources of air pollution in the city, besides industrial pollution, use of diesel generator sets and brick kilns.

“The Indo-Gangetic plain is essentially landlocked,” explains Dr. Purohit. “The Himalayas prevent polluted air from escaping to the north creating the so-called ‘valley effect’—the formation of low-pressure troughs across the region which causes winds to converge, resulting in trapping of local, as well as pollution from outside”.

For Varanasi, the government has drawn up an action plan which lists a number of short and long term activities to curb pollution like introducing electric buses and establishing charging stations, construction of ring roads and peripheral roads to avoid congestion in the city, creating multilevel parking facilities, creating cycling zones, using bio-ethanol in the city, installing waste to energy facilities etc.

But successful implementation of these measures look grim. For instance, the city has had only one online air quality monitoring system that measures both PM 2.5 and PM 10 levels. In November 2020, the government decided to install 10 new monitoring stations in the state, out of which three will be deployed in Varanasi. However there is no firm date by when this will happen.

The state government cleared the project for rolling out around 40 electric buses across various cities, including Varanasi. But these cities still lack the requisite infrastructure to facilitate the operation of the electric buses. The crunch in funding remains the major obstacle.

Waste burning and road dust continues to deteriorate the city’s air quality, as it was noted in the recent data collection drive by a local group.

Varanasi also struggles without a modern high speed public transport system. After dismissing a metro rail option, in 2019, Rail India Technical and Economic Service (RITES) has proposed to a light metro rail service at a cost of Rs. 17.7 crore.

Varanasi’s dense urban structure is again typical of the ills that face other IGP cities. “Pollution levels in IGP is higher because of its dense nature of everything – population, trade, industries, and the associated emissions from sectors such as transport, industries, waste burning, cooking and heating, and dust”, explains Dr. Sarath Guttikunda, Director, Urban Emissions, a research group engaged in science and data based analysis of air pollution in India.

Impact on agriculture

Uttar Pradesh is the largest state in IGP – having a population of more than 200 million. Rapid and unplanned urbanization, rampant industrialization and high population density have made cities of Uttar Pradesh, the front runners in terms of air pollution. Therefore, the scope of air pollution is not only limited to big metropolitan cities but is rapidly encompassing small cities too. Further, UP, Haryana and Delhi together host around 10% of the total thermal power plants in the country, making IGP more vulnerable to air pollution.

A study at the University of California, San Diego, had highlighted the impact of air pollution on agriculture in the IGP-based states and how rainfall levels and temperature patterns have been impacted. For example, UP, a major wheat producing state in IGP witnessed a wheat yield loss of almost 19%, translating into a financial loss of $5 billion. Similar implications have been observed for rice producing states in the northern plains.

Surprisingly, studies show that stubble burning, which Delhi makes a huge fuss about every winter as the main cause of the capital’s poor air quality, is not the main cause of high pollution levels in the IGP. One study conducted in six IGP cities (Delhi, Jaipur, Lucknow, Kanpur, Varanasi and Patna) makes a striking remark that reduction in biomass burning, including stubble burning, will have a smaller effect on reducing air pollution as compared to reduction in anthropogenic emissions.

Therefore, the focus of mitigation measures should be on anthropogenic emissions, specifically on household energy usage, such as promoting use of clean cooking fuels, say experts. “A focus on the reduction of primary PM 2.5 (e.g. tightening emission norms for vehicles and power plants) will only address half the problem,” says Dr. Purohit. “A significant share of emissions still originates from sources associated with poverty and underdevelopment such as solid fuel use in households and poor waste management practices”.

Unscientific response

Unfortunately, In India, discussion and response on air pollution has been episodic and piecemeal. It gets attention only when air quality reaches very poor in Delhi-NCR and other cities, especially during October-November. Experts say blaming this on stubble burning by farmers in Punjab and Haryana is an “over simplification” of the issue and also a “myth”.

“We have year round sources of air pollution, which need attention and these include any sector that burns petrol, diesel, gas, waste, and coal, and dust on the roads and from construction activities,” says Dr. Sarath. An argument that Dr. Purohit echoes as well.

Official response also often ignores the principles of science and logic. For instance, the installation of smog towers in Delhi, each of which costs Rs 10 crore and takes 10 months to come up. But going by scientific analysis and expert comments, installing smog towers is not a good idea at all. “It is unscientific to assume that one can trap air, clean it, and release into the same atmosphere simultaneously,” writes Dr. Sarath in his recent paper Can we vacuum our air pollution problem using smog towers?

Also read: