Good mobility relies on a number of measures – urban planning, transportation planning and traffic flow control. This section explores various measures related to urban planning.

This multi-part series examines the measures needed to sustain and improve urban mobility. For a detailed discussion on each measure, check the following guides:

Part 1: Urban planning measures (this article)

Part 2: Transportation planning measures

Part 3: Traffic control measures

Also see: An action agenda for better mobility

The article How to make Bengaluru traffic jams go away analyses these measures in the context of Bengaluru.

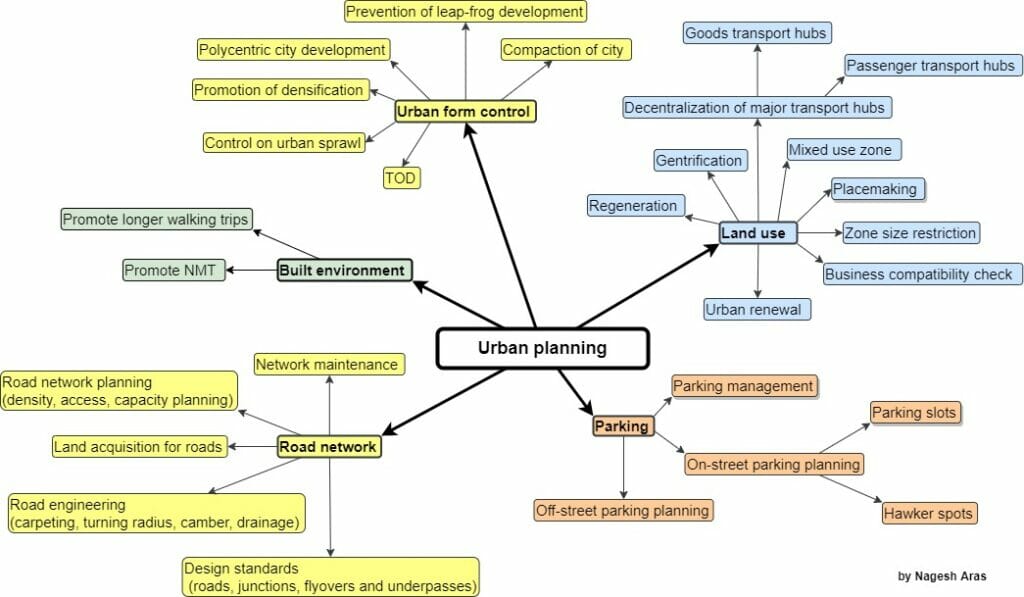

Half the battle is won when a city is well-planned to carry its traffic. City planners must take measures that control and change the shape of the city itself, by controlling the urban form, land use and design of individual neighbourhoods. Typically, such urban planning and measures span a very large area (citywide in most cases), and require very large budgets. They are implemented over a very long period.

In some cases, the present-day buildings cannot be demolished to implement the proposed project, and so a long-term futuristic plan is made, which is meant to be implemented after a couple of decades, when the area would become ripe for regeneration.

Urban form control includes compaction of the city (where building outside the core city is discouraged) and densification (in which low-rise housing is discouraged and high-rise buildings are encouraged). Control over land use ensures that workplaces and residential zones are evenly distributed across the city so that the city does not experience asymmetrical traffic rush.

Measures are also taken to ensure that the city has adequate roads to accommodate our vehicles, and a grid of roads, so that when any given road has congestion, people can find alternative routes easily.

Proper infrastructure is created to encourage people to walk or use bicycles for local trips. Localities are designed to encourage community cultural/sports activities in public spaces, which also encourage people to avoid motorised transportation.

Finally, on-street parking is controlled to ensure that roads remain obstacle-free. Parking availability is restricted to deliberately nudge people to use public transport.

I. Urban form control

The term “urban form” is used to describe a city’s physical characteristics. It refers to the size, shape and configuration of an urban area or its parts. The planners must control the shape and growth of the city through the following measures:

Polycentric city development

In this “cities within a city’ approach, each urban area is designed to be self-sufficient, to reduce travel needs. Typically, the urban planners divide the city in sectors or zones, and make it mandatory that each sector/zone must have all basic amenities, such as grocers, primary school, primary health centre, etc. Gandhinagar in Gujarat is a good example.

Urban sprawl

Urban sprawl is the proliferation of low-rise houses. When the population is thinly spread out over a vast area, it is too expensive to provide public transport to such areas. So people have to use their own vehicles. This causes congestion on the roads. That is why it is important to curb urban sprawl.

Compact city

Planners must aim to create a compact city by discouraging development on the outskirts of the city. A compact city has dense and proximate development patterns linked by public transport systems and with accessibility to local services and jobs. This results in lower infrastructure costs and higher energy and resource efficiency. It also maximises the economic, social and environmental potential of the city.

Densification

The population density of a city has a direct impact on the quality of life and sustainability. When a large number of the population lives in a small area, providing public transport becomes simpler and cheaper. When most people adopt public transport, the congestion on the roads is drastically reduced. Hence the planners must encourage the densification of urban population.

Leapfrog development

The land in the city is costly, and many people cannot afford to buy homes. But land outside the city limits is much cheaper. Builders take advantage of such cheap land and develop properties there. Some builders prefer to build outside city limits because large tracts of land are not available inside city limits. This is called “leapfrog development”.

Many people are lured by cheap housing. But such outflung areas don’t have public transport, and so people living in city outskirts have to commute to the city using their personal vehicles. This causes congestion in the city. Therefore leapfrog development must be discouraged.

Transit-Oriented Development (TOD)

This is an approach in which a mix of commercial, residential, office and entertainment properties are centred around or located near a transit station. This creates densely populated self-contained neighbourhoods that promote walking and biking instead of driving.

Read more: To develop a city for transit, or transit for a city?

II. Land use

The traffic in the city depends on how the urban land is used, because each different type of use creates a different pattern of traffic.

For example, compare the traffic generated by a residential complex, an office complex, a mall and a cloud kitchen:

- Residential complexes: People leave for work/study in the morning and return at night.

- Office complex: People come to work in the morning, and leave in the evening.

- Mall: People come and leave throughout the day. If the mall has a multiplex, a large number of people arrive and leave together for different shows.

- Cloud kitchen: A large number of delivery agents remain parked near it, and leave for delivery trips. The number of trips peaks during lunch and dinner time.

Therefore the urban planners must try to change the urban form in order to control traffic patterns in the city.

Mixed-use zones

If a city has large areas (“zones”) that are of a single type (residential, commercial, educational or shopping), it generates a large number of trips in one direction. For example, every person in a residential zone would leave for work. This overloads public transport in one direction. If the zones are created for mixed use, the commuters would travel in different directions at any given time, and thus the public transportation system would not be overloaded in a single direction.

Restriction on the zone size

The urban planners must not let any particular type of zone to grow very large, because it creates traffic imbalance. If smaller zones of different types are adjacent to each other, the traffic in all directions remains nearly uniform.

Regeneration policy

It is difficult to change the urban form of a city area that is already developed. For example, it is not possible to break down a giant software tech park into smaller parks interspersed by residential zones. But this opportunity comes when the buildings in an area grow old, are demolished and replaced with new structures. At this time, the urban planners must apply an urban regeneration policy. This enforces a change of the urban form.

Gentrification

There is a similar urban process called gentrification, in which low-income housing in the city is replaced with more “up-market” housing or commercial complexes. This is a very gradual transformation, and happens over a few decades. This also presents an opportunity to the urban planners to force a change of land use.

Urban renewal

Sometimes the government acquires an entire area and plans new development, including making wider roads, setting up public infrastructure, etc. This is called urban renewal.

Decentralised transport hubs

Most cities have a legacy issue: massive centralised transport hubs. These hubs may be for passengers (e.g. bus terminus) or goods transport (e.g. city market).

If these traffic hubs are located inside a city, a lot of outside vehicles enter the city, and park for a long duration. This causes congestion in the city. This congestion can be eliminated by (a) splitting major hubs to serve different parts of the city, (b) moving the parts to the outskirts of the city and (c) connecting the new hubs to the city with rapid transit system.

Compatibility check for businesses

Every business has a typical traffic pattern. For example, for an office complex, workers commute from their homes using cars, two-wheelers or public transport. A cloud kitchen attracts a large number of delivery agents on two-wheelers. All customers of an upscale restaurant would be car-users. All businesses get their supplies in delivery vans.

All this creates a demand for parking and road space. But any given locality has limited parking space and road space. Therefore it can accommodate only a limited number of businesses of specific type. This requires a tight control on what type of land uses are allowed in each zone. Before issuing a licence to any business, its impact on the parking and traffic must be assessed.

III. Built Environment

The built environment can be described as the human-made space in which people live, work and recreate on a day-to-day basis. This has the third-largest impact on traffic, after urban form and land use.

Non Motorised Transport

Non-motorised transport (NMT) includes modes such as walking, bicycling, skating, skateboarding, push scooters, hand carts, wheelchair travel, etc. It is also known as “Active mobility” and “Active travel”. NMT not only reduces air pollution, but also makes people healthier through daily exercise. Therefore, while designing new public infrastructure, the urban planner is expected to promote NMT.

Read more: No rights, no dignity, no safety for Delhi cyclists, only the “tyranny of motorists”

Placemaking

A placemaking project creates public spaces that promote people’s health, happiness, and well-being. This includes planning, creation and management of such public places.

IV. Road network

Except for the metro and railways, all other vehicles ply on roads. Therefore the road network must be able to accommodate all types of vehicles in large numbers.

Road density

Every part of the city needs a certain minimum road density to carry the projected vehicular and pedestrian traffic. (Road density is measured in terms of km of road per unit area.) In addition, the roads must be interconnected to form a grid, so that people can avoid congestion by taking alternative routes.

Land acquisition

The urban planners must plan the road network in any new area in such a way that the required road density is achieved. For this purpose, they must acquire land in advance before anyone has a chance to develop properties on such land.

Compliance with engineering standards

All features of the roads must comply with engineering standards (e.g. carpet, turning radius, camber, drainage).

All parts of the road network (roads, junctions, flyovers and underpasses) must comply with standards, to make them safe and efficient.

Read more: Road maintenance: What BBMP does not track

Note that roads are the only public open spaces that can be used to lay down essential utility supply lines: water, sewerage, electricity, gas, TV, internet, etc. Note also that these utilities often require adequate safety margins. For example, power lines and gas lines cannot be laid in close proximity. Similarly, water pipelines and sewerage are never laid together. This imposes additional engineering challenges for the roads.

The capacity of the road network must be preserved by regular maintenance and removal of encroachments.

V. Parking

Many people assume that free parking on the road is their right. In addition, hawkers occupy space on roads and footpaths. The combined effect is a drastic loss of capacity of the road and footpath, which leads to congestion.

Traditionally, a parking policy tries to meet the demand for parking slots, and does not deal with the space occupied by hawkers. Such a policy will fail to achieve its dual objectives of (a) restoring the full capacity of the roads and footpaths, and (b) nudging people to use public transport.

Therefore, parking policy and strategy must allow on-street parking and hawking only if the target capacities of the road and footpath are met first. Also, it must make parking scarce and keep the parking charges high, so that people are nudged toward public transport.

Read more: Is Mumbai a step closer to solving its parking crisis?

A new challenge in recent times (especially post-pandemic) has risen: Many new online businesses have developed to supply cooked food and grocery to your doorstep. Further, due to intense competition, these businesses have started committing very short delivery times. This means that they cannot wait to aggregate their orders from one locality, but have to serve each individual order separately.

As a result, the number of delivery trips has exploded. This large number of trips creates a shortage of parking space, because the delivery agents desperately crowd the supply points to pick up their package and then they have to park their vehicle at the customer’s premises. Typically, parking at both ends of the trip is not adequate. As a result, they end up parking on footpaths or roads, creating a blockage.

The solution may be to issue licences to such businesses only when their transportation needs are compatible with the available infrastructure in the area. We also may have to introduce a new regulation so that the residential complexes are forced to allocate off-street parking space to the delivery agents.