For Ghulam Ahmed Mir, owner of a provision store on Residency Road, Lal Chowk, pulling up the shutters of his shop on June 14th, was like a dream come true.

But tears filled Mir’s eyes as soon as he stepped into his shop for the first time in 85 days. Rats and insects had wreaked havoc inside. Packets of biscuits, chocolates, coconut, atta, dry fruit and other grocery items were strewn on the floor. “The rats and insects have tasted everything and wasted everything for me,” said a tearful Mir.

As the clock struck 9 on the morning on June 14th, Lal Chowk, Srinagar’s central business hub reverberated with the noise of shop shutters opening after an 85-day lockdown. The city of 1.5 million had been in total lockdown since March 18th, when the first case of Covid-19 was reported from old Srinagar.

The opening came after hectic deliberations between traders and the Srinagar district administration, where everyone agreed that it was time to open the markets. At a final meeting on June 13th, it was decided that markets would be opened the next day, with strict implementation of Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) on maintaining social distancing and other health precautions.

The opening was particularly welcome, given that the lockdown happened just as business activities had started picking up in the first two weeks of March after almost seven months of uncertainty triggered by last year’s roll back of article 370 and the conversion of erstwhile J&K state into two Union Territories (UTs)—Ladakh and J&K. It was an emotional moment for business owners and people, even though shops did little business that day.

Mir lives in Hyderpora area of Srinagar’s civil lines and his shop is the primary source of income for his family of four—wife and three children, two of whom are studying abroad. Owning a shop in the heart of Lal Chowk was in itself a big achievement for him, shared Mir as he got down to cleaning up the half-eaten biscuits and nuts from the shelves and removing the thick cover of dust that covered the grocery bags.

In his 60s now, Mir, by his own account, has lost over Rs 15 lakh since the lockdown was imposed. “On a normal day, I would sell grocery items worth Rs 20,000 to 30,000. We were already incurring losses due to last year’s six- month long lockdown triggered by abrogation of article 370”.

The historic chowk

Lal Chowk, also called Red Square, played an important role in the recent history of Srinagar. It was named Lal Chowk by left-wing activists who were against former Dogra ruler of Kashmir Maharaja Hari Singh. It used to be a traditional place for political meetings and rallies for Jawaharlal Nehru and the erstwhile Jammu & Kashmir State’s first Prime Minister Sheikh Muhammad Abdullah. It was where Pandit Nehru unfurled the tricolour and addressed a rally in 1948 promising the people of Kashmir plebiscite to choose their future.

Many prominent leaders have addressed people in Lal Chowk. The clock tower in the middle of Lal Chowk, constructed by Bajaj electricals as part of their advertisement campaign, gained political significance in 1992 when the then Bhartiya Janata Party leader Muri Manohar Joshi came to hoist the national flag atop the tower on Republic Day. Despite militant threats, Joshi managed to unfurl the tricolour in presence of security forces personnel. The clock tower has been renovated many a times by past regimes.

Lal Chowk is a combination of small and big markets where a person can get anything of his/her choice. Prior to partition, people would board horse carts and small vehicles to travel to Mirpur and Muzafarabad (then united Kashmir, now part of Pakistan occupied Kashmir) for trade and other business related activities.

In Lal Chowk, a few old shops still exist, besides some historic structures from the Maharajas’ time that includes a Gurudwara and an Ashram-cum-Temple where Amarnath Yatra pilgrims stayed for the night, before proceeding on the pilgrimage. The weekly Sunday market (Flea market) would add to the beauty of Lal Chowk every Sunday with people crowding the market in search of bargains.

All that is history now. Mir is not alone in counting the losses suffered in the past 10 months. Except for a few that include shops selling vehicle spare parts, electric appliances and the watch houses, almost every shopkeeper has a similar tale of loss to share.

Those who faced the maximum brunt of the pandemic lockdown were dry-fruit sellers, medical shops, fruit sellers, readymade garment shops, and booksellers. Most shopkeepers had only one prayer during the trying times: “Oh god, we are on the verge of starvation, first article 370 and now COVID. Forgive us now, don’t show us worse than this.”

Khazir Muhammad, a senior citizen and prominent dry-fruit seller in Lal Chowk, spent the first day drawing circles outside his shop with white paint to ensure social distancing among his customers. Since Kashmiri dry-fruit has a short life and needs to be checked every day, Khazir Muhammad said 70 per cent of his stock had been damaged by insects.

“In March, I had put fresh stock on the shelves that included almonds, dates, dried-plum, coconut, gift packs used for marriage purpose, pure saffron and much more,” said Khazir. “The things I sell are very fragile and need daily care. These products now have to be thrown out. The pandemic has not only ruined our lives but our economy too.”

“We are on the verge of starvation, first article 370 and now COVID. Forgive us now, don’t show us worse than this.”

As Khazir was cleaning the shelves of his shop with, a woman from Abi-Guzar area, a locality close to Lal Chowk, asks him: “Khazir seba, ye kyah soure gomut kharaab, mei ous badaam kilo zorath (Khazir sab, all items have perished, I wanted one kg quality almonds.) “Come after two or three days, I will be getting fresh supply,” Khazir told the woman.

The long wait for customers continues, as shops open in Srinagar after an 85-day lockdown. Pic Shah Jehangir

The joy of shopping after being locked down for 85 days. Pic: Shah Jahangir

Back to business in Lal Chowk, hopefully. Pic: Shah Jehangir

All cleaned up and back to work. Pic: Shah Jahangir

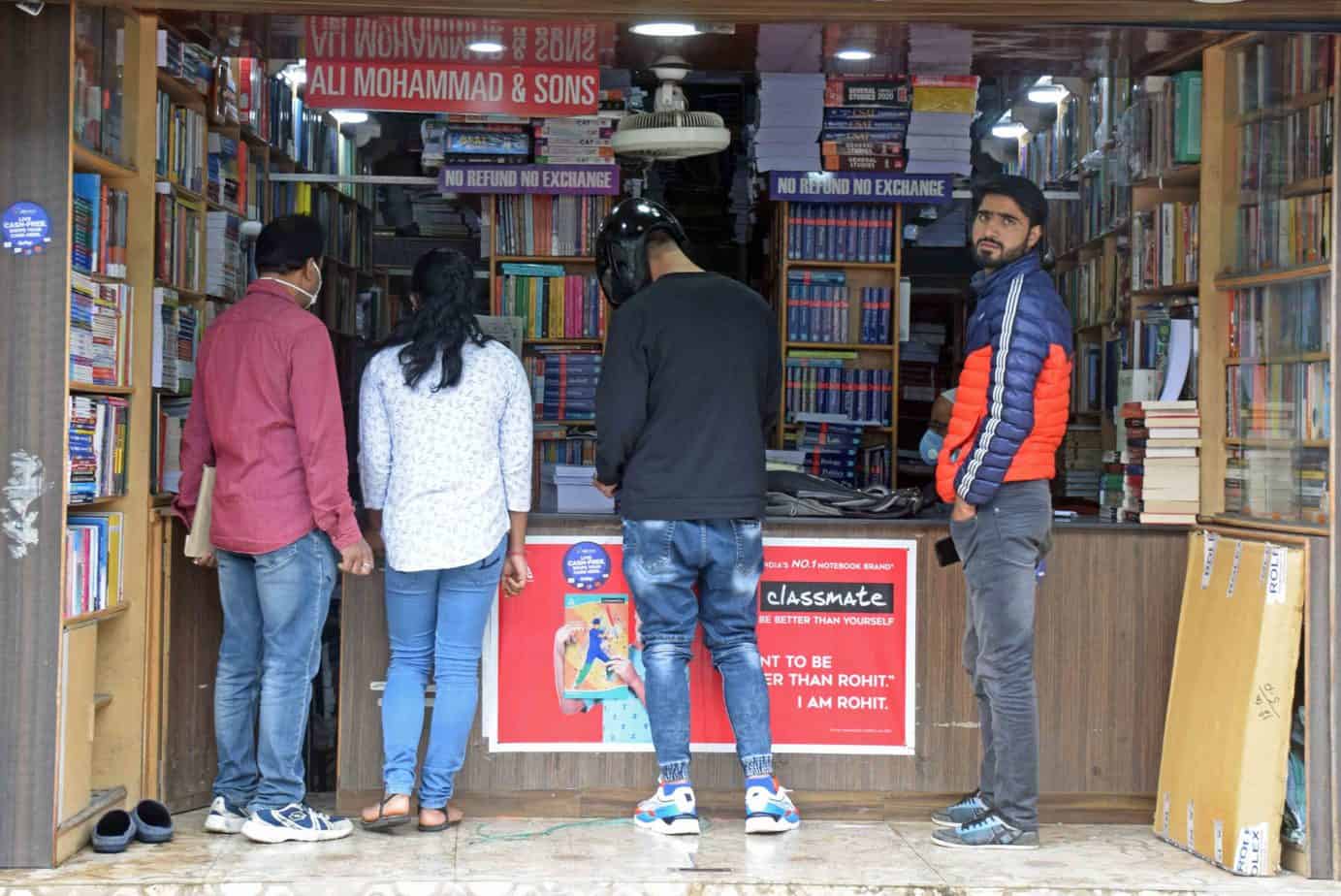

At a book store. Pic: Shah Jahangir

Adjusting to the new normal

Srinagar city has over 4000 shops in 400 markets including the traditional markets of old Srinagar. Showkat Ahmed, a young man who owns a bakery in Zafran Colony in Srinagar’s outskirts, too broke down as he pulled up the shutter of his shop on June 14th. “All bakery items—pastries, cakes, and ice-cream varieties had rotted,” said Showkat, who was using a vacuum cleaner to clear the dust of the shelves. “The first sight of my shop left me heart broken.”

Showkat had over 200 bookings worth Rs 3 lakh for marriage items in April that included gift packs, pastries and cakes etc as the fasting month was scheduled for May. “Since all marriages were cancelled or either held with complete austerity, all my orders were cancelled. It took me almost four days to clean my shop of the dust and rotten items. Tentative loss I have suffered in the past three months is between Rs 10 to 12 lakh.”

The Srinagar district administration headed by Deputy Commissioner Shahid Iqbal Choudhary had sought a written undertaking from traders that SOPs will be followed in letter and spirit. “The primary SOP requirement is to wear masks and not to entertain any customer who comes without a face mask,” said Kashmir Traders and Manufacturers Federation (KTMF) chairman Muhammad Yaseen Khan.

Secondly, traders are supposed to ensure social distancing and not allow customer rush at their shops. “We are ensuring that there is no jumbling or crowd outside our shops. We are letting in customers one by one. A written copy of SOPs has been circulated among all the market heads for strict implementation. I am glad there is no complaint from any market so far,” Yaseen Khan said.

The SOP includes a clause saying any shopkeeper found to violate the protocol will be fined and the licence of the shop seized. The district administration in Srinagar has constituted different teams for SOP monitoring in markets in Srinagar district. “It’s been almost a week now since markets re-opened in Srinagar, but no major complaint of SOP violation has come,” said an administration official.

Now, almost two weeks on, Srinagar markets are abuzz with people thronging the markets and business is gradually starting to pick up. “The shadow left by August 5 last year, however, is still there,” said Imtiyaz Ahmed, who sells electronic gadgets in Lal Chowk. “Customers are fewer, but things are slowly getting back on track.”