The Karnataka government has introduced fresh amendments to the Karnataka Tank Conservation and Development Authority (KTCDA) Act, which could reduce buffer zones around lakes and drains to as little as 0–30 metres. On paper, this may appear to be an administrative change. In reality, it risks accelerating floods, pollution, and water insecurity across Bengaluru.

Here’s what citizens need to know.

How we got here

Bengaluru’s lakes have long been central to the city’s ecology and culture. Recognising their importance, courts and planners have repeatedly mandated protective buffer zones:

- 2012: Karnataka High Court directed a 30-metre buffer around lakes and a 50-metre buffer for primary drains.

- 2015: Revised Master Plan (RMP–2015) included statutory buffers: 30 metres (lakes), 50 metres (primary drains), 25 metres (secondary), 15 metres (tertiary).

- 2016: The National Green Tribunal expanded buffers up to 75 metres for lakes.

- 2019: The Supreme Court set aside the NGT expansion but restored RMP–2015 norms.

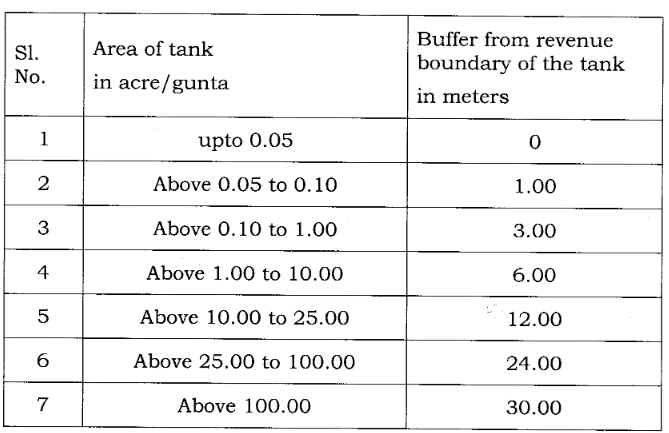

Despite these safeguards, encroachments and sewage inflows continued. Instead of enforcing protections, the government amended the law in 2018 to reduce buffers (as low as nine metres for small lakes). Now, the new amendment proposes an even sharper dilution.

What is being proposed

The proposed KTCDA amendment would allow construction and infrastructure projects to come right up to the edge of lakes and drains, leaving only token strips of land. For small neighbourhood lakes, this could mean buffers of just three metres—no more than the width of a footpath. The changes come at a time when Bengaluru is already reeling under:

- Explosive urban growth that has consumed open spaces

- Outdated sewage systems with nearly 1,400 MLD of untreated waste generated daily

- Frequent floods, with stormwater drains unable to handle surges.

Shrinking buffers in this context risks pushing an already stressed system over the edge.

Read more: No scientific or ecological basis for reducing lake buffer zones: Conservationist Ram Prasad

Why it matters

Buffer zones are not ornamental setbacks; they are functional ecological infrastructure. Their roles include:

- Filtering sewage and toxins before they enter lakes

- Absorbing stormwater to reduce urban flooding

- Recharging groundwater aquifers

- Stabilising soils and preventing erosion

- Providing habitat for birds, amphibians, and biodiversity

- Regulating local climate by reducing heat and storing carbon

- Creating community spaces for recreation and education.

When buffers are reduced to token widths, all these benefits are lost. The consequences are visible in frothing, burning lakes, flooded basements, and falling groundwater tables.

A failure of governance

The KTCDA was created in 2014 to revive and protect lakes. Yet in nine years, it has:

- Failed to restore a single lake to ecological health

- Not framed rules or standard procedures as mandated

- Allowed encroachments and pollution to continue unchecked

Instead of fixing these failures, the state is choosing to weaken protections further. Governance has also been fragmented under municipal ward boundaries, ignoring that lakes and drains are hydrologically connected across the city. This piecemeal approach makes scientific management impossible.

Read more: Governance in Integrated Water Resource Management – What actions are required

The bigger picture

Legal and policy frameworks clearly support stronger protections:

- The Right to Clean Environment is part of Article 21 of the Constitution.

- The Public Trust Doctrine holds that the state must safeguard water bodies on behalf of citizens.

- The Precautionary Principle requires caution in the face of ecological uncertainty.

- The National Environment Policy (2006) recognises lakes as “entities with incomparable values” deserving exceptional care.

Diluting buffers directly violates these principles.

What can be done

Citizens can demand that the government:

- Strengthen KTCDA with accountability and transparency.

- Develop a citywide Lake & Drain Revival Plan, based on basin-level hydrology.

- Update the Drainage Master Plan to prevent flooding.

- Adopt science-based buffer norms, not arbitrary setbacks.

- Constitute an independent expert committee including ecologists, hydrologists, public health experts, and citizen representatives.

- Open draft rules to public consultation, ensuring participatory governance.

See the appendix for details of the required actions.

Why citizens must act

The consequences of buffer dilution will not remain abstract. They will be felt in flooded homes, poisoned water, depleted borewells, and rising health risks. Protecting our lakes is not just about saving birds or green cover—it is about defending Bengaluru’s right to water security and safe living conditions. As a city, we face a stark choice: protect our natural infrastructure now, or pay the price of ecological collapse later.

The question is not whether Bengaluru can afford stronger lake buffers. It is whether Bengaluru can afford to live without them.

One news item has quoted the Minister for Lakes, stating that several other cities ans states have such reduced buffer zones. This cannot be the basis for any scientific argument. Since the SC had restored the buffer zones as per the RMP 2015, then the current revision must be viewed with suspicion concerning intent. What are the compelling reasons for the current review? If the primary reason is to condone and regularise current violations (as per RMP 2015 norms) and to permit future development, then those suspicions get confirmed. As such, this revision deserves to be stopped.