Hazy mornings with the air thickened by vehicular smoke during peak-hour traffic are synonymous with Bengaluru winters. The city may have lower PM2.5 levels overall when compared to other mega cities, but high-density traffic corridors and emissions in industrial hubs are causing localised pollution spikes. A November 2024 study by Respirer Living Sciences, analysing PM2.5 pollution levels across ten Indian cities, revealed this data.

The study examined AQI information from 13 Continuous Ambient Air Quality Monitoring (CAAQM) sites in Bengaluru that recorded an average of 39 micrograms per cubic metre (µg/m3) of PM2.5 air pollutants in November 2024. This is within the 60 µg/m3 threshold but shows localised hotspots.

However, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines, 5 µg/m3 is the recommended level of PM2.5 annually and 15 µg/m3 in 24 hours. Experts believe that a hyperlocal monitoring system can address the pollution spikes and help in targeted interventions.

Identifying the hotspots

The CAAQM sites from where the localised hotspots were identified and the respective PM2.5 levels are as follows,

- Jigani: 51.7 µg/m3

- Jayanagar: 46.8 µg/m3

- RVCE, Mailasandra: 45.8 µg/m3

- Hebbal: 43.5 µg/m3

- Bapuji Nagar: 41.9 µg/m3

Particle matter in air less than 2.5 microns in diameter are PM2.5 pollutants. These are released from the combustion of gasoline, oil, diesel fuel or wood suggesting they are commonly vehicular and industrial emissions. PM2.5 contributes significantly to respiratory and cardiovascular illness with severe implications for public health.

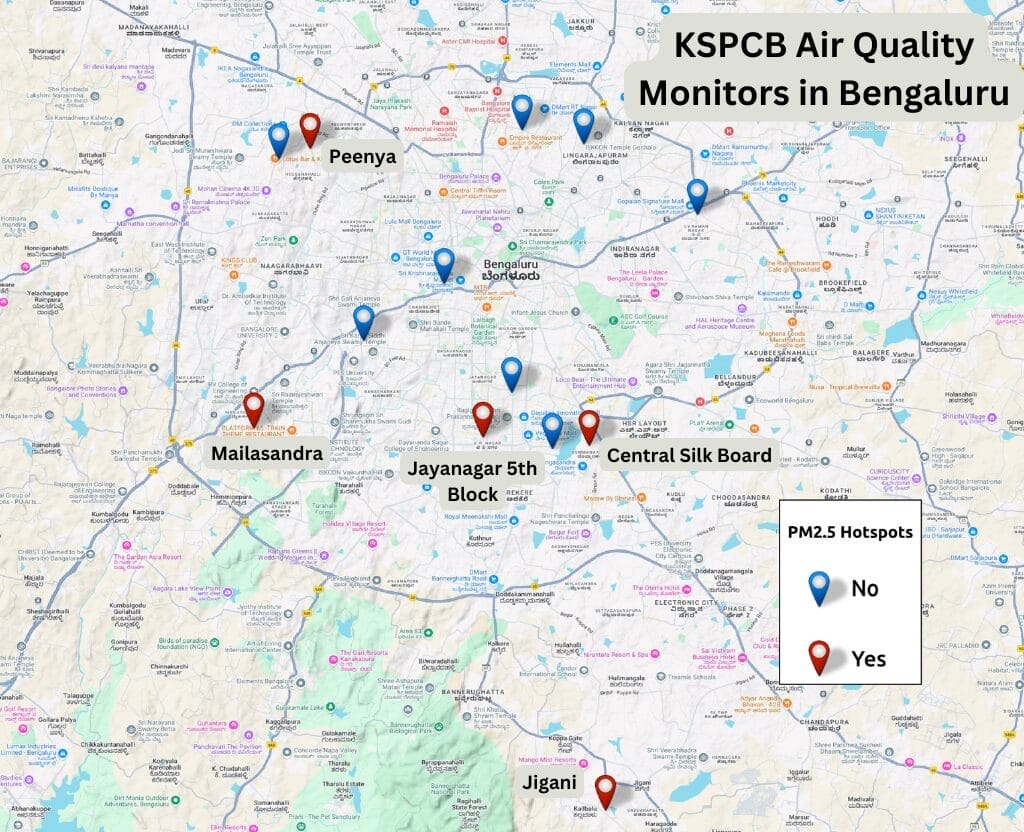

Peenya and Silk Board are identified as major PM2.5 pollution hotspots. The study used data from the Karnataka State Pollution Control Board (KSPCB) and Google AQ to measure air quality. Government sites identified Jigani, Jayanagar, and Mailasandra as hotspots, while Google AQ data revealed the highest pollution in the Jigani monitoring site, primarily representing industrial activities. Other hotspots identified through Google AQ data include Ragihalli and Badamanavarathekaval.

What are PM2.5 pollutants?

Fine particulate matter in air less than 2.5 microns in diameter are called PM2.5 pollutants. These are released through the combustion of gasoline, oil, diesel fuel or wood suggesting they are commonly vehicular and industrial emissions. PM2.5 contributes significantly to respiratory and cardiovascular illness with severe implications for public health.

Need for hyperlocal monitoring

To effectively address different pollutants in various areas, a localised air quality monitoring system is essential. The Respirer Living Sciences report suggests that hyperlocal air quality monitoring could bridge the gap between traditional broad-scale assessments and the localised realities of air pollution. Additionally, this approach offers a detailed understanding of pollution patterns and their effects, ensuring that policymakers, urban planners, and communities can take precise actions, focus on critical hotspots, and implement targeted interventions.

Meanwhile, a 2023 study by The Center for Study of Science, Technology and Policy (CSTEP) complements this approach. The study published maps that show the on-road air pollution levels in different routes in Bengaluru and the spatial distribution of ambient PM2.5. The study used mobile monitoring and city-wide 55-node stationary low-cost sensor networks for ambient PM2.5 measurements.

It found that the highest pollutant concentrations were on highways and main roads, which decreased while moving away from these areas. There were differences in pollution levels in various parts within the same neighbourhoods. Studies like this could help identify major sources of pollution and ensure targeted interventions.

“In a fast-growing and dynamic city like Bengaluru, with new constructions and increasing traffic emissions, having new measurements of pollutants and air quality is key to capturing the changing patterns of emissions,” says Dr R Subramanian, Air Quality Expert, CSTEP. While studies like CSTEP’s have limitations concerning the funding and longevity of the projects, the government must ensure hyper-local air quality monitoring.

Read more: Bengaluru’s climate challenge: How the city can reduce its carbon footprint

Mobile monitoring systems

The CSTEP study used mobile monitoring systems to study on-road emissions. The mean daytime on-road PM2.5 value, as predicted by the CSTEP study, is ~65 µg/m3, while the ambient PM2.5 values ranged between 38 and 45 µg/m3. This shows that on-road air pollution in Bengaluru is higher than ambient pollution. Major roads (including highways and the Outer Ring Road) were characterised by higher levels of pollution (PM2.5: ~81 µg/m3) compared to arterial, residential, and unclassified roads.

Clearly, on-road PM2.5 values were higher than ambient stationary measurements. The differences between stationary and mobile monitoring systems as in the size of the study area, timing, and the distance between pollution sources and monitoring networks could have added to the variations.

But the KSPCB’s stationary monitors, like the Continuous Ambient Air Quality Monitoring Sites (CAAAQMS) in 13 city locations can only measure ambient air quality and are expensive devices. Advanced technological interventions like mobile monitoring networks could help improve the air quality monitoring system.

Addressing air pollution through technological intervention

As per reports, the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) announced in 2022 that it would issue tenders for installing automatic pollution monitors across the city. But, the civic body has not provided any updates since.

Citizen Matters reached out to KSPCB to enquire about the measures being taken to improve the air quality monitoring system and analyse the sources of pollution.

A KSPCB official who did not want to be named informed that measures are being taken to check for sources of pollution and emission inventory studies have been conducted. Four CAAQM sites were installed under the National Clean Air Program. The official added that one van is used for addressing complaints, and sometimes for source monitoring.

Subramanian suggests, “Hybrid monitoring systems with the CAAQMS data as preliminary data complemented by pollution sensors and mobile monitoring systems could help capture pollution data, verify them, identify hotspots and their sources and help take required measures.” Hyperlocal air quality monitoring helps spot potential problems, figure out their causes, and identify locations with the greatest exposure risk and the most vulnerable populations.

Read more: Namma Metro construction taking a huge toll on air quality and public health

Monitoring to action

“Hyperlocal air quality monitoring alone won’t help mitigate pollution, we will need to take action based on the data. These actions need to be identified and implemented,” says Vivekanand Kotikalapudi, COO at The Infrastructure Development Corporation (Karnataka) Ltd. (iDeCK). “With hyperlocal air quality monitoring, authorities could track and identify problems like garbage burning through sudden spikes. Residents could alert the BBMP to take necessary action immediately.”

According to Vivekanand, relating monitoring with action is just about raising awareness, which will be a good start as a community. Conversations should happen on clean air — school children must be taught sustainability. Private sectors should also step up — promoting buses and metro for employees instead of individual cabs could help cut down carbon emissions. Targeted interventions like this could help mitigate air pollution in Bengaluru.

Some basic mitigation measures

Government and policy makers:

- Developing and promoting public transport, e-vehicle transitioning and better walking and cycling infrastructure.

- Regular clearing of road dust

- Tracking of vehicles with older emission control norms (BSii, BSiii) and taking necessary actions

- Planting saplings in parks and roadsides

Citizens:

- Building awareness and conversation on what is causing pollution and how it could be controlled

- Lifestyle changes — using more public transportation, cutting down on quick commerce/door deliveries that adds to carbon emission

- Transitioning to electric vehicles