The onset of Mumbai’s monsoon is loaded with a lot of speculation. Its arrival is forecasted as the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) tracks the seasons’ advance from the south. The forecast also indicates the quantity of rainfall expected across the months of June-September, leaving aside the rainfall pattern, which is harder to predict in advance.

Mumbai receives an average 2,500 mm of rainfall in the monsoon months. The city depends on this rain to fill the lakes that supply water for the year. And while this year, Maharashtra expects to surpass its average by 6%, the focus will ultimately be on if and how the rainfall pattern changes.

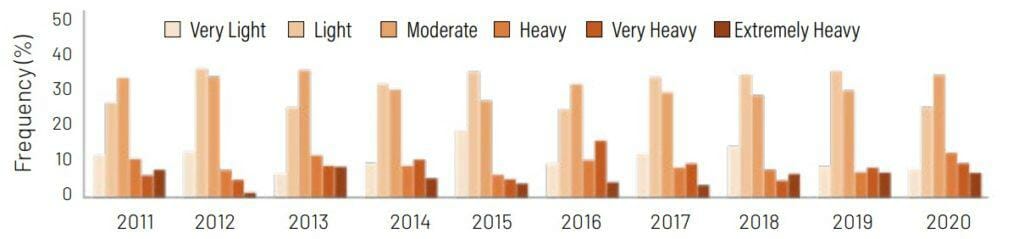

“The norm used to be light to moderate rainfall days,” says KS Hosalikar, former deputy director (general) at IMD in Mumbai and current head of climate research and services at IMD in Pune. “Now the trend is changing, and those days are reducing.” Increasingly, Mumbai’s monsoons are marked by few heavy rain days and intermediate dry periods. Experts predict that 50-60% of the total rainfall will be covered in three or four extremely heavy spells of rainfall.

The story in Mumbai so far

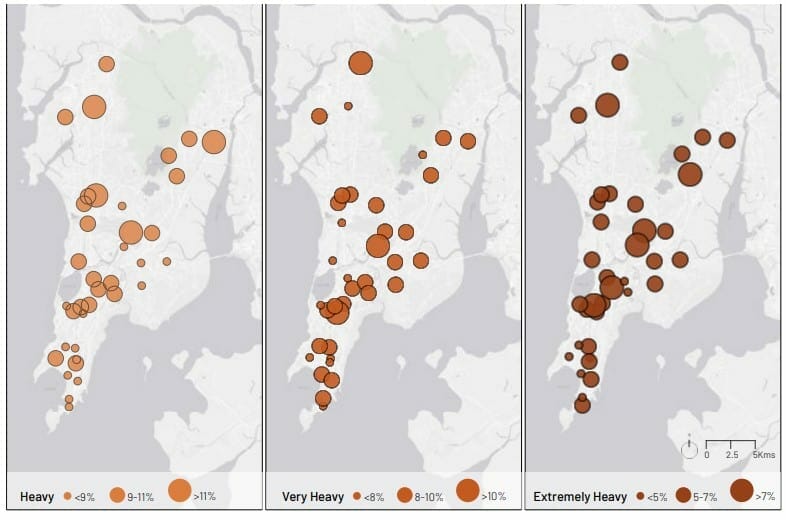

The IMD classifies the intensity of rainfall based on how much of it accumulates in 24 hours. If there is a possibility it will overwhelm a locality’s drainage capacity, it is considered an extreme rainfall event (ERE). These are divided into three categories, and come with different colour-coded warnings. Yellow alerts are given on heavy rainfall days (64.5 – 115.5 mm), very heavy days (115.6 – 204.4 mm) are orange, and extremely heavy days (> 204.5 mm) are a red alert.

In the last 10 years, Mumbai’s monsoon has seen an average of six heavy, five very heavy and four extremely heavy rainfall events in a year, according to the vulnerability assessment done by WRI India as a part of the Mumbai Climate Action Plan (MCAP). “The four-year period between 2017 and 2020 has seen a steady increase in the extremely heavy rainfall events,” says the report.

“There will be gaps in the rainfall, but suddenly, there will be a huge shower for a day, and it will make up for the last 15-20 days. So, we will get most of our rainfall in the form of very heavy and extremely heavy days,” says Hosalikar.

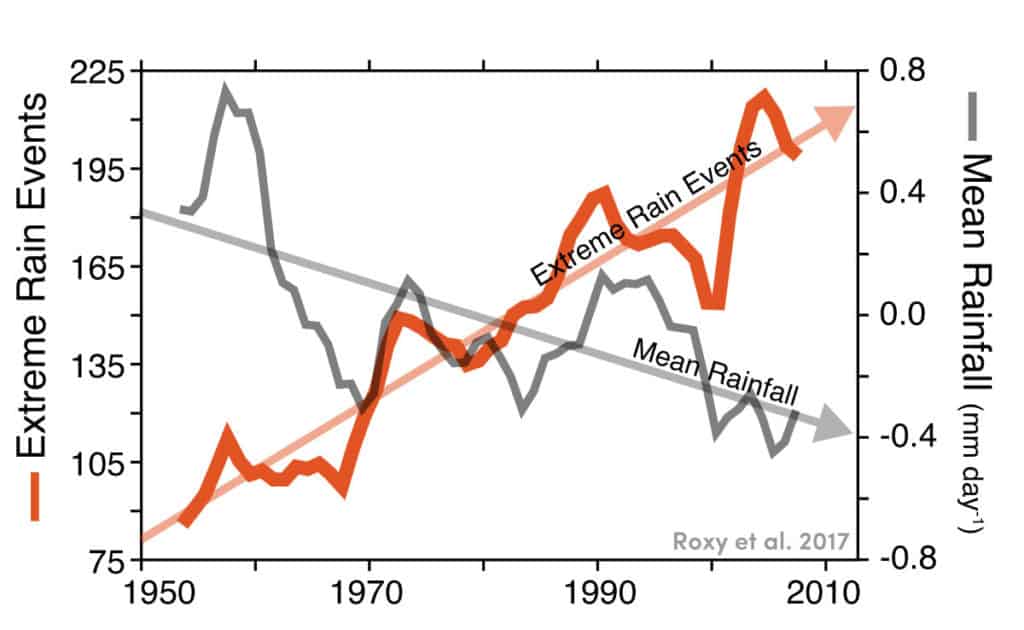

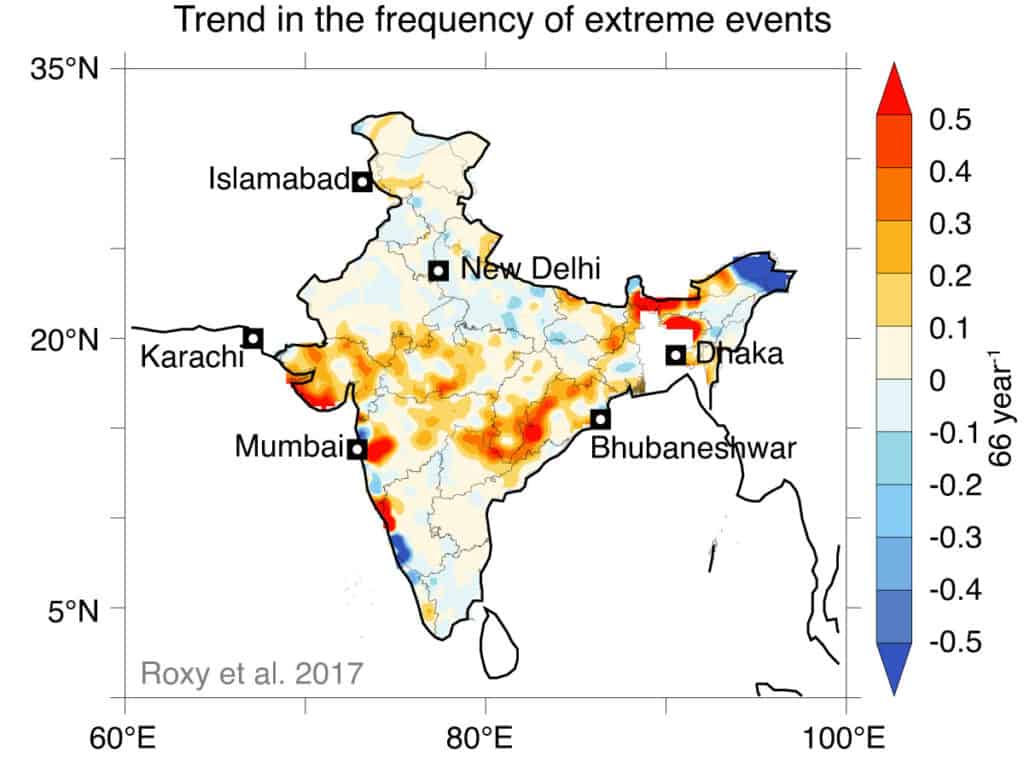

This is similar to national rainfall patterns as well. According to a study by the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM), widespread extreme rains have tripled in many states across central and north India, including Maharashtra, since the 1950s. All this while, the total amount of monsoon rainfall has decreased. “That means longer dry periods interspersed with short spells of heavy downpour,” reads an article by Roxy Koll, climate scientist and lead author of the study.

Climate change and other causes

Experts say that the erratic rainfall pattern is directly connected to climate change. “Because global temperatures are rising, the amount of moisture the air can hold increases,” says Hosalikar. “It takes a long time for the air to get saturated, and when it does, it leads to severe weather. Very tall cumulonimbus clouds form, and burst with a lot of rainfall, lightning and thunder.”

Other effects of climate change — notably a rise in cyclones and the sea level — exacerbates the ferocity and effect of the extreme rainfall events (ERE), especially coinciding with high tides. “Cyclones drive storm surges — huge waves (5 m high) that push water onto the land, flooding the coast,” writes Roxy. 2021 saw Cyclone Tauktae, bringing with it heavy rains of 230 mm in a day, a record for the month of May.

Depending upon the continued strength of carbon emissions, the number of rainy days making up Mumbai’s monsoon is also expected to go up by 3-12% in Mumbai city and 3-9% increase in the suburbs by 2050, according to a report by the Centre for Study of Science, Technology and Policy (CSTEP).

However, global warming is not the only reason to blame. Hosalikar mentions that EREs in localised pockets of the city are on the rise, which the MCAP identifies as central and western areas of Worli, Dadar, Kurla and Andheri. Building and road infrastructure, the population, green space, traffic and industries can all be contributors to the change in rainfall patterns.

Read more: Can the Mumbai Climate Action Plan (MCAP) build a climate resilient city?

The impact of erratic rainfall patterns – floods, waterlogging and other challenges

All these factors compound to increase the risk of flooding in Mumbai, along with the destruction brought by winds and landslides. The 6th Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report estimates Mumbai will face damages of up to USD 49-50 billion annually by 2050 due to the sea level rise.

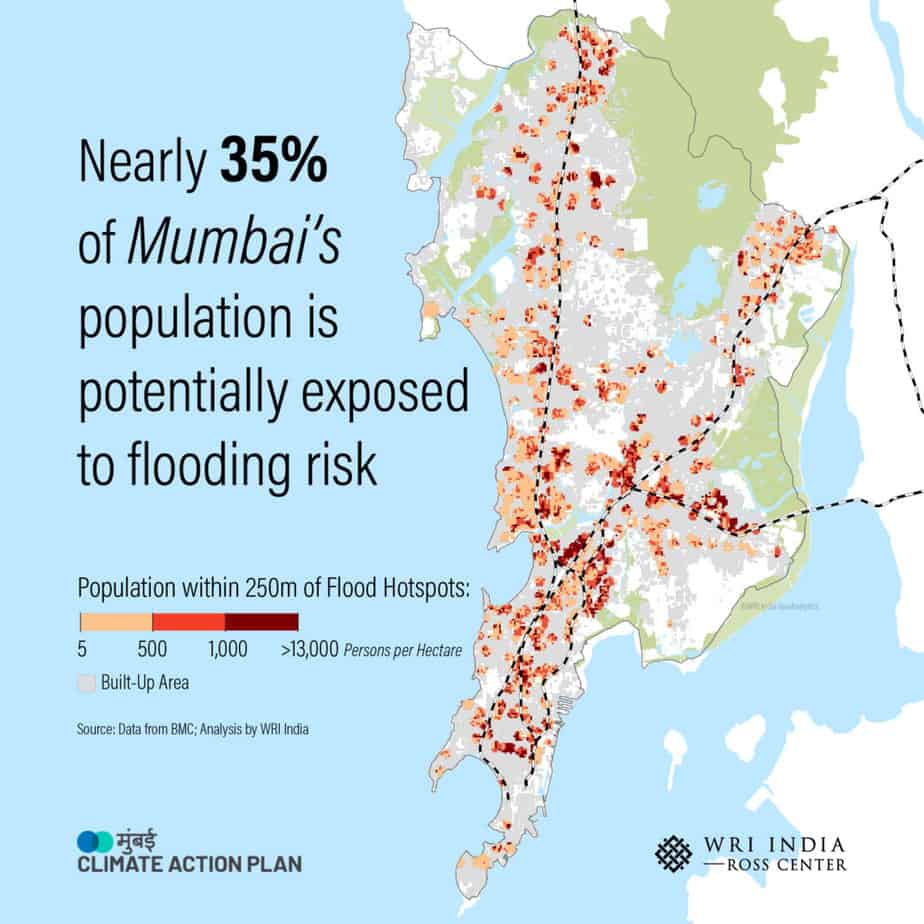

Expectedly, socially and financially disadvantaged people are the most vulnerable. Certain wards, like F/North, H/East and H/West, falling in Matunga, Bandra East and West respectively and together having a population of nearly 8 lakh, have 60% of their population are vulnerable to floods.

Most of Mumbai’s industrial and commercial establishments are also in these flood prone areas. This will hinder physical access for over 65% of the city’s formal workforce, and as is seen every year, leave thousands stranded away from their homes as the trains stop working.

31.3% of the area that make up informal settlements are within 250 m of flooding hotspots, and are at greater risk due to their temporary roofs. Unhygienic sewage disposal, lack of access to toilets and clean drinking water can also lead to serious heath hazards. “As strong winds, rains, and floods lash out, will it be those shacks that get flooded first or will it be their blue tarpaulin roofs that get blown away?” asks Roxy.

Role of disaster management agencies

“Disaster management has to play a very important role here,” says Hosalikar. Apart from the colour-coded warnings given by the IMD, impact-based warnings are also being included. These warn of areas that will be inundated with water, where there will be heavy wind, poor visibility for traffic and water over train tracks. Over 120 rain gauges in the city give updates every three hours, which is communicated via social media, SMS, email, Whatsapp, and the Mumbai Weather Live mobile app.

These measures may have reduced the loss of life due to extreme rainfall and flooding, but warnings and evacuation are not enough in the long term. “What we need to do first is a risk assessment that can demarcate the regions where the risks of floods, cyclones, and severe weather events are largest,” writes Roxy. “Based on that, we need to disaster-proof these regions, using both natural and artificial defences, and other methods.”

While flood shelters, stronger infrastructure and better access to services are important adaptive measures, the MCAP suggests increasing recreational green spaces as a mitigative measure. The loss of mangroves over the years due to various construction projects, particularly BKC, should be reversed, says Roxy. “Mangroves act as the sponge of the city, breaking the flow of flash floods and absorbing the impact.”

And while the gaps in rainfall in the midst of the season won’t spell as much disaster in Mumbai as in agricultural areas, the high humidity and heat implies oscillating between floods to unbearably sultry and hot weather.