Stormwater drains are not just “invisible infrastructure.” They are the frontline of Bengaluru’s water security. When they fail, lakes die, groundwater gets poisoned, and neighbourhoods flood. Understanding this system is the first step toward reclaiming it, because without citizen awareness, the crisis remains hidden beneath our feet.

In an earlier article, we explored how stormwater drains are the frontline of Bengaluru’s water security. Part 2 of the series shows how citizens can take action themselves by learning the typology of drains and conducting audits using simple tools.

| Accountability gaps in Bengaluru’s stormwater works Over the years, Bengaluru’s SWD network has been plagued by systemic lapses. The Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) has flagged serious issues: missing records, excess payments, and projects sanctioned without basic reference maps or master plans. Nearly half of the city’s drains have been lost to encroachments or poor planning, leaving neighbourhoods vulnerable to flooding. These findings underline a deeper accountability crisis—where infrastructure meant to protect the city’s water security has instead become a source of risk: – No records, excess payments — Bengaluru’s stormwater drain works lack accountability – 50% stormwater drains lost: Bengaluru’s flooding is no surprise – BBMP checks no village maps or master plan, while sanctioning plans |

Citizens as auditors

For many, stormwater drains conjure images of garbage-filled streams and foul stench. Yet globally, cities are reimagining drains as public spaces—like Seoul’s Cheonggyecheon (K100 – Citizens’ Water Way). Bengaluru too can reclaim its drains, but the bottleneck is accountability.

Citizen audits are a way to bridge this gap. To enable the reclaim, residents must start by auditing their neighbourhood SWDs. Here is how they can do it:

Tools for a neighbourhood audit

The audit is designed to be accessible and grounded in everyday urban experience. No technical background is required:

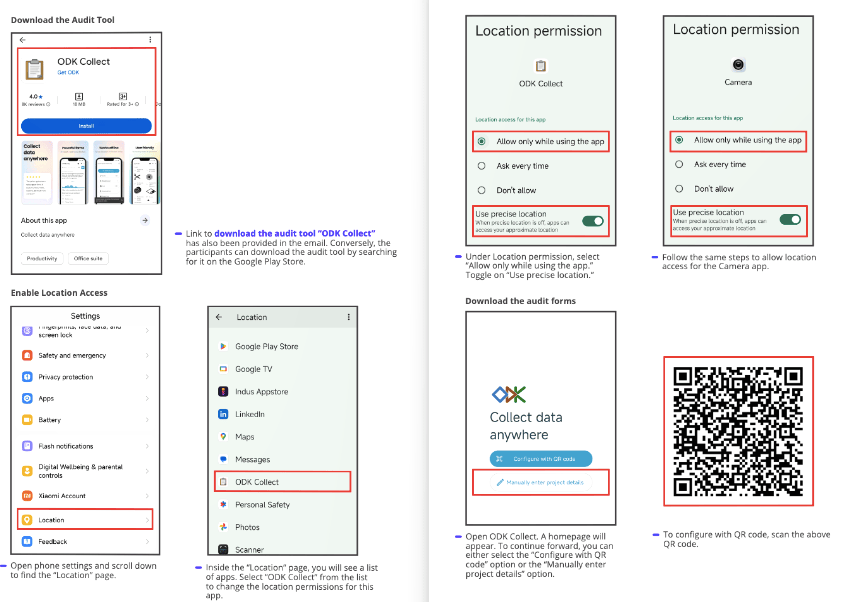

- Smartphone (Android only): The audit app works only on Android devices. (iOS users can help as navigators)

- ODK Collect App: Free app to input observations via three digital forms.

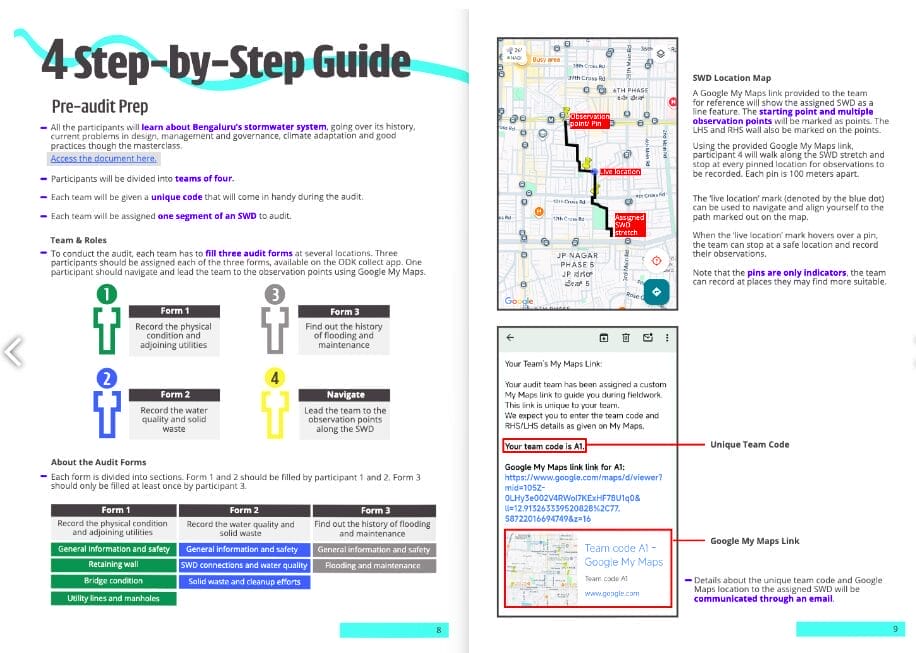

- Google My Maps: Custom navigation link with pinned points every 100m along a drain stretch.

- Phone camera: Portrait mode recommended for documenting conditions.

- Audit guidebook: Provides vocabulary and best practices for clear documentation.

Step-by-step guide

Step 1: Preparation

- Configure tools: Install ODK Collect, scan QR code for audit forms, enable GPS and geotagging.

Step 2: Form a team

Audits are best done in teams of four:

- Person 1 – Form 1: Records the physical condition (retaining walls, bridges) and adjoining utilities (power lines, manholes).

- Person 2 – Form 2: Records water quality (colour, turbidity, flow) and solid waste accumulation.

- Person 3 – Form 3: Interviews local residents to document the history of flooding and maintenance frequency.

- Person 4 – Navigator: Leads the team to each pinned location using Google My Maps.

Step 3: Fieldwork and observation

- Walk the assigned stretch, stopping at every pinned location (approximately 100 metres apart).

- Geolocate: At each point, select “Get point” in the app to record your precise coordinates before entering observations.

- Do a visual documentation: Click photos of specific features (e.g., unauthorised inlets, broken walls, or “black spots” of waste).

- Get the right images: Refer to the guidebook’s “Best Practices” to ensure photos are not zoomed too close and include the surroundings.

Step 4: Data submission

- Once the entire stretch is complete, mark the forms as “Finalised”.

- Upload and submit the results through the ODK app.

- This data feeds into a city-wide dashboard, making the “invisible infrastructure” visible to the public and decision-makers.

Towards reclaiming drains as commons

Citizen audits transform stormwater drains from neglected backwaters into public commons. By documenting conditions, citizens not only hold agencies accountable but also open the door to reimagining these spaces as part of Bengaluru’s ecological and cultural fabric.

[This is the concluding part of the excerpts from the Masterclass: Citizens & Stormwater — Participatory audits for better cities organised by Oorvani Foundation in collaboration with MOD Foundation]