It takes very little to flood a road or home in Bengaluru. In recent weeks, rains have caused severe flooding in many parts of the city, especially in North Bengaluru. A report by the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) on the city’s stormwater drain (SWD) system, released this September, shows why this shouldn’t be a surprise at all.

In any city, stormwater drains are critical for:

- Preventing flood and its related effect

- Maintaining clean lakes/water bodies

- Groundwater recharge

But Bengaluru’s drainage system has been badly mismanaged by the city corporation BBMP’s Stormwater Drain (SWD) department, finds the audit report. The report covered the years from 2013-14 to 2017-18. It was based on CAG’s audit of records at BBMP and other government agencies, physical inspections of drains, along with an independent study with the technical support of ISRO.

Where have the stormwater drains disappeared?

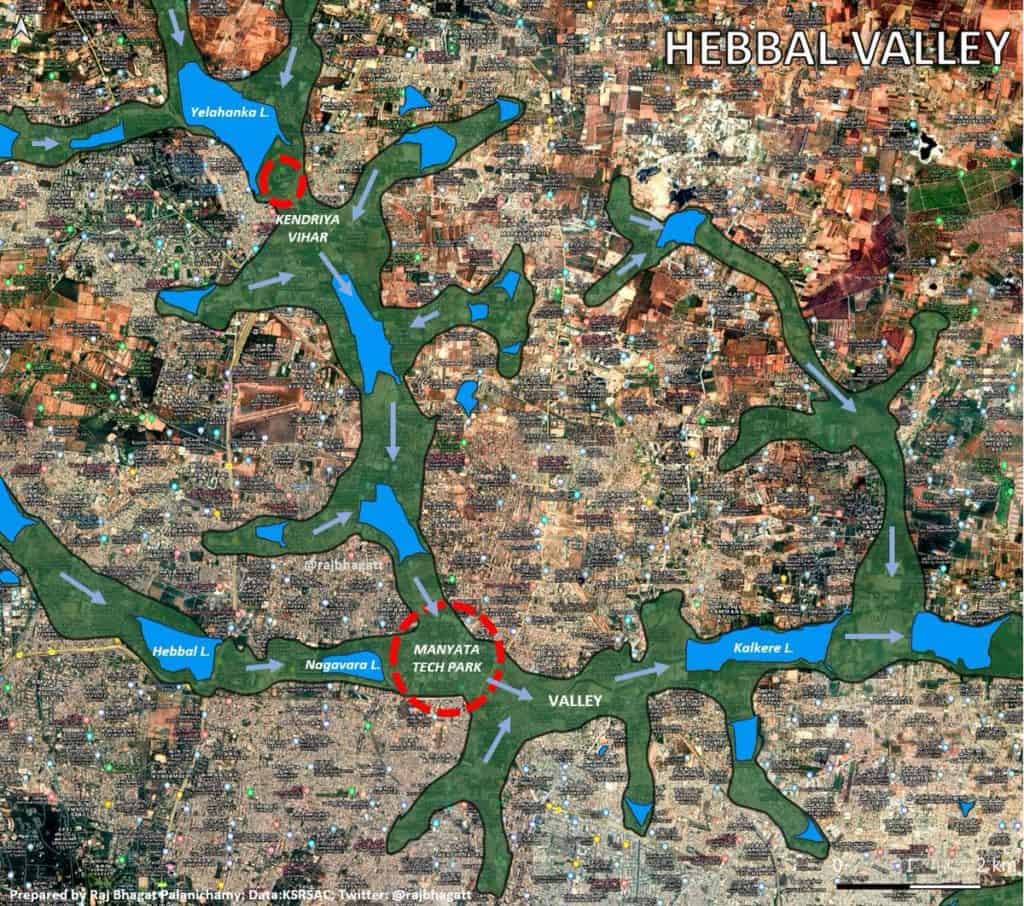

Bengaluru has a cascading drainage system wherein primary drains (rajakaluves) connect one lake in the city to another. Further, secondary and tertiary/roadside drains channelise rainwater runoff into primary drains. Uninterrupted water flow in the drains and lakes would ensure that excess rainwater doesn’t flood the city. But a large number of drains (and lakes) have simply disappeared.

The auditors’ study, supported by ISRO, showed that the total length of drains in the Koramangala and Vrushabhavati valleys – two of Bengaluru’s four valleys – have nearly halved over the past century.

Cadastral maps of the 1900s show the total length of primary and secondary drains in Koramangala and Vrishabhavathi valleys to be around 113 km and 226 km respectively. But as per the auditors’ study in 2016-17, this had reduced to around 63 km and 112 km respectively.

| Valley | Drain length in 1900s | Drain length in 2016-17 |

|---|---|---|

| Koramangala | 113.2 km | 62.8 km |

| Vrushabhavathi | 226.3 km | 111.7 km |

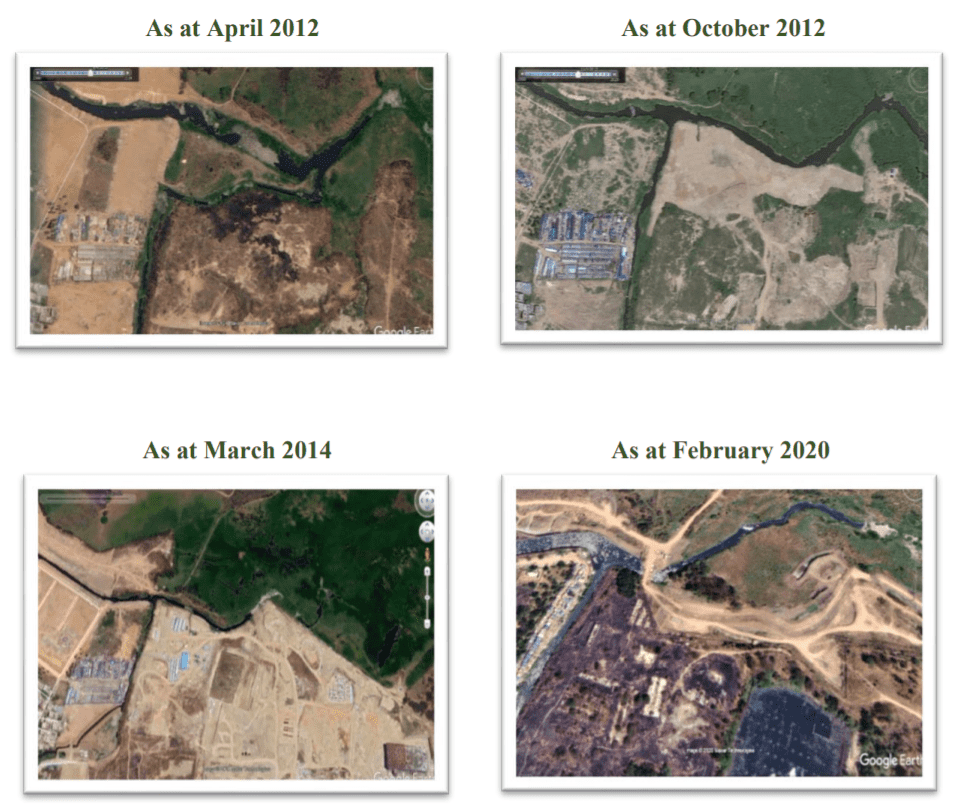

Further scrutiny showed that some drains had been covered and encroached, and in some cases the drains had been remodelled to allow illegal constructions. For example, between 2008 and 2016, the length of two drains that merge before entering Bellandur lake was reduced from 338 m to 136 m. This allowed for constructions, and affected the free flow of stormwater.

Following are Google Earth images published in the CAG report that clearly show how remodelling of the drains caused them to shrink, and facilitated unauthorised constructions around the lake.

Stormwater drains or sewage drains?

Inspections also showed that some drains were not directly connected to lakes; rather their water was channeled into diversion canals built adjacent to the lake as they were carrying sewage. This leads to overflows and flash floods. It also led to many lakes drying up and being converted for other uses. In a response to the auditors in August 2020, the state government admitted that many drains were disconnected from lakes due to the sewage problem.

Read more: Bengaluru lakes are drying up even during monsoons, here’s why

What’s more, Bengaluru has sewage lines that are often laid inside drains, even though the KMC (Karnataka Municipal Corporation) Act and the BWSSB (Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board) Act strictly prohibit this. About 780 million litres (or 54%) of the city’s untreated sewage is discharged into stormwater drains/lakes daily.

Bengaluru doesn’t have records of its stormwater drain system!

Despite the disappearing drains and the crores of rupees spent frequently on drainage works, Bengaluru still doesn’t have a complete map or database of its drainage network.

The city’s stormwater drains are mapped in two documents:

- BDA’s Revised Master Plan (RMP) 2015

- BBMP’s Master Plan of Drains

BDA’s earlier master plan for the city, the CDP (Comprehensive Development Plan) of 1995, had not marked stormwater drains at all. This did change with RMP 2015, which is the currently valid city master plan. But even as drains were mapped, they were not classified as primary/secondary/tertiary.

BBMP’s SWD master plan was prepared by STUP Consultants in 2010-11 at the cost of Rs 3.6 crore. It did classify drains as primary and secondary, but didn’t map tertiary/roadside drains at all. This is a violation of the NDM (National Disaster Management) guidelines that require a comprehensive database of all drains in cities. Tertiary drains have a critical role in water runoff since they ultimately carry the water into primary/secondary drains.

The audit report raises several questions on the way the SWD master plan was prepared as well:

- BBMP claimed that the records of tender conditions and process, payments made to the contractor STUP, etc were lost, and did not submit these to auditors. Hence auditors were not able to confirm if the master plan was prepared correctly and as per tender conditions.

- BBMP had detailed volumes of the master plan for only two zones – Yelahanka and Rajarajeshwari Nagar – out of its eight zones; the rest were missing.

- The master plan was supposed to include uniform guidelines for the preparation of DPRs (Detailed Project Reports) for drainage works in all zones. So the master plan should have been published first, followed by the DPRs for works on the drains identified in the master plan. But BBMP issued a single tender for both these, and they were prepared simultaneously. So the DPRs were prepared without guidelines, and even as the basic data of drains from the master plan was unavailable. Eventually, many works in the DPRs had to be abandoned when the contractors discovered that not enough land was available around the drains for the works. Abandonment of these works also led to BBMP losing grants of Rs 83.6 crore from the State and Centre under JNNURM, and having to use its own funds to complete the works.

Mismatch between BDA and BBMP master plans

Though the drain network in both documents are supposed to be comprehensive, some drains appear in one document but not the other. For example, a drain connecting Bellandur and Iblur lakes appears in BBMP’s master plan but not in BDA’s RMP. Some others – like an outlet drain from Sankey tank – appear in neither. That is, the city doesn’t have a reliable database or map of all its stormwater drains, which is critical for city planning, points out the audit report.

Read more: BBMP checks no village maps or master plan, while sanctioning plans

Also, neither document maps the buffer zone around drains. All drains should have a buffer zone around them, based on their classification as primary/secondary/tertiary drains. Lack of such mapping leaves drains and their buffer zones to be easily encroached by vested interests or sometimes for the laying of utility lines. During their physical inspections, auditors found that even on the ground, BBMP had not marked the buffer zones, though this is mandated as per the KMC Act.

The government now plans to construct around 90 km of concrete retaining walls for stormwater drains at a cost of Rs 962 crore to prevent areas from getting inundated. Clearly no wall can prevent floods, if we continue to build in valley areas, and don’t fix the drainage networks based on environmental principles.

[In Part 2 of this series, we look at how urban stormwater drains are supposed to be designed, and how they do get designed in Bengaluru.]

Bengaluru does not lack know how on lake and SWD system.There have been several studies and initiatives.Few years back IIM[B] started a portal to identify encroachments but had to abandon the project on the face of vested interests.What is needed is a visionary leader to launch a Mission mode project.