Buddha Nulla, or Buddha Dariya as it was once known, is a symbol of all that is wrong with Ludhiana, Punjab’s largest city. Old timers in Ludhiana remember a cool seasonal stream, a tributary of river Sutlej, that flowed through the city and rejoined the river 16 kms downstream.

“It was I think in 1977 or 78, I was in class seven,” recalls Arun Chatwal, born and brought up in Ludhiana. “Both banks of the Buddha Dariya used to be a place for social gatherings. My father used to take all of us as kids there, and some of the best memories of my childhood are of those outings”.

But Ludhiana was a much smaller and cleaner city back then with a population of 6.18 lakh. Today, memories are all that remain for residents like Chatwal, who see their city of 1,618,879 (2011 census) in an advanced stage of urban decay that some say cannot be reversed. Its roads are choked, its air is thick with pollution and lack of an effective garbage disposal system is a potential health hazard.

Just like the Dariya, which is now a nulla, or drain, a toxic, highly polluted cesspool, its banks heavily encroached by settlements housing the city’s poor.The last demolition drive to clear these mostly illegal settlements which lack basic amenities was in 2009. Since then, if anything, the encroachments have only become more numerous.

Over 1.5 lakh people living in these settlements risk serious health issues like malaria, gastro-enteritis, cholera, and typhoid besides the constant threat of being forcibly evicted. “We are poor, where else would we go,” asks Krishan Kumar, a migrant labourer working in a factory.

The foul stench emanating from the nulla, into which virtually all the untreated waste from sewers and industries is dumped, is overpowering. And it’s not that the citizens of Ludhiana are not sensitized about the grave risks of this highly polluted water body dissecting the city. There has been no shortage of expert committees and recommendations to clean up the stream.

Stream of poison

To take just one expert study, in 2008, scientists of Punjab Agriculture University led by Dr Gurdev Singh Hira and the Community Medicine department of Dayanand Medical College and Hospital conducted a detailed analysis of the level of pollution in the nulla throughout its course from Koomkalan to the place where it meets the Sutlej river. A scientist who was a part of the team said on condition of anonymity: “The water is heavily polluted, it is turbid, totally black, and emanates a stench of death.”

The study found the presence of mercury, cadmium, chromium, copper, and other carcinogens in the vegetables and crops grown in villages along the length of the nulla. Besides, it has led to heavy contamination of the ground water and tap water along its course. The water has high concentration of COD and BOD (chemical and biochemical oxygen demand), ammonia, phosphate, chloride, chromium, arsenic and chlorpyrifos. The tap water, used by people for drinking purposes had a very high concentration of lead, nickel, and cadmium. “We submitted a report, a big noise was made, but then it was put on the shelf. No one knows what ultimately came of it,” said the scientist.

Another study conducted in 2010, reached the same conclusion. Water samples contained 50 times the safe level of chromium and 20 to 60 times the safe levels of aluminium and iron besides high concentration of silver, manganese, nickel and lead. And the nullah is dumping its pollutants into the Sutlej at Wajipur Kalan, where it joins the river Sutlej downstream from Ludhiana. This contaminated water is further distributed through canals for irrigation in the entire Malwa region of the state and parts of Rajasthan. The toxic ground water has had an adverse impact on the yield of crops like wheat, cotton, paddy, potatoes, and maize among others, grown in the region.

All studies and recommendations, however, remain on paper.

Crores have been spent on ineffective and sporadic clean-up efforts. But a sustained and intensive effort, as recommended by all the expert committees, is nowhere on the radar of the city administration or the state government. What is worse, since 2002, successive state governments in their wisdom, have constructed multiple dams over a 15-year-period near Koomkalan, where the stream from the river enters the city, which first reduced and then totally cut off fresh water from Sutlej flowing into the nulla.

High risk zones

The pollution has had a deadly effect on people of the Malwa region. With carcinogens ultimately ending up in the food chain, this region has the highest concentration of cancer patients in India.

As per a 2015 government study, the districts of Muktsar, Mansa, Bathinda and Ferozepur have an average of 107 cancer patients per 100,000 population. Among these, Muktsar is the worst with 136 patients per 100,000 population. The high chemical toxicity in the groundwater, particularly arsenic and uranium, has ruined many lives in the region.

“The impact of pollution in Buddha Nullah has been felt across the Malwa region,” said Dr Aswhani Kumar of Dayanand Medical College and hospital in Ludhiana. “Neither is the medical infrastructure here adequate. Due to the high propensity for cancer, people should get themselves screened regularly for visible signs like a lump in the throat. Health authorities need to spread more awareness.”

The approximate two million residents (as per latest population estimates) of Ludhiana are solely dependent on ground water, drawn mostly through hand pumps and electrical motors, for their day to day water needs. Citizens have installed high strength water filtration units in their homes. “The entire population is at a high risk of contracting serious diseases,” said Dr Arun Chatwal, a private medical practioner. “We have seasons for different diseases. For example, now that the summer is here, we are getting ready for a spurt in gastro-intestinal diseases”.

Attempts to clean Buddha Nullah

Successive state Governments have been making noises from time to time to rectify the situation. In 2009, the Government imposed section 144 around the nullah, banning the disposal of garbage into it. But it was quickly forgotten, and the volume of garbage dumping increased even further.

According to an ‘action taken report’ released by the government in 2018, the state and Central governments have spent Rs 550 crores in their cleaning up operations, but the level of pollution continues to climb further. Unfortunately, there have been few proactive steps taken by citizen groups to force the administration into action. “People are more concerned about their own personal agenda rather than the common cause,” said Karanbir Singh, a resident.

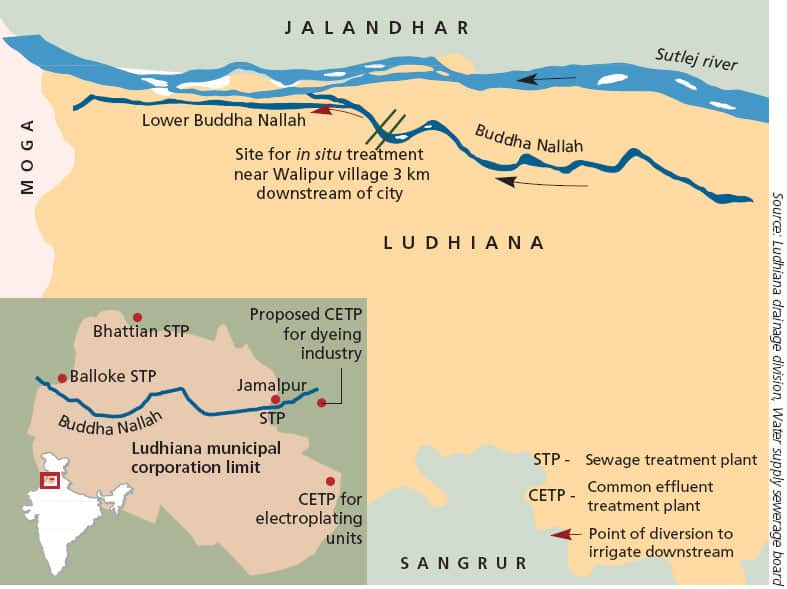

In 2011, Jairam Ramesh, Union Environment and Forests Minister in the then Manmohan Singh led Congress government in Delhi, initiated a bio-remediation project for Buddha Nullah. Bacteria was released near Wallipur village to clean the stream. But the exercise was a complete failure: the level of pollution was so high that the bacteria failed to grow!

Again, during the previous state Akali regime, former Chief Minister Parkash Singh Badal paid Rs 3.4 crore from the state’s coffers to Engineers India Limited to prepare a detailed project report for cleaning the nulla. The report was submitted but once again, nothing was done on the ground.

Political parties have been blaming each other for the present state of affairs, but residents say there is no political will to clean up the drain. For instance, Ludhiana has only three Sewerage Treatment Plants (STPs) with a total capacity of 311 MLD, against a capacity requirement of 750 MLD. Even these three plants are often non-operational due to technical reasons, which means that the entire raw, untreated sewerage of the city is dumped into the nulla.

After assuming office in 2017, local bodies minister Navjot Singh Sidhu decided to approach Baba Seechewal, an acclaimed environmentalist who is credited with single-handedly cleaning up Kali Bein, a similar highly polluted stream that flowed through Sultanpur Lodhi of Doaba. Sources, however, say that Seechewal may not have an answer to the problems of Buddha Nulla, given the stark difference between the two places (Sultanpur Lodhi is not an industrial town). This writer’s repeated efforts to get Sidhu’s views on this received no response.

Meanwhile, citizens point out that while the administration is running around in circles, the solution to cleaning up the nullah is simple:

- Ban or shift industries such as dyeing units and electroplating units that have been dumping toxic material into the nulla.

- Ensure that the treatment plants set up by industrial units are operational. Residents living around these units say a majority of the plants were set up only as a show of compliance with the rules, and are largely non-operational. Industries continue to dump their waste directly into the nullah.

- Operationalise Sewerage Treatment Plants (these fall under the purview of the Municipal Corporation) and stop dumping untreated sewage into the nulla

- Bar the large number of dairies in the city, some of which are owned by local politicians, from dumping their waste in the nullah.

- Instead of cleaning the nullah on a piecemeal basis every year, the Municipal Corporation (MC) ought to focus on sustained efforts to implement the various expert recommendations.

Annual reports of the Corporation reveal spends amounting to more than Rs 1 crore every year to clean up the nullah, removing debris, plants and other waste, but its condition goes back to what it was within a month or two.

Now a new promise

Talking to Citizen Matters, Punjab Pradesh Pollution Control Board (PPCB) Chairman Satwinder Marwah says that the matter has now been taken up by the National Green Tribunal. Heading a three-member NGT panel, Justice (retd) Pritampal Singh expressed extreme displeasure over the state of affairs and has directly laid the onus on PPCB and the Ludhiana Municipal Corporation for the nulla’s deteriorating condition. “It seems that nothing has been done so far to tackle this problem,” he said during his visit on May 1, 2019.

PPCB’s Marwah says the NGT committee formed to oversee the nulla clean-up has now fixed clear responsibilities on the role of the stakeholders. “Now, the stakeholder departments, mainly the PPCB and Ludhiana MC, cannot indulge in blame games. An Executive Committee will take follow up action on the NGT panel’s recommendations and those found lacking will be penalised,” he said. “You will see visible changes within the next two months”.

The NGT panel has asked the MC to make Buddha Nullah garbage free, increase staff at sewage treatment plants, install CCTVs in the treatment plants along the nullah and to seal the points used by the MC for dumping raw sewage. “The problem is high level of corruption both in the MC and the PPCB,” admitted a municipal corporation official. “People tend to cut corners for personal gain. This time, the NGT is fixing individual responsibility of different divisions of the MC. Officials will have to act on it.”

Meanwhile, the newly elected Ludhiana MP Ravneet Singh Bittu, who is representing Ludhiana in the Lok Sabha for the third time too has declared cleaning up the nulla as his first priority. “We will restore it to its earlier avatar of Buddha Dariya,” he has promised.

Hope certainly springs eternal.