Travelling within Bengaluru City has become a chronic nightmare for all its citizens. Even as people grapple with never-ending traffic jams, the government has come up with various ideas to solve the issue, including the much debated elevated flyover and the pod taxi project.

But are decision makers losing sight of the broader context and framework within which the traffic situation must be viewed? Is there a deep enough understanding of the nuances that need to be considered for the gridlock to be broken and the efficiency of solutions multiplied?

Professor Ashish Verma

Talking to Citizen Matters, Professor Ashish Verma deconstructs the overall public transport scenario and discusses what could work for a city like Bengaluru.

Urban transport planning follows basic principles of mode systems to ferry people from point A to point B. Can you explain these concepts in a nutshell?

Public urban transport systems are largely of two kinds – Main mode and Access mode. Main Mode, as the term suggests, is a high capacity mode transporting larger number of people within a city. It sometimes has dedicated infrastructure for its movement, that is largely rigid in nature.

Access Egress or Access mode describes a lower capacity system that should provide last mile connectivity and therefore be more flexible in its routes and movement.

These systems are then designed based on demand, cost and sustainability. There are other parameters too, but these are the three main components.

How do these parameters work? What are the considerations for each of them? Is it just financial cost and speed?

To ascertain demand patterns, we look at concentrations of travel, passenger volume, hotspots, the current preferred mode of transport i.e. how people commute between different areas. Sustainability is also looked at from three angles – social, environmental and economical. The cost of the project needs to be justified on these parameters, and varies depending on the infrastructure requirements.

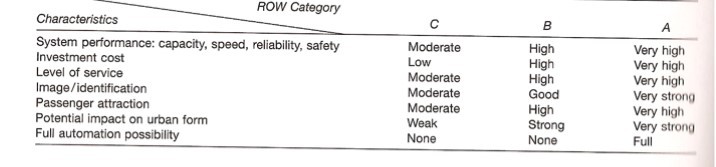

The infrastructure requirements would depend on how the system works. These systems operate three types of Right of Way or ROW- They are ROW A, B and C.

ROW A is where they have a dedicated infrastructure for themselves, like the metro system, suburban trains or now the pod taxi that is being suggested. It is totally exclusive and doesn’t intersect with at-grade traffic, which in simple terms, means on-road traffic. The benefits of ROW A systems are speed, riding quality and safety. They are rigid systems requiring extensive infrastructure which will not be flexible and have high costs.

ROW B is where these public transport systems have at-grade dedicated lanes, but overlap at junctions or traffic signals etc., such as the BRTS system or trams. They thus enjoy partial exclusivity.

ROW C is where the public transport moves in mixed traffic, as is the case with the BMTC at present.

In Bangalore, as designed public transport systems, the BMRCL and BMTC are the main modes. BMTC also acts as access mode transport for the BMRCL.

Given the growth spurt that Bengaluru has seen in the last two decades, how do you think the government ought to be planning for a city that would soon grow to be one of the most densely populated globally?

Our planning should be precisely to ensure that doesn’t happen! We cannot allow Bangalore to grow like this and hit a 3-crore population. We need to control it with policies. Create suburbs. The decentralisation of Bangalore as an economic hub of paramount importance has been largely hindered by the fact there isn’t proper connectivity. I have been arguing for high speed rail connectivity in the state that will thin this concentration.

Urbanisation and economic opportunities are very skewed in our state and it is centred around Bengaluru. The city is well-connected internationally and nationally. But where is the connectivity of Bengaluru to other parts of the region?

Think of a situation where Bangalore and Mysore travel time is just 30 minutes via high speed train. What are the possible consequences? People will live in Mysore and may travel to work to Bangalore. Frankly it will be easier to do that than try and navigate between Sarjapur and Manyata Tech Park.

Some establishments may shift to Mysore which also reduces the capital requirements for setting up shop. You have got to build an integrated system taking care of regional connectivity as well within the city. The important advantage of High Speed Rail is its connectivity and location of their stations within the city and their integration with access egress.

Last mile connectivity in the context of Bengaluru has been abysmal. How does one improve this?

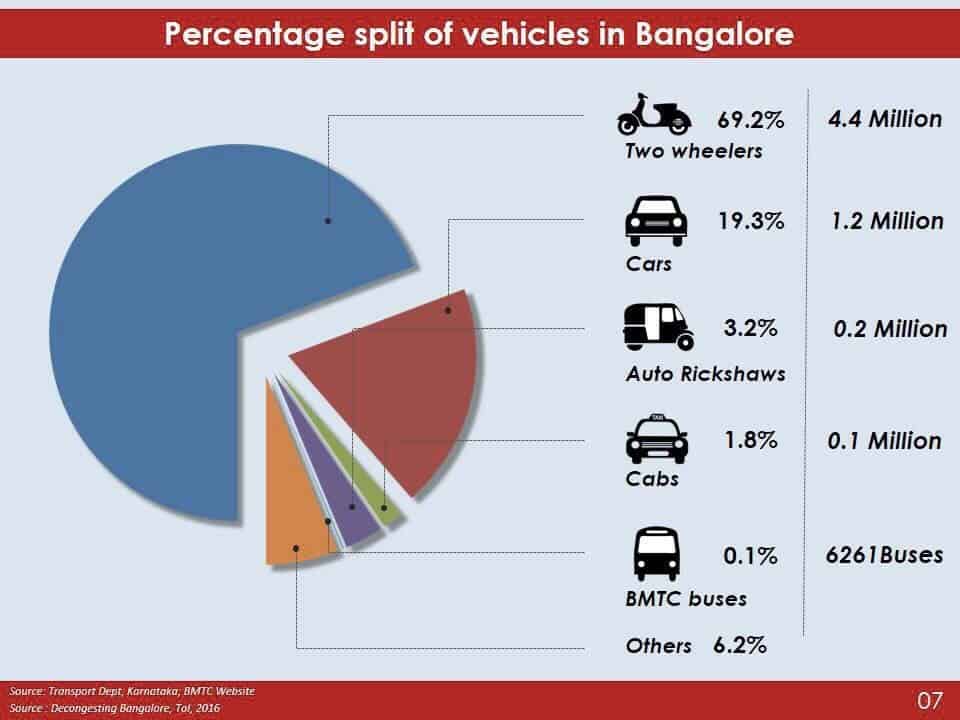

Be imaginative. For example, consider the auto rickshaws that are not being regulated for their role in mobility. If you get a system in place, you can run them as feeder systems on shared basis, making it economical as well. E-rickshaws are a wonderful option. It will provide you door-to-door service. You need to create an attractive, integrated door-to-door system, then people start shifting to it. The balance comes about automatically. We complain about the number of cars on the road. But you if you provide quality ridership options that are more attractive, there will be an automatic shift.

Provided by Professor Ashish Verma

What about walking?

Well, I would love it to be last mile connectivity, The causal effect of increased walking is very important in the overall health of the city, which sadly is not even a consideration during planning of urban mobility. But the fact of the matter is that pedestrians today are an endangered lot. Pedestrians are running for their lives. Where are their priority lanes? The footpath infrastructure is terrible. You suddenly come upon dead ends and have to step on the road.

The last comprehensive report on Household Travel Survey was done by consultants Wilbur Smith in 2008/2009. The report was never released by the Government. We used raw data from the report for our research, and found that walking was a preferred mode of access for a distance of about 500 metres. In some specific cases people preferred to walk up to 700 metres. We call this acceptable distance, which drops in the context of Bangalore after these numbers.

However in Germany or Zurich, the acceptable distances go up dramatically. People prefer to walk longer distances in these places. In Paris, the modal share of walking is 60% and the metro is available to reach anywhere in the city. Zurich is even better. The tram there is a glaring example of public transport providing almost end-to-end connectivity. We need to be demanding these facilities instead of encouraging flights of fancy, such as pod taxis.

There are many examples of systems being put in place within already existing systems. The fact they have announced an integrated system authority is a right step but ultimately it will depend on the model. But it will still be chaired by the Chief Minister which should not happen. Because then it becomes politically driven.

We just need to think globally, but innovate locally. Transport at the end of the day is part of the urban ecosystem. The urban ecosystem is a socially vibrant space that needs to thrive. Decongest the central business districts. Make it pedestrian and public transport only.

It is a flawed argument that businesses will be hit if you ban private vehicles. In fact, studies around the world show that when you decongest areas, businesses thrive.We need to have romance for our city and a city is more than just its transport systems. You cannot destroy the whole ecosystem to save a few minutes.