Books connect readers to voices from the past, from alternative universes, from lives of people we don’t know. Books transport us to unknown worlds, while simultaneously revealing and helping us interpret the realities of our own. Books transform, by making us think, wonder and find our own voices. Public libraries, therefore, can be the centre of such transformation — for both individuals and communities.

Libraries, however, can be more than a repository of books. During the pandemic and subsequent lock down, community-run free libraries in India educated its members on social distancing and masking, helped them book vaccination appointments, filled the days of homebound children and even connected members to organizations providing rations and relief material. Thus libraries can turn into a space for community to gather, or double up as vocational training centres or cultural centres. They can act as voting stations, polling stations, a space from residents to access the Government and vice versa.

Read more: Books in their hand, dreams in their head: Community library project changes kids

The UNESCO Library Manifesto 2022 posits the public library (i.e. state run libraries which can be accessed by all) as the local gateway to knowledge that provides a condition for lifelong learning, independent decision-making and cultural development for individuals and social groups.

How many public libraries does India have?

Freedom, equality and access to knowledge are fundamental human values and our constitutional rights. Unfortunately, in our country, we find that economic and social inequalities are all too real and common. These values and rights can move from abstract to real only when well-informed citizens can effectively exercise democratic rights. A robust, active public library infrastructure can go a long way in creating such a mass of active citizens.

How many libraries do we need to create this mass of informed citizens?

Most library scholars point to a recommendation of the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) — one public library for every 3000 people. So how many such libraries do we have in India?

Since 1947 there have been no official figures on the number of public libraries in India. The Ministry of Culture, while overseeing six national libraries, does not have a department devoted to public libraries. At present, this work is being carried out by the Raja Rammohun Roy Library Foundation (RRRLF), established in 1972.

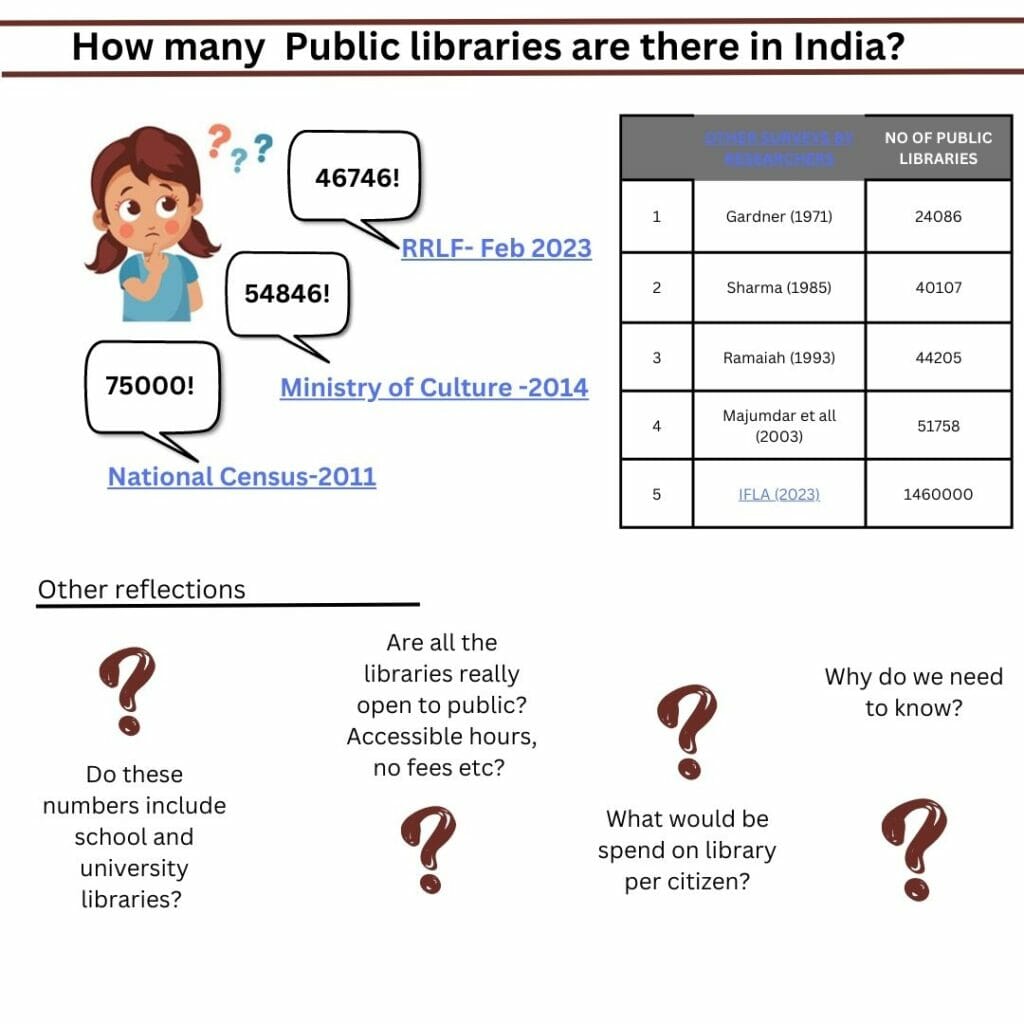

According to Raja Rammohun Roy Library Foundation (RRRLF) we have 46,746 public libraries as on date. A 2014 report by the Ministry of Culture (MoC) relies on a survey that says we have 54,846 public libraries. The 2011 National Census states 75,000 libraries. Yet other figures emerge from other surveys by independent researchers, including a figure of 1,46,000 libraries from the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA). [See infographic below]

According to Preedip Balaji, Librarian at Indian Institute of Human Settlements, who keenly believes in the power of libraries to transform communities, there is simply no aggregation of data at a national level on the number of libraries we have. The data at the state level is also hard to find in many states.

Preedip has sent RTIs to the Ministry of Culture and RRRLF etc to gather the exact number of public libraries in India, and has also tried to arrive at a figure by poring over census numbers and research by other scholars. Without this information, how do we even know where we have to go, he asks.

Who is in charge?

National Level

Historically there have been attempts to create a national legislation or national policy to oversee development of public library infrastructure in India. S.R Ranganathan, considered the father of library sciences in India, created model legislations for free, accessible libraries. These were never passed.

A National Policy developed in 1986, with a similar premise of free and accessible public libraries as a right, met a similar fate. Libraries are not well integrated as instruments for learning and development in the National Policy on Education. At present we have the National Mission on Libraries launched in 2014, by the Ministry of Culture and with RRRLF as a nodal agency. This mission has been a disappointment so far. In any event, missions, by their very nature, are time bound and limited.

State Level

Nineteen out of 28 States and 6 Union Territories have passed Library Legislations. Most states do not report statistics on public libraries in the State though they are meant to. In Tamil Nadu, districts publish statistics pertaining to public libraries in their annual District Statistical Handbook. Other states report differently. Some don’t.

The administrative structure varies from state to state. Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka, have a Department of Public Libraries and Director of Public Libraries. Tripura State Central Library and Haryana’s public libraries are managed by the Department of Higher Education. In other states it falls under the department for culture.

In many states, no qualified professional library staff are appointed, rather officers of the culture/education/art department look after library affairs, while usually handling additional responsibilities. This makes it difficult for citizens to even understand who or which agency to petition, to improve access to public libraries.

In almost all states, the local departments of libraries point to lack of funding as the main impediment to offering services. Some state libraries are funded by fixed grants that have not been revised from the time of their legislation.

Six states charge a library cess to finance and run state libraries. This is a much more dependable funding model. Citizens are charged a tax which is meant exclusively for library development. However, here too there are cases where local municipal bodies, which collect this tax, do not make timely payments to the public library departments.

For instance, in Karnataka the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP), owes more than Rs 226 crore to the Department of Public Libraries as on 2019. Show cause notices and threats of legal action have made little difference. As citizens we need to be aware of why our taxes are redirected. There is enormous public pressure for municipalities to spend on roads and other infrastructure, resulting in areas like libraries getting overlooked.

Read more: Why there is a need to revamp the Karnataka Public Libraries Act, 1965

Public libraries: Reach and inclusiveness

Since there is no national policy, many state legislations do not define public libraries. The result is that even where we have state legislations setting up libraries, they may not be truly accessible to all. Many public libraries charge fees and/or security deposits.

The Delhi Public Library charges Rs 25-100 as an annual membership fee. The State Central Library in Jayanagar, Bangalore charges 200 as lifetime membership fees. The State Central Library in Cubbon park is a reference only library with no fees but no facility to borrow books. In Chennai, there is an annual fee of RS 10 and a deposit of up to Rs 50 to borrow books.

True, these fees are nominal. However, in our country where a large percentage of the population spends Rs 6 out of the 10 that they earn on food, even “nominal” fees become barriers. Second, when there are taxes funding the libraries and they are ‘public’ libraries, why charge a fee at all?

Free libraries reflect that the space is open and welcoming to all. Added to this is the bureaucracy involved in filling out forms and registering as library members. Most public libraries have no specific programmes to extend library services to those that feel its need most – those who are first generation readers, or those who are left out of formal educational institutions.

School shutdowns during the lockdown showed us two Indias – one where some children thrived in online classes, one where the latest ASER (Annual Status of Education Report) 2022 shows nearly 58% of class 5 children are unable to read class 2 text. Public Libraries can help bridge these gaps with specific outreach programmes to address the barriers to reading its community members may have.

A recent survey released by the National Mission on libraries shows that there are hardly any children or differently-abled persons among library members. The number of women members is also low. We want a public library system that serves all – to show us what inclusive spaces should look like, to reflect that all citizens have a right to access information, to make sure communities can come together in a productive way to exercise their rights.

Gramotthan, a free community library in Odisha under the Free Libraries Network. Pic courtesy: Madhumita Rajan

Rays of hope

Public Libraries can also have a significant role in strengthening democracy, levelling social inequities, and providing a connection between citizens and their government.

Kerala, with the largest number of public libraries is also the state with the highest level of literacy. The Kerala model shows us, in fact, that decentralisation and providing autonomy to local bodies can help create a dynamic and thriving public library culture.

In Kerala libraries are registered as a trust or society and owned by the people and then affiliated to the Kerala State Library Council that ranks libraries into grades and provides some amount of financial assistance. The grading system incentivises the libraries to adhere to certain standards, but the libraries themselves are free to run themselves independently, have independence in staffing, book curation and even the ability to raise additional funds. There are close to 9000 libraries in the state of Kerala alone and most of them see regular visitors and members.

The challenges in setting up a robust public library infrastructure are big but not insurmountable. There are many free libraries all over India. The Free Libraries Network is one such collective, with over 150 constituent libraries, that demonstrate how libraries have transformed their communities. It also shows us that our communities are coming together to address the inequalities in access to books and information.

Non-negotiable requirements for an effective library policy

- Recognizing free library services for the people as a matter of rights and access

- Creating a system to drive implementation of state legislation

- Committing statutory source of funding

- Data and infrastructure

This is a wonderful article. Not a day too early!

Can we aim for at least one public library in each Ward? This seems reasonable to me. The state government can prepare a plan to get this done in a phased manner.

Of course, having space and funds for enough books and library services is a prerequisite.

A large number of book donors seem to exist in Bangalore (and possibly in most cities). They can be a large source of supply.

EXCELLENT INITIATIVE.