India’s richest municipal corporation has found itself in a logjam. The pandemic has impaired its ability to meet expenses, even though its budget remains unspent year after year.

In this series of articles, we will explore the Mumbai civic body’s financial might, the governance and procedural challenges in raising or spending money, and ways to finance expenditure due to the pandemic and the slowing economy.

For the past few weeks, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation has been reporting a severe cash crunch. It has slashed its capital expenditure by Rs 2,500 crore, imposed a 20% cut on its revenue expenditure, and also denied full salaries to a part of its staff. In August, it sought Rs 200 crore from the State Disaster Relief Fund (SDRF) to fund expenditure related to COVID-19.

This downturn of the country’s richest civic body, with a budget bigger than states like Goa or Mizoram, is surprising.

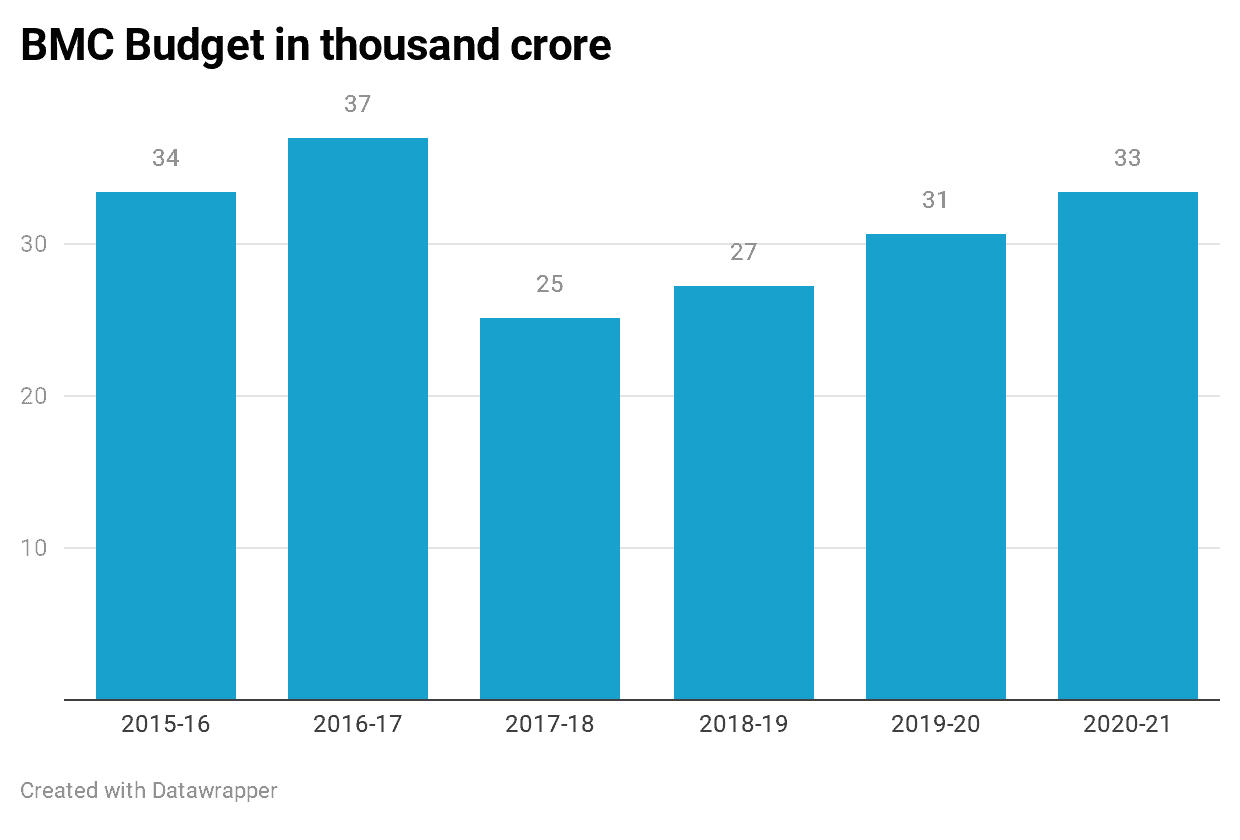

Over the past several years, the Municipal Corporation’s massive budget has repeatedly made news.

What has also made news is the municipal corporation’s inability to utilise a large chunk of it. From 2007-2017, according to the Hindustan Times, BMC’s total budget amounted to Rs 2.19 lakh crore, of which it spent close to Rs 1.74 lakh crore.

Over the years, this unutilised fund has accumulated as a huge corpus. It’s locked up in fixed deposits with BMC’s current cash reserve at Rs 78,669 crore.

BMC is now tapping into this emergency fund to finance COVID-19 related expenditure. But experts suggest that this could be an appropriate time to focus on long-term financial management.

BMC’s balancesheet

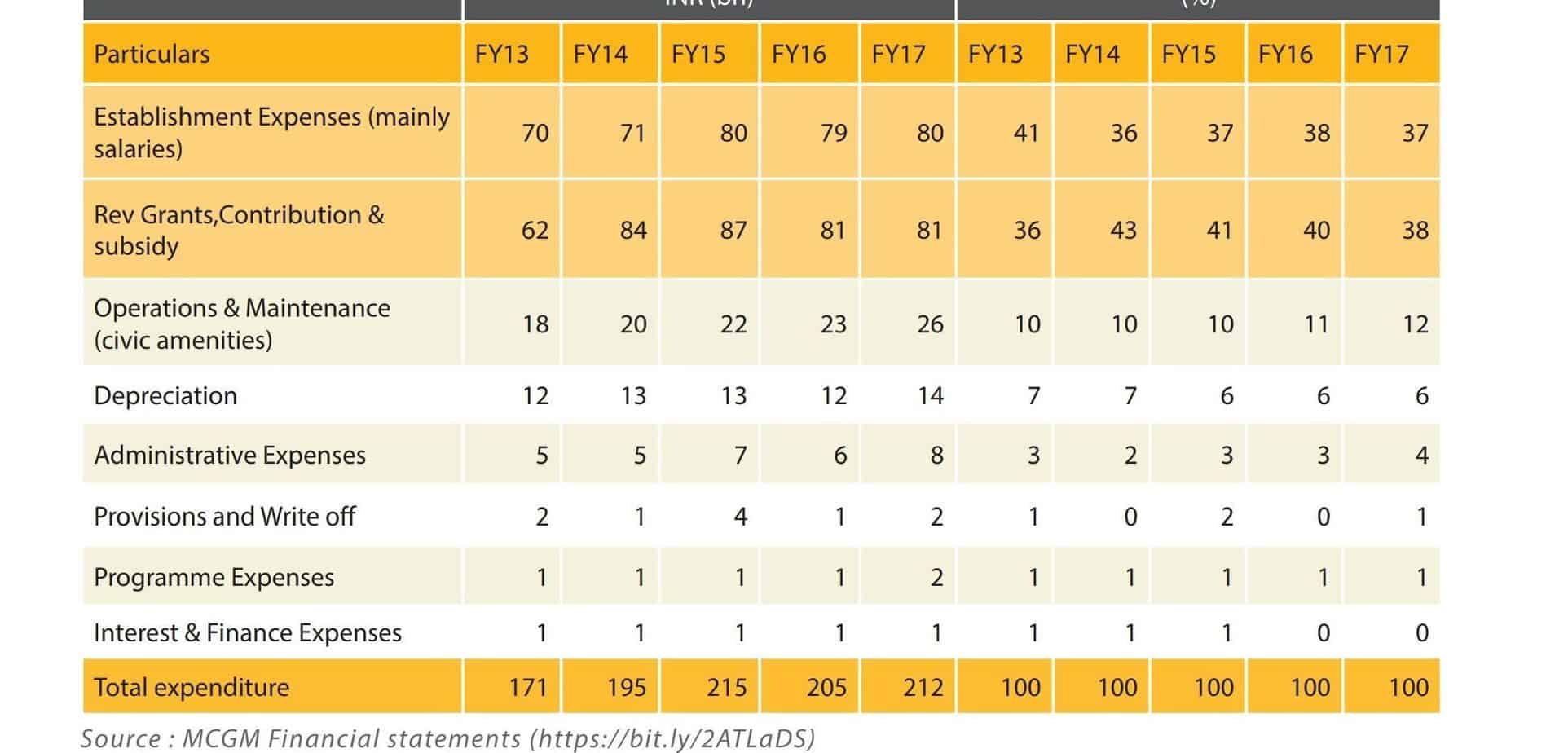

Janaagraha, a non-profit trust focused on civic reform, analysed BMC’s financial statements from 2013-2017. They found that a lion’s share of the civic body’s expenditure is spent on “administrative expenses” such as salaries. From 2013-2017, the proportion has hovered between 36% to 41%. The proportion of expenditure on “operation and maintenance (civic amenities)”, a core responsibility of the civic body, has barely been 10% from 2013-15, increasing marginally to 12% in 2017.

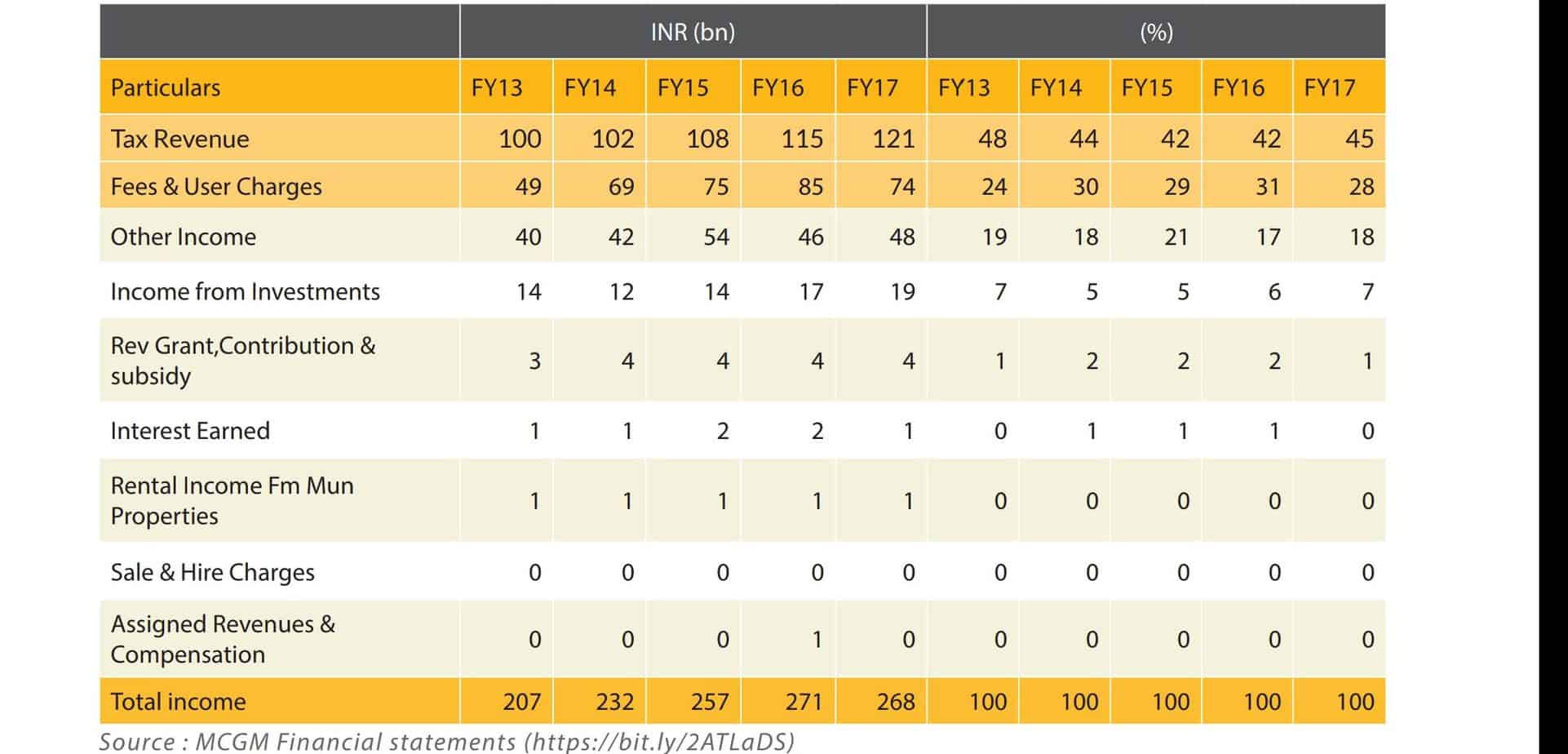

The civic body’s largest source of income is tax revenue such as street, sewerage or property tax, which has grown from Rs 100 Billion in 2013 to Rs 121 Billion in 2017, according to Janaagraha. Its other source of income is fees and user charges, income from investments, and revenue grants.

MCGM receives nearly 71-74% of total revenue in the form of tax collections and fees & user charge, according to Janaagraha’s financial analysis of the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation.

During the past quarter, the corporation’s income through taxes has plummeted. Collection of property tax and water and sewerage tax has been pending, causing a cash crunch. But the slowdown is not induced by COVID-19-related factors alone.

Budget in deficit

Early this year, BMC’s budget was in deficit due to a slowdown in the economy. While this is routine for most other states and municipal corporations, it is unusual for the civic body. The falling demand among real estate developers as well as a loss of funds because of the removal of Octroi, a local tax imposed on goods entering a city, and its replacement with the Goods and Services Tax, were attributed as key reasons.

BMC’s fiscal clout, Professor Anita Rath at the Tata Institute for Social Sciences, says, was because it retained “a lucrative but obsolete source of revenue, octroi. It provided the city with day to day liquidity and built-in buoyancy in the revenue system.” In 2016, Octroi accounted for 23% of total income, according to Janaagraha.

Now with its replacement with GST, the onus is on the state governments to compensate urban local bodies. But due to the economic slowdown, the centre is not compensating states adequately for GST, and the state is not contributing to urban local bodies (such as municipal corporations) for Octroi.

“(Cities and) local areas have proved to be losers because of GST,” says Milind Mhaske, Director of the Praja Foundation, a non-profit organisation working towards accountable civic governance. Instead of relying on the state’s largesse in the form of grants, “there should have been a provision for local areas and cities to receive a share of GST like the state,” he says.

In such a scenario what BMC is left with, Abhay Pethe, professor of Economics at Mumbai University says, is “the property tax”.

But BMC’s collection of property tax has been inadequate. From a target of Rs 5,200 crore in 2016-17 and 2017-18, the corporation collected Rs 4,477 crore and Rs 5,087, respectively.

The reasons for poor property tax collection are attributed to lack of capacity, changes in the method of calculating property tax, as well as political promises of foregoing taxes for apartments smaller than 500 sq ft.

Now, due to the pandemic, the government has allowed a moratorium and tax breaks. Smacked by this liquidity crunch, the civic body has tapped into its humongous fixed deposits.

But not all of the fixed deposit money is available as emergency relief, nor should it be spent carelessly. “A large chunk of it is out-of-bounds as it is earmarked for pensions and other expenses,” Professor Pethe says.

Huge budgets, but not enough

All too often, BMC’s news-making elephantine budget drops focus from the densely-populated peninsular city’s unique needs. “The MCGM or for that matter any other municipality in India does not do a long term and medium term estimate of its funding requirements to meet basic needs of all their citizens. Therefore just by looking at their budget size or deposits, we really cant say they are adequately funded” Srikanth Viswanathan, Chief Executive Officer, Janaagraha Centre for Citizenship and Democracy, says. “The only reason we’re able to say that MCGM is stronger is on a relative basis to other urban local bodies, and not necessarily for its own needs.”

Civic bodies can raise more money from the market if they have a higher creditworthiness and higher autonomy. But municipalities and municipal corporations across India are dependent on states for funding and decision making. This is despite the 74th constitutional amendment which aimed at giving local governments the constitutional validity of the third tier government and devolving powers to them.

The Mumbai civic body might be an outlier because it is relatively more empowered, but it still doesn’t have as much power as it should. For instance, Maharashtra’s implementation of the 74th amendment passed on more essential functions down to the urban local body than other states. But “the city doesn’t have the power to set or revise its own taxes,” Mhaske says.

A revision in taxes, a major source of corporation revenue, may be essential for a government facing revenue shortages but is it essential for a civic body that repeatedly fails to utilise its entire budget?

The approach cannot be one-sided but supported by measures that increase government capacity to run and complete useful projects as well as trigger financial accountability. BMC fails to utilise its entire budget due to a leadership failure, Mhaske says, but it still needs to raise more money to provide better services.

“Revising or introducing taxes is not just a way to increase income but also to initiate better town planning,” he adds.

In the next article, we will explore alternate ways to raise funds and augment financial management.