It came and went without much hooha. World Mountain Day on December 11th. And its theme for this year, “Sustainable tourism”. It was an apt theme that the UN chose. But it also exposed the limited understanding of mountains in the larger context.

Mountains across the world, including our own Himalayas, attract a large number of tourists. But considering them as just hotspots for sustainable tourism is not the right approach. These mountains are actually large ecosystems so profound in the sustainability of our existence.

The Himalayas provide abundant proof of this. The lives of millions of people depend on these ecosystems. Not just preserving them, but the restitution of nature itself is urgently needed.

Why the Himalayas are important

The Himalayas span five countries: Bhutan, India, Nepal, China and Pakistan. It covers 2,500 km running west-northwest to east-southeast in an arc. The Himalayan range is bordered on the northwest by the Karakoram and the Hindu Kush ranges, on the north by the Tibetan Plateau, and on the south by the Indo-Gangetic Plain.

Some of the world’s major rivers, the Indus, the Ganges, and the Tsangpo–Brahmaputra, rise in the vicinity of the Himalayas, and their combined drainage basin is home to some 600 million people with 53 million people living in the Himalayan regions.

The Himalayan mountain ranges contain 60,000 km² of ice – storing more water than only the Arctic and Antarctic.

Read more: What’s causing climate risks in our smaller cities and towns?

Almost 33% of the country’s thermal electricity and 52% of its hydropower is dependent on river waters originating in the Himalayas. These rivers receive a significant part of their water from the melting of glaciers, making them a critical component of India’s energy security. And its water security needs.

The Himalayas also play a role in sustaining the monsoon. The Tibetan plateau heats up in the summers creating a low-pressure area that leads to southwest monsoon winds coming to the Indian subcontinent. It also modifies the route of the winds. In the east, the winds turn along the mountains in the northeast, and move along the Brahmaputra-Ganges plains distributing rainfall.

The impact of climate change is evident in this region today in the changing precipitation patterns and melting of its glaciers. Glaciers in the Himalayas lost billions of tons of ice between 2000 and 2016, double the amount that took place between 1975 and 2000, as per studies. Which also show a surplus in its river waters by 3-4% due to a 10% increase in the melting of glaciers of the western Himalayas, and the 30% increase in the eastern Himalayan glaciers.

All these facts only highlight how and why the mountains are indispensable and the urgent need for their restitution. Unfortunately, our mountains are treated only as tourist destinations without realising that over draining resources beyond a point can be disastrous.

Read more: What lies behind the deepening water crisis in Himalayan towns?

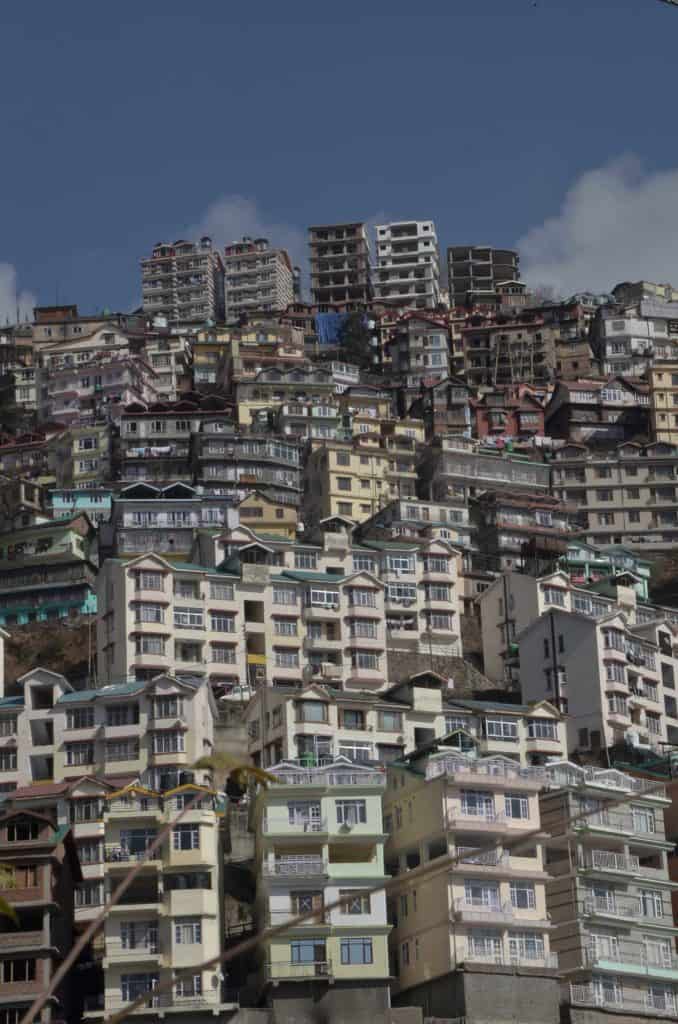

The theme of sustainable tourism may sound good, but the sustainability of mountains as an ecosystem must be revisited. Especially in the Himalayas and the hill towns like Shimla, Mussoorie and Dalhousie built by the British.

It is totally wrong to say that British engineering and technology skills sustained the mountains. The fact is local communities before the advent of the British to the mountains never built structures or lived on the ‘ridges’ and hilltops. It is the British who did this with their hill towns.

What Shimla and Leh can teach us

The British taught us how to ruin the mountains, but in a sustainable form. Take for example Shimla, the erstwhile capital of colonial India. This is quite an intriguing town for urban planners. The water supply to the town initially was ensured from nearby water catchment areas like Seog forests, which was piped using the pull of gravity, from the forest springs to the town. Later, a lift water scheme was installed as the population grew. This scheme from Gumma had an elevation of nearly 2,000 metres to pump water which was then distributed in the town.

The British could sustain such a system because of its imperial loot. But the high operation and maintenance costs of these systems has made it impossible for today’s urban local bodies to run such a system without heavy state subsidies.

Take another example, Leh town, which over the last few years has seen a large influx of tourists. Shimla with a population of two lakh gets more than 4.5 million tourists. Whereas Leh with a population of just 30,000 had nearly 10 times more tourists.

It is for sure a source of livelihood for many people. But the land-use change and change in the pattern of employment also needs to be studied closely.

Why? For the simple reason that Leh town, which used to consume drinking water from the natural source of water flowing from the glacier and underground bores, can no longer do so. The water is today unfit for drinking due to the shift from dry toilets to wet flush toilets for tourists, which has contaminated the ground water. This is not sustainable tourism.

Read more: Yet another plan to regulate traffic in Shimla, but will it work?

There are a few important lessons to be learnt from just these two towns to ensure that the least damage is done to the mountains and especially to the Himalayas.

- The first: The rampant construction of hydropower projects without any concern for the ecology must stop. The mighty Sutlej river, from the point it enters India, is being conduited through the mountains till it joins Bhakra Dam in Bilaspur. Other projects either commissioned or in the pipeline include, to name a few, right from Khab, its Khab Shaso, then Jangi Thopan-Powari, followed by Shongthong Karcham, Wangtoo Karcham, Nathpa Jhakri, Rampur, Behna, Kol Dam and finally the Bhakra. Then there are projects being commissioned on tributaries of Sutlej and other rivers. This is the design in almost all the mountain states. The result: Massive change in ecology and environment. And the damage is irreversible.

- The second important intervention relates to the nature of land-use change and the building typologies in urban towns on the mountains. Hardly any mountain town has a statutory master plan. Most planners designing mountain towns bring the formula of the plains and try to implement them there.

Take for example the rampant use of reinforced cement and concrete in construction of houses and a complete paranoia for using timber on the pretext of saving forests, even though it is a proven fact that houses in the mountains must be built with indigenous material including wood for reducing the carbon footprint. However, one finds exactly the reverse happening with massive use of steel and concrete. This further increases the vulnerability of the load-bearing capacity of the mountains.

- Mobility is another important area that must be developed in accordance with the mountains. It means that instead of these Char Dham roads, massive four-laning and widening of existing roads, alternative modes of mobility must be adopted. Ropeways and internal railways through tunnelling, that do not depend on just fossil fuels, can be one major mobility alternative. For the towns, it is important that they continue to harp on the best practices of more pedestrianisation and clean public transport. What is currently being witnessed in these towns is massive traffic jams on the roads and hardly any parking spaces.

- Fourthly, for sustainable tourism, focus should be on developing more home stays, by building capacities of local people, building tourist houses in sustainable mode (solar, local earthen material, water harvesting, local treatment of waste etc.), training people to ensure there is adequate disposal of waste.

- Managing garbage in mountain towns is a big challenge. Since temperatures for nearly six months remains low, hardly any composting takes place. Besides, waste collection, segregation and treatment is very poor in these towns. Waste dumping sites have become an eyesore in these mountains. Bomb Guard is a site in Leh which is one of the worst waste dumping sites and requires immediate attention. Likewise, most hill towns are grappling with waste treatment. With the opening of the Rohtang Tunnel, the access to Lahaul and Spiti is for a longer period in a year. The resultant huge influx of tourists means more waste generation. This has to be taken care of, else the clear rivers flowing in the higher reaches will soon witness irreversible changes.

Given all this, this pledge of “Sustainable Tourism” will be meaningless unless the mountains are sustained as an ecosystem. Restitution and not restoration should be the slogan.

For long term susustainable development of the hills

1. Water supply

2. Garbage disposal

3. Employment other than tourism which adversely affects 1 and 2