Every summer, Bengaluru’s water crisis makes headlines; tanker prices soar, lakes dry up, and citizens protest encroachments, fish kills, and sewage inflows. While lakes and tanks often dominate the conversation, there’s another hidden system that quietly shapes the city’s water story: stormwater drains (SWDs).

These drains are more than just channels; they are the veins of a valley city. Bengaluru sits on a central ridgeline that naturally divides its water flow into two directions:

- Eastward: draining into the Dakshina Pinakini (Ponnaiyar) River.

- Westward: draining into the Cauvery Basin via the Vrishabhavathi River.

Ironically, what citizens often see as footpaths or pedestrian shortcuts are actually parts of this drainage network—an infrastructure that has been neglected, misused, and misunderstood.

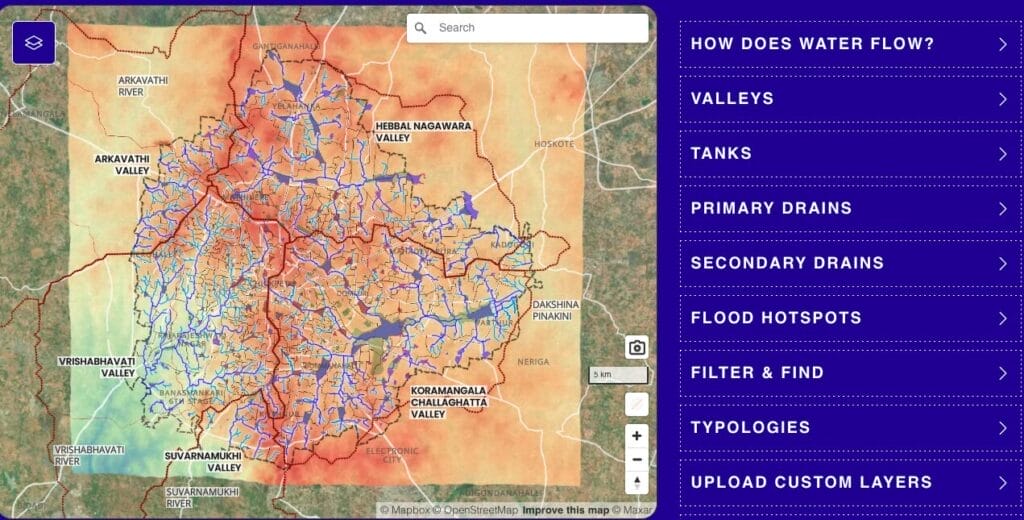

Bengaluru’s topography and drainage system

Bengaluru’s landscape is a patchwork of highs and lows. These “ups and downs” form natural valleys that act as collectors of rainwater runoff:

- The central ridgeline: Splits the city’s watersheds east and west.

- Valley systems: Examples like the Koramangala–Challaghatta Valley show how lower-lying areas gather water from surrounding slopes.

- Watershed dynamics:

- Steeper gradients = faster water flow.

- Larger catchments = higher volumes.

- Historically, cascading tanks and wells managed this flow in a balanced, sustainable way.

Stormwater travels from rooftops, gardens, and roads into roadside drains, then into larger valley drains, eventually reaching lakes and rivers.

This system is managed by approximately 840 kilometres of stormwater drains, categorised into:

- Primary drains (Rajakaluves): The largest main canals.

- Secondary drains: Feeder channels to the primary drains.

- Tertiary/Roadside Drains: Local channels collecting water from streets and neighborhoods.

This hierarchy was designed to move water efficiently across the city’s varied terrain, connecting everyday rainfall to the larger lifelines of rivers and lakes.

Read more: Tracing the K-100 stormwater drain network

Stormwater governance: A maze

Managing Bengaluru’s stormwater drain (SWD) network is less an engineering challenge than a governance one. Overlapping institutions and fragmented mandates blur ownership and accountability, weakening flood preparedness and long-term planning

- Greater Bengaluru Authority (GBA) SWD department: Formal custodian of stormwater drains. Recent institutional changes signal reform, but outcomes remain unclear

- BWSSB: Water management, including wastewater, is under the domain of BWSSB. Decades-old decisions to lay trunk sewer lines inside stormwater drains have created overlapping ownership and maintenance confusion.

- GBA Public Health Department: Handles aspects such as public health, road design, which causes issues such as surface run-off, etc. Rajakaluve encroachment notices and holds property tax data needed to enforce rainwater harvesting, but lacks system-level integration with BWSSB.

- Bengaluru Solid Waste Management Limited (BSWML): Manages solid waste, a major contributor to drain blockages. The volume of waste dumped in SWD is higher than the rest of the city!

- BESCOM and KPTCL: Power utilities with infrastructure along drain corridors.

- Karnataka State Natural Disaster Monitoring Centre (KSNDMC): Flood forecasting and emergency response.

- Karnataka State Pollution Control Board (KSPCB): Water quality monitoring and regulation.

Where governance breaks down

- Jurisdictional mismatch: Natural drainage valleys cut across wards and constituencies.

- Data silos: Incompatible property records stall rainwater harvesting enforcement.

- Lack of clarity: There are no clear guidelines as to the permissible water quality inside SWD and how it is managed and maintained. No clarity on Rainwater harvesting or treated water reuse.

- Limited transparency: Around ₹1,000 crore is spent annually on drain maintenance, with little public disclosure.

- Legal gaps: Despite a 2011 High Court ruling recognising rajakaluves as “critical lifelines,” they continue to be treated as open drains or sewers.

Bengaluru’s stormwater governance sits within the Karnataka Water Resilience Program (KWRP), a state-led effort to restore water systems for climate resilience. But unless the city’s governance maze is untangled, resilience will remain an aspiration rather than an outcome.

[This is the first part of the excerpts from the Masterclass: Citizens & Stormwater — Participatory audits for better cities organised by Oorvani foundation]

Future will be on potable water for every host hold, not just apartment complexes. so STP at every collection points is a must to treat the water and let to next stage.

good initiative