As with Joshimath, the ecological crisis threatening an already sinking Shimla and other hill towns in neighbouring Himachal Pradesh was long foreseen and predicted.

Prof A K Mahajan, a geologist at Central University of Himachal Pradesh, Shahpur (Kangra) undertook a scientific study in 1998 on the twin-towns of Dharamshala and McLeodganj. “There is high similarity in the land subsistence crisis at Joshimath and McLeodganj town,” says Professor Mahajan. “Since 1998, I have been repeatedly highlighting the warning signals relating to the sinking threat at McLeodganj. Recently, when a road, ‘Khara Danda’ connecting Dharamshala with Mcleodganj started sinking, it was a reminder of the happenings at Joshimath. I have tried to draw attention of the authorities through media”.

Apparently with little success.

The Himalayan mountain towns, especially in Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh, seem to be stuck in a tragic cycle — repeated warnings by experts ignored, causing sinking of towns like Joshimath and soon after in Doda in Jammu, and now threatening Dharamshala, Mcleodganj and Shimla. All geologically unsafe and vulnerable to soil subsidence.

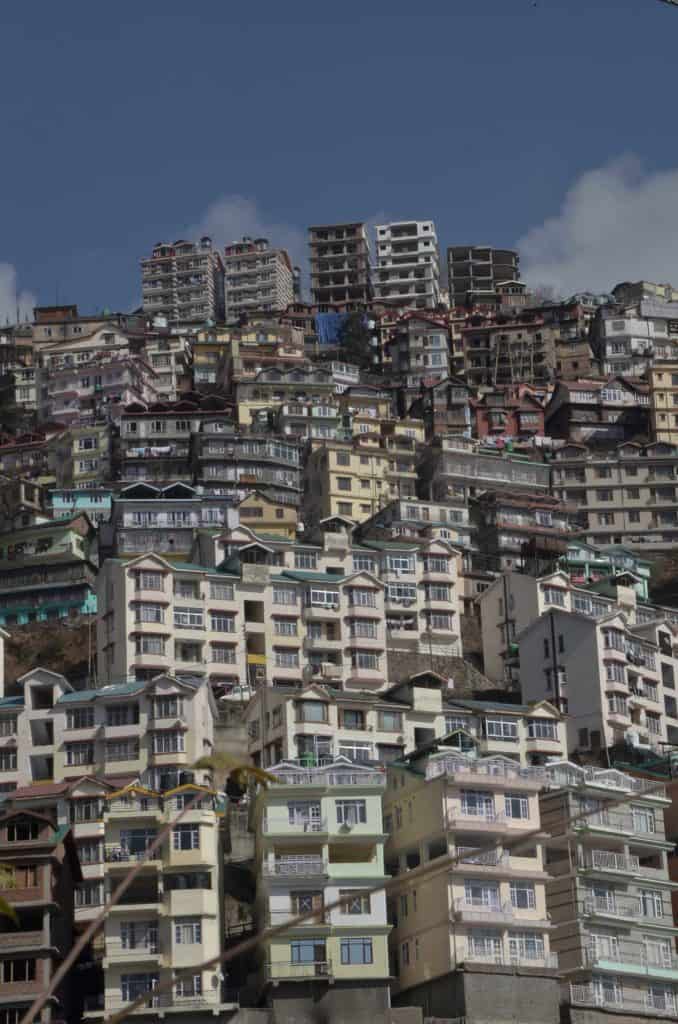

This is one of the side effects of haphazard growth of so many hill towns in Uttarkahand and Himachal Pradesh. In both states, its popular hill towns have far exceeded their carrying capacity and are struggling with faulty drainage systems and ecologically unscientific approach to infrastructure development.

Read more: Joshimath ignored all warnings since 1976; this is what scientists are saying now

Professor Mahajan, who had earlier worked with the Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology, has attributed the soil sinking effect to seepage of water from septic tanks built several years back. The sewage in the septic tanks is a source of soil moisture which, over time, weakens the soil substructure, which led Prof Mahajan to predict sinking in different zones at McLeodganj and Dharamshala.

Both towns do not have any proper sewage disposal system. Some initiatives under “Smart City” project have been taken in Dharamsala. But McLeodganj is yet to see any such measures.

Deputy Commissioner Dr Nipun Jindal was quick to seek a report from Dharamshala Municipal Corporation and Town and Country planning department, asking them to get experts to study the sinking threat and the caving in of road.

“Stability of the town and safety of the population is paramount,” says Dr Jindal. “We will take all precautionary steps once the report reaches my table next week.”

Mcleodganj: A ticking time bomb

Till the arrival of “exiled” Tibetan Spiritual leader Dalai Lama in McLeodganj in 1959, it used to be an oasis of quiet living with little human activity. The overlooking Dhauladhar Ranges, glaciers and cedars was a perfect setting for the exiled community.

Today, McLeodganj, also known as Little Lhasa as the Tibetan Government in exile is headquartered here, is typical of other urban centres in the Himayalan states. A complete urban mess — an ugly combination of hotels, resorts, congested Tibetan markets, restaurants, all built by massive hill cutting and felling of entire forests, unmindful of the damage to the fragile geology of the area.

“The situation today is horrifying to me,” says Virender Paul, professor and head at School of Architecture and Planning, New Delhi. “A time bomb waiting to explode.”

Professor Paul hails from Kangra and is worried about the fate of the town and its inhabitants. He recalls how a flash flood due to heavy monsoon showers in McLeodganj in July ’21 had completely flooded Bhagsu Nag, a sacred waterfall and ancient temple. Homes, hotels, guest houses were all flooded and tourists cars were seen floating in the flood waters.

“It’s because there is no drainage system in place, as people have built concrete structures on storm-water channels,” says Paul. “This is the most dangerous thing to do in a hill town. The continuous seepage of water into the soil overburdened with structures could push the town down-hill any time”.

Yet, even as experts warn that McLeodganj has exceeded its carrying capacity, new construction keeps coming up all the time, many of them in complete violation of the building norms.

Which is why Mahajan favours a total construction ban in all the sliding zones as one of the measures to save Dharamshala and McLeodganj. Both towns also fall in Seismic zone –IV. A major earthquake in Kangra in 1905, measuring 7.8 degree one Richter scale, had left more than 20,000 people dead and toppled most buildings in the towns of Kangra, McLeodganj and Dharamshala.

The scale of the human tragedy if such a quake were to strike the area today is unimaginable!

Experts emphasise that measures to save the sinking of McLeodganj should begin immediately given the recent Joshimath and Doda crisis. Their recommendation: Immediate stoppage of construction and improvements to the town’s drainage system on a war footing.

Some years back, the army, which has a sizable presence in the twin-towns, had written to the Kangra administration suggesting that the movement of heavy vehicles on the main Dharamsala-McLeodganj road be stopped, as it has become a sinking zone. It turned out to be just another warning ignored.

“I am strongly in favour of a complete construction ban in Mcleodganj for at least five years,” says Dharamshala Mayor Onkar Nehria but feels the new government has to take a call on it. “The survival of this world famous town is under threat. Almost every second house in McLeodganj is either a hotel or home stay, mostly unauthorised or illegal”.

But the Mayor is either unable to or unwilling to implement what he admits is a major existential threat to his town.

Dharamshala’s fate

Dharamshala faces all the problems and risks that Mcleodganj faces. With an additional twist. The potential environmental cost in developing Dharamshala as a “Smart City” at a cost of Rs 650 cr,. But there has been public protests either in Dharamshala or Shimla against the mindless constructions, encroachments and heavy vehicular movements.

Not far away from McLeodganj, Shimla, the state’s capital, is also threatened by the sinking from the Ridge, a city landmark, to Kacchi-Ghati, a hotspot of hazardous events. In 2021, an eight story building collapsed at Kacchi–Ghati locality leaving several families homeless.

Experts from IIT Roorkee and National Institute of Engineering (NIT) Hamirpur had then found that the structure was built on unstable and loose soil in the sinking zone at 65 degree elevation. The building had developed cracks due to seepage of water in the foundation. Luckily no lives were lost as the administration had evacuated the building following cracks in the structure.

As a result of this, the Municipal Corporation has decided not to grant any approval to new constructions in the area. Meanwhile, the National Green Tribunal (NGT) has also passed fresh orders against permitting any construction in areas prone to landslides as mildest earthquake could spell a disaster for Shimla.

Shimla’s Ridge, an open space in the middle of the town, had started sinking some years back threatening the town’s mega water storage tank built beneath it by the British. IIT Roorkee experts who studied the reasons for sinking recommended taking up Ridge Stabilisation work by strengthening the critical portion of its foundation rock.

“The Public Works department has started stabilisation work at a cost of Rs 40 crore under supervision of experts from IIT Roorkee” says Ashish Kohli, Commissioner Shimla Municipal Corporation”

The scientific studies by the Roorkee teams have found that the sinking portion was actually a dump of debris but down below it there is a solid rock. To stabilise it, the Municipal Corporation should do an engineering solution, using cement and concrete filling in to be raised from foundation rock structure.

Only last year, the Tibetan market next to the Ridge was shifted to the other side of the cart-road due to sinking. The entire area around the Ridge, between the British era Grand hotel and Lakkar Bazar market, falls in the sinking zone.

Shimla on the brink

In fact, more than 30% of Shimla’s heritage zone falls in the sinking zone. Not surprising, given that Shimla was designed by the British for a population of 25,000, which now exceeds three lakhs. So much so that the town is crumbling under its own weight, as a majority of the buildings are on 60-70 degree slopes.

“The government is the biggest culprit and I say it’s planned (not unplanned) destruction,” says Tikender Singh Parmar, a former Deputy Mayor and urban policy expert. “If today it is Joshimath, tomorrow it could be Shimla, McLeodganj or Reckong Peo (Kinnaur). I have seen Shimla sliding downhill before my eyes. I wonder what will happen if an earthquake hits the town”.

It’s only a year back when two major landslides in Kinnaur killed at least 40 people. Massive blasting, use of tunnel boring machines, explosives and unscientific dumping of mock and debris done by the hydro-power companies on the banks of Sutlej and Baspa rivers have destabilised entire mountain ranges in Kinnaur, known for its rich biodiversity and endangered species like Chilgoza forests.

A retired IAS officer, Avay Shukla had headed a high-power committee set-up by Himachal Pradesh High Court to study the ecological impact of the hydro-power projects on the state’s ecology and rivers. He had recommended a complete ban on all new projects to save endangered rivers including Sutlej, Beas and Ravi.

Read more: Shimla’s haphazard building policy a recipe for climate disaster

Kinnaur’s residents are up in arms against the hydel projects. They coined a slogan “No means No” after witnessing a series of disasters, landslides and sinking of roads, villages and drying up of apple orchards. Construction of underground tunnels for hydro projects has been identified as one of the main reasons for such adverse environmental impact.

Reckong-Peo, the district headquarters, is also showing signs of sinking as there is no drainage system and sewage disposal. Some years back, the local helipad had developed wide cracks. The local Government degree college also faced land subsidence.

Sunder Negi , a young environment activist at Kinnaur, says the government has to stop causing havoc in Kinnaur where mega hydro-projects have been sanctioned without any thought on their negative impact on the region’s ecology.

“We don’t want our fate to be erased as has happened in Joshimath” says Negi.

The earthquake threat

The earthquake in Turkey has raised new concerns mong environmentalists because several hill towns in Himachal Pradesh fall in seismic zone VI and V. The possibility of an earthquake poses huge dangers to towns like Shimla, McLeodganj, Reckong Peo, Manali, Dharamshala, Chamba and Mandi. These are highly vulnerable because of massive constructions, which violates the safety norms and do not have earthquake resistance measures in place.

“Earthquakes don’t kill anyone, but buildings do,” says Anand Sharma, a former Director, Indian Meteorological Centre, Dehradun. “This is our biggest worry for the entire Himalayan region. The people no longer use local materials or follow old building techniques. Structural safety of buildings is compromised. We have seen Kedarnath of 2013 in Uttarakhand or Chamoli disaster, but no lessons have been learnt.”