● With a rise in sea surface temperatures on account of climate change, heavy rainfall

areas extend to greater distances (>300 km) around cyclone centre

● Ocean warming has not only altered SSTs but also their pattern

● El Nino indices (Nino 3.4) have crossed 2°C for the first time since February 2016,

after the super El Nino of 2015

● 2.9 million people in Andhra Pradesh are vulnerable to cyclones as 3.3 million people

are located within 5 km distance from the coastline.

● In the past 40 years, there may not have been a single year when Andhra Pradesh

did not experience either a storm, a cyclone, or heavy rains and floods.

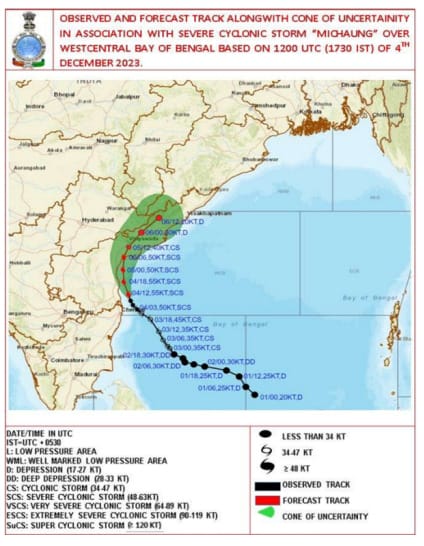

Severe Cyclone Michaung over the Bay of Bengal has caused extremely heavy rains

over the coastal parts of North Tamil Nadu and adjoining South Andhra Pradesh last week.

Torrential and incessant rains have triggered flash flooding in Chennai, which has claimed at

least 22 lives and inundated several streets. After bettering North Tamil Nadu, Michaung made landfall near Bapatla coast, Andhra Pradesh as a severe cyclonic storm.

The proximity of the coast weakened the storm just before the landfall. After that, it recurved north-eastward over land, parallel to the coast. However, even as a weakened depression and low-pressure area, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, and Odisha received moderate to very heavy rains and squally winds.

Michaung is the sixth storm of this year in the Indian seas. December is the peak month of

the post-monsoon cyclone season, where most of the cyclonic storms usually head towards

Tamil Nadu and South Andhra Pradesh. While the formation of a tropical storm in the Bay of

Bengal during December is very timely, the intensity of rains associated with the cyclone

Michaung is not normal.

Climate change multiplies impacts of cyclogenesis

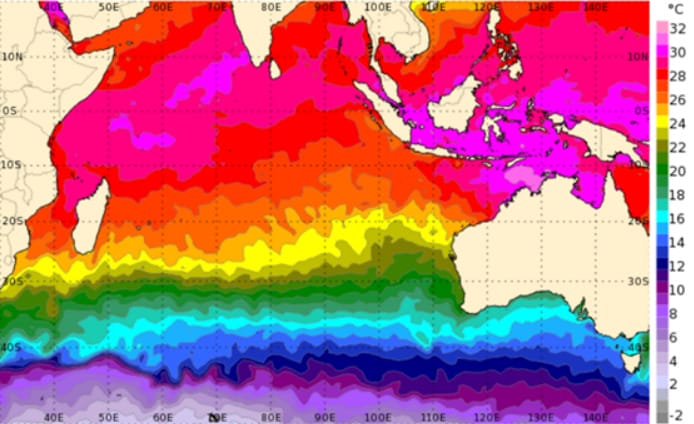

The frequency and intensity of cyclones have increased manifolds, courtesy of global

warming. 93% of the heat is being absorbed by the oceans, and warm waters act as an

energy source for cyclones. Scientists note that the intensity of the cyclone depends not only

on sea surface temperature but, more importantly, on the volume of warm water in the

ocean.

Read more: Anomalies in Chennai weather and link to climate change

According to a report, the increase in sea surface temperature could result in peak heavy

rainfall (>65 mm day−1) in the Tropical Cyclone inner-core region, especially the rear sector.

Heavy rainfall areas extend to greater distances (>300 km) around the tropical cyclone

centre with SST warming. The observed changes of tangential wind speed due to large sea

surface enthalpy fluxes (rate of flow of heat energy) associated with ocean warming result in

Tropical Cyclone size changes and then guide the cyclone to north-eastward movement.

Similar conditions were seen in Chennai, which saw incessant rains on December 3-4 as the

dense cloud bands of cyclone Michaung hovered over the city.

The trio of El Nino, IOD and MJO

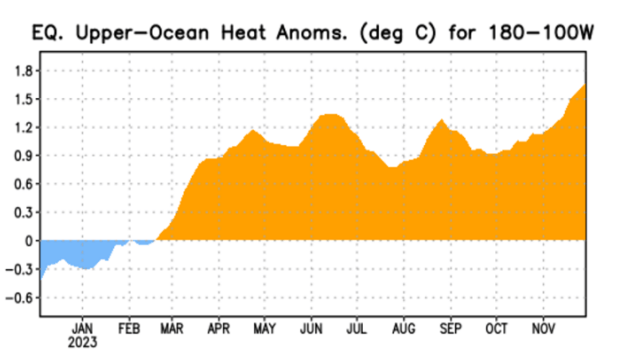

El Nino, since the very beginning, has been in the news for its rapid intensification.

Equatorial Sea Surface Temperatures (SSTs) are above average across the central and

eastern Pacific Ocean. Nino 3.4, the representative of ONI (Oceanic Nino Index), has

crossed 2°C for the first time since February 2016, after the super El Nino of 2015. Chennai

recorded 292 mm of rain on December 2, 2015 (An all-time high record).

El Niño is characterised by a positive ONI greater than or equal to +0.5ºC. However, these

ONI thresholds must be exceeded for at least five consecutive overlapping 3-month

seasons.

“El Niños usually peak around Christmas in December, a reason why they derive their name

from the Spanish term for ‘little boy’. As oceans absorb more than 93% of the additional heat

from global warming, El Niños are also getting stronger. They are not little boys anymore but

monsters of the sea. Changes in ocean-cyclone interactions have emerged in recent

decades in response to Indian Ocean warming and are to be closely monitored with

improved observations since future climate projections demonstrate continued warming of

the Indian Ocean at a rapid pace along with an increase in the intensity of cyclones in this

basin,” said Dr Roxy Mathew Koll, Climate Scientist at the Indian Institute of Tropical

Meteorology.

Meanwhile, other two important oceanic phenomena, the Indian Ocean Dipole and

Madden-Julian Oscillation, both associated with positive rainfall over Indian landmass, were

in favourable zones. These, along with anomalous high sea surface temperatures, provided

conducive dynamic and thermodynamic conditions for the genesis.

How global warming is changing the dynamics of cyclones for India

The large natural variability in a relatively short observational period makes it difficult to

determine what percentage of the observed tropical cyclone activity changes can be

attributed to ocean warming due to forcing by greenhouse gases. It is worth noting that the

impact of SST warming on cyclone activity is not only related to the magnitude of SST change but also associated with the SST change pattern.

Role of SST in the intensification of cyclones: Recent observations indicate that cyclones in

the north Indian Ocean are now exhibiting rapid intensification, intensifying by more than 50

knots in just 24 hours, in response to SSTs much higher than 30°C, prominently due to the

rapid warming in the region. From 2000 onwards, the frequency of cyclones undergoing

rapid intensification in the north Indian Ocean has increased. The percentage of cyclones

undergoing rapid intensification in the north Indian Ocean is higher (38%) than the cyclones

in the northwest Pacific Ocean, where this rate is 22%.

Due to the eastward shift of the cyclogenesis location in the Bay of Bengal, the cyclones are now travelling for a long time over the ocean and drawing more of the thermal energy released from the warm ocean waters, thereby enhancing the chances of developing into a very severe cyclone with

intensity greater than 65 knots.

Ocean heat content: Besides the SST, the ocean heat content also regulates the TC intensity, particularly for slowly moving TCs. The intensity of cyclones in the north Indian Ocean is governed not only by the SSTs but also by the high ocean heat content and warm ocean subsurface. Ocean heat content acts as an essential parameter governing the life cycle and intensity of cyclones in the north Indian Ocean. High ocean heat content implies a warmer upper ocean, which helps cyclones sustain or intensify due to the uninterrupted supply of sensible and latent heat fluxes from the ocean surface to the atmosphere.

Rapid global temperature increase has made cyclone forecasting further challenging.

According to scientists, it is vital to garner critical information associated with ocean warming

to assess the cyclone impact and management and to develop a cyclone-resilient society.

Loss and Damage from cyclones on the East Coast of India

The Bay of Bengal (BoB) accounts for an average of 5–6 cyclones among the world’s

tropical cyclones (TC) each year. Though this is a low number, TCs in the BoB basin result in

a massive death toll compared to other regions. Intense tropical cyclones possess

destructive characteristics attributable to their mighty surface-level winds, extensive

precipitation, and the resulting storm surge. Consequently, they can inflict significant harm

upon agriculture, properties, and livelihoods, resulting in substantial economic losses.

Read more: Does Chennai need a climate action plan?

The Bay of Bengal hosts more cyclones than the Arabian Sea on account of favourable

geographical and atmospheric conditions. Cyclone Fani in 2019 caused an estimated

economic loss amounting to INR 12,000 crores (US$1.6 billion) and damaged more than five

hundred thousand houses within the coastal districts of Orissa. Cyclone Phailin in 2013

caused an approximate economic loss of INR 89,020 million (US $1.16 billion). It has been

estimated that financial loss was nearly INR 8000 crores (US$1.1 billion) during the Odisha

cyclone in 1999.

Cyclone Amphan was yet another powerful cyclone that tore through West Bengal, causing

damage of 1 trillion rupees ($13 billion) to infrastructure and crops.

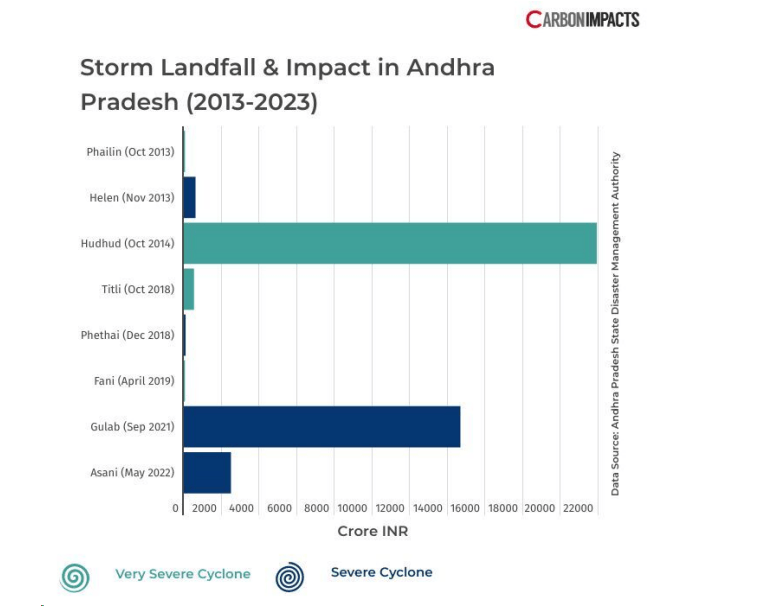

As Andhra Pradesh faced the wrath of Cyclone Michaung, let us look at the history of cyclonic

storms ravaging the southern coastal state. As per IMD, altogether, 184 cyclones of all

categories, including depressions, crossed the coast from 1891 to 2019. The state is at risk

of at least one cyclone each year on an average and maximum during October and

November.

Cyclones with moderate to severe intensity occur every two to three years, which

results in huge damage to the state. According to the state government, 2.9 million people

are vulnerable to cyclones, as 3.3 million people are located within 5 km of the coastline.

Since 1975, the state has faced more than 60 cyclones. In the past 40 years, there may not

have been a single year in which the state did not experience either a storm, a cyclone, or

heavy rains and floods.

[This article is based on a press release by Climate Trends and has been published here with minimal edits. Climate Trends is a research-based consulting and capacity building initiative that aims to

bring greater focus on issues of environment, climate change and sustainable development.

They specialise in developing comprehensive analyses of complex issues to enable effective

decision making in the private and public sector.]

Also read:

- Climate change, warmer oceans could have made Cyclone Nivar more intense

- Sustainability as a solution for climate change in Chennai and beyond