Geared fully in a PPE suit in the harsh Chennai summer, Dr M Keerthi Varman attends to COVID patients at the Stanley Medical College Hospital. Throughout six continuous hours of his duty, he shuttles between the outpatient ward, where he assesses the condition of COVID patients and the ‘zero delay’ ward, where immediate care and oxygen support have to be provided to patients with no time lost in the admission process.

Work in a COVID ward demands more than the usual share of care and alertness. “A patient once removed his oxygen mask to use the restroom. It could have been fatal, had I not been on the rounds and spotted it immediately,” says the doctor.

However, his duties don’t end there. He counsels panic-struck attendants and family members, checks bed availability, helps them with admission, even as he keeps a constant close watch on the emergency cases. The patients who come to the hospital are often among the poorest in society or those with scant knowledge about procedures. After a week of this COVID duty, Keerthi will have to quarantine himself at a government-provided facility for a week before he gets back to work again.

The conditions of work in a COVID ward are no doubt extremely stressful. But it is hardly any better, and sometimes worse, for Dr Harsha (name changed), a doctor working in the non-COVID ward of another government hospital in the city. Harsha gets back to his room only after a 24-hour shift, with his next shift due to start in eight hours and set to continue for another twelve hours. Sometimes, when there are emergency cases, taking a break becomes impossible, so that he ends up working for 36 hours at a stretch. Both Harsha and Keerthi, are Post Graduate (PG) resident doctors who are among the major pillars of healthcare support in government hospitals in the city. Especially now, with the pandemic leading to a huge crunch of manpower resources in these hospitals.

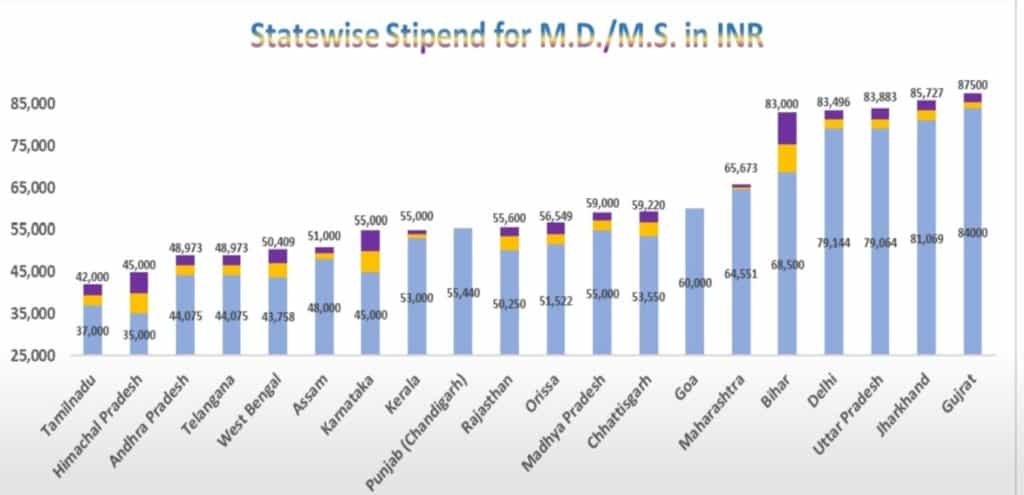

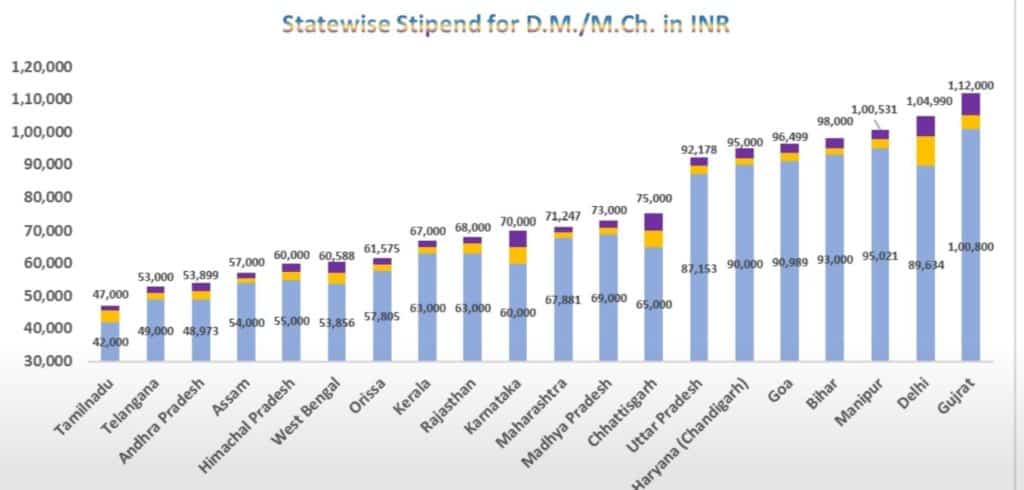

Despite this, they are not even assured of their salary in time. “I am among the 20 resident doctors in Chennai that haven’t been paid since June 2020. Citing a technical glitch, the state government officials promise to clear the pending payment every time we complain. But, sadly they haven’t yet,” said Harsha. Even when they do get salaries on time, PG doctors in Tamil Nadu are the worst paid among their peers across the country.

The pandemic has created new challenges, too. “PPE suits, jumpsuits, coveralls and aprons are often unavailable and we are forced to wear whatever is available, risking exposure to the virus,” wrote the resident doctors from Madras Medical College (MMC) and Rajiv Gandhi Government General Hospital (RGGGH), in a representation made to the Chief Secretary Dr V Irai Anbu IAS earlier this month (May 2021).

Often, these doctors have to function in situations that directly threaten their personal safety. In a recent incident, a caregiver attacked Dr Harsha for no fault of his. “The patient was severely diabetic and had a severe wound, but did not want to get admitted though we strongly suggested that he should. When he came back again with the caregiver, the latter attacked me, accusing us of refusing admission in the earlier instance,” he recalls.

Gruelling schedules, meagre returns

Resident doctors have been working for more than 100 hours a week, translating to more than 14 hours a day on an average, with no off-days, even when there was no extra caseload due to the pandemic. “From admitting patients to handling emergency and toxicology cases, the workload is extremely high for resident doctors on any day. Except perhaps for one lean day in a week, we work tirelessly on the other days,” says Keerthi Varman, who is also President of the Tamil Nadu Medical Students Association (TNMSA), which has around 1000 resident/ PG doctors working in the government hospitals of Chennai.

According to the Tamil Nadu MGR Medical University norms, a PG student can avail 52 days of weekly off and vacation for 23 days in a year, noted TNMSA in a complaint sent to the new Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, M K Stalin. In reality, however, resident doctors function like machines, without a break. Moreover, the tremendous workload coupled with non-medical duties — including facilitation of admissions processes and handling occasional aggression of patient families — sometimes leads them to the brink of depression. “The job can be ruthless and thankless at times,” says Dr Harsha.

Read More: COVID second wave in Chennai: What to do if you test positive

Even according to an order from the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, a PG doctor need not work for more than 48 hours/week and more than 12 hours/day. But for their ceaseless service in the most trying and demanding circumstances, resident doctors in the state are paid a stipend of only Rs 39,000 per month — the least when compared to any state in India.

Voices crying for attention

There are other pressing issues too. “There is no food mess in my hospital; neither do I have the time to cook. At the risk of eating unhealthy, I have to order food every time, which creates an exorbitant food bill for me, often going up to Rs 800 a day,” says Harsha.

For those resident doctors hailing from lower income families, financial dependence on parents is adding to the stress. “My father is a small farmer who struggled to educate me. Now when I should be repaying him, I am still relying on him to pay my monthly bills,” said Vidya (name changed), a PG doctor working at RGGGH. “For the course, we need to spend at least a lakh on books. I can’t even buy them with my own stipend,” added Vidya.

None of the medical colleges in Chennai have couple friendly hostels, forcing married students to rent homes outside the campuses and adding to their financial burden. “That’s the reason I haven’t gotten married yet,” Vidya said.

Considering the increments and DA hike for employees in other government jobs, the stipends of the resident doctors in these government hospitals should annually be increased by 5 to 10%, said Dr Shanthi Ravindranath, Secretary of Chennai’s Doctors’ Association for Social Equality.

Key issues flagged

- Low salary of PG and Compulsory Rotatory Residential Internship (CRRI) doctors working across Tamil Nadu.

- As PPE suits, Jumpsuits coverall and aprons are not always available at the donning rooms, resident doctors are forced to wear whatever is available, with risky exposure to the virus.

- Donning and Doffing facilities are not present in all floors of MMC and RGGGH.

- PG doctors look after the patients in ambulances without any security accompanying them. For the unavailability of beds or delay in admissions, attenders often physically and verbally abuse the resident doctors.

- Resident doctors who test positive for COVID-19 have to wait for hours to get an admission. In some cases, they are asked to quarantine themselves at home.

- Delayed credit of stipend, unavailability of life saving drugs and delay in collecting samples are other issues in government hospitals that they have raised.

Waiting for response

Over a period of ten days this month, TNMSA has met all the stakeholders concerned — Chief Minister M K Stalin, Health Minister Ma Subramanian, Directorate of Medical Education (DME) and Health Secretary J Radhakrishnan. “We thank the officials for lending us an ear and taking our fight in the right stride,” said Keerthi Varman.

“The concerns of the resident doctors will be taken into consideration after ten days,” Health Minister had said. As the 10-day duration promised by the Health Minister ends today (May 25th), the resident doctors are eagerly awaiting some sort of response. “We know there are bigger issues to deal with during the pandemic, we do not expect a government order right away. But, a written statement or a press release would assure us,” said Keerthi Varman.

Health Secretary J Radhakrishnan assured that efforts are being undertaken to increase the stipend. “It is long overdue. We had received many oral complaints earlier and had taken up the issue with the Finance Secretary. The written complaints add weight and we are now taking it up again with the Finance Secretary,” said Health Secretary J Radhakrishnan.

While the TNMSA members have been criticised by some people and a section of the media for campaigning for their rights in the middle of a pandemic, they point out that none of them have let this fight affect their duty. While doctors in other states have been known to go on strike over similar demands in the past, these doctors in Chennai and the state have confined their protest so far to making representations before government officials and launching a social media campaign. The question, however, remains if this will lead to their voices being heard.