Kumari (name changed), a nurse at a reputed government hospital in Chennai has not been able to feed her child for over 10 days now. She had been exclusively breastfeeding her infant boy till weeks back, but these days she has to leave instructions with her husband on what to feed him and the lullabies to sing in her absence. She then leaves for the hospital, only to come home after 14 days.

A lactating mother, Kumari has a tough and choiceless job ahead: 12-hour long shifts for five days at a stretch, attending to COVID-19 positive patients and to be away from the family during those days and for at least nine days after that. While Kumari is busy checking the vitals of the patients and assuring them of speedy recovery, her baby is fed on formula milk.

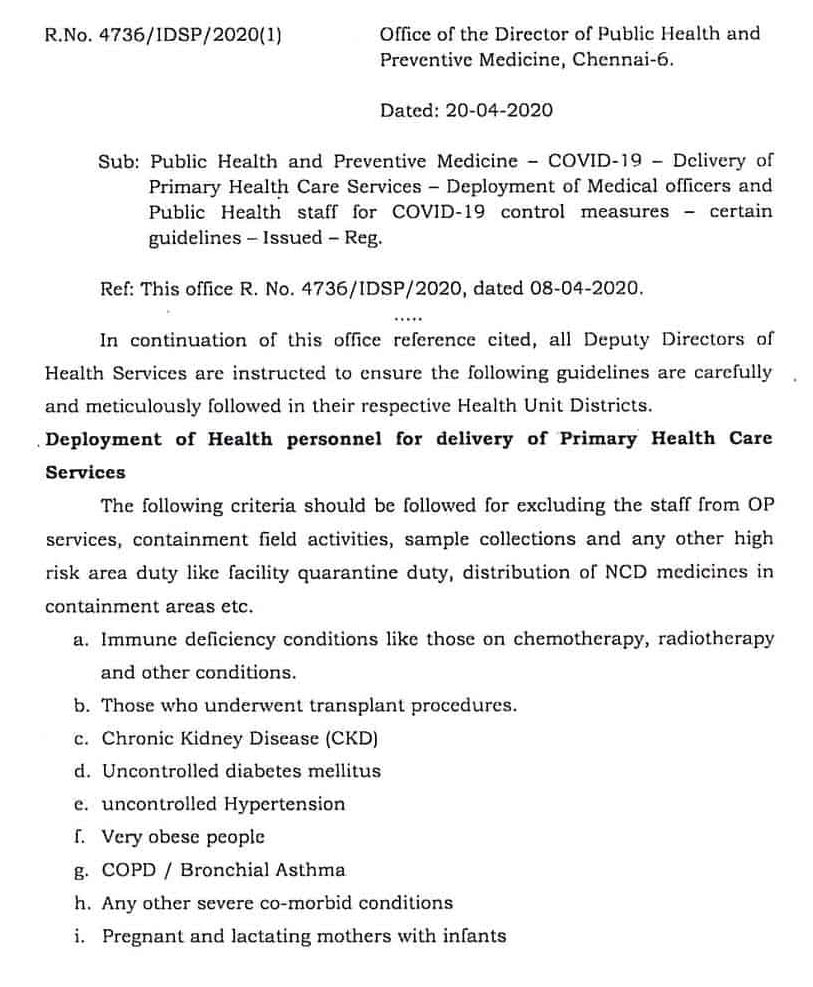

Many nurses share the same plight as Kumari, even though an internal circular from the Department of Public Health and Preventive Medicine (DPH) explicitly mentioned that lactating nurses and those with medical conditions must be excluded from COVID-19 duty.

The shortage of Personalised Protective Equipment (PPE) for healthcare workers is widely known, but less talked about are the overall miserable conditions in which nurses in Chennai are working, as the health infrastructure of the city is overwhelmed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The circular was a nominal affair. Hospital authorities turn down our genuine requests; they say we have to work because there is an employee crunch,” says Kumari. “I am extremely worried about my son. He is too young for formula milk,” she adds, gulping back sobs.

Long hours: Violation of ICMR rules

The individual challenges of nurses like Kumari constitute just the tip of the iceberg, as the community fights a range of issues. With fresh and increasing cases of COVID-19 being reported every day, the state government has recruited 1,323 nurses from the Medical Services Recruitment Board (MRB) and extended the service of retiring nurses (set to retire on March 31st) for two more months. But the question remains whether there are enough healthcare workers to tackle this health crisis. The total number of active cases in Chennai stood at 3,822 on May 18th, excluding discharged patients and fatalities.

For nurses and other paramedical staff, how healthy are their working conditions as they risk their lives to work in the COVID-19 wards? If one looks at working hours alone, nurses in government hospitals are working 12-hour long shifts for five days continuously, which in itself constitutes a violation of the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) rules, according to Dr A R Shanthi, Secretary of Doctor Association for Social Equality.

R Manganayaki works from 7 pm to 7 am at the COVID-19 ward of the Rajiv Gandhi Government General Hospital (RGGGH), attending to patients in the ICU. She doesn’t remove the PPE during the shift, and against protocol removes the mask after six hours of duty to gulp a few drops of water. But she cannot take any breaks for using the toilets.

“We have to remove the whole kit to use the loo. We have no time for that,” says Manganayaki, oblivious to the health risks that these prolonged shifts pose. Nurses taking unduly long shifts at the ward are known to be more vulnerable to physical and mental health issues that include urinary tract infections, breathlessness, anxiety and extreme stress.

After the shift, Manganayaki removes the protective gear, goes to the nurses’ quarters provided by the state government, takes a bath and drinks lots of water. “Thankfully, I have avoided any urinary tract infection till now, But I have developed a severe throat infection,” she added.

They take three shifts on rotational basis: 7 am to 1 pm, 1 pm to 7 pm and the twelve hour night shift: 7 pm to 7 am. After being on duty for five days on such shifts, nurses are quarantined at the government-provided quarters in Saidapet and are sent home only after the swab tests come back negative on the 14th day. They are in home quarantine for five days after that and report to duty again after that.

Experts admit that nurses are being exploited. “According to the National Centre for Disease Control, nurses working during such disease outbreak should work for not more than six hours, seven days at a stretch. The rules are apt considering the fact that these nurses must work with their PPE on, and cannot remove it to use the loo or even drink water. Working for longer hours in a COVID-19 ward is suicidal,” said Dr Shanthi. She added that countries such as China have limited the working hours of healthcare workers to a maximum of four hours at a stretch.

Worker crunch

A nurse finishes the shift at RGGGH. Pic: Laasya Shekhar

At the root of it all lies a major staff shortage in Chennai’s government hospitals, as these conversations indicate. With healthcare workers threatened to keep quiet (to hide the irregularities), it is tough to source authentic information. However, if you ask any nurse how many patients they attend to on an average day, the numbers that emerge are alarming.

Only two nurses (per shift) attend to 26 patients in the COVID-19 ward of the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (IOG), Egmore. What is unique here is that all the 26 patients are mothers who have just delivered babies. “The job is not easy here, as we have to ensure that the newborn babies do not contract the virus from their mothers,” says a nurse, on condition of anonymity.

At the Rajiv Gandhi Government General Hospital (RGGGH), as more wings are converted into COVID-19 wards, the burden eventually falls on the nurses. “I was caring for 20 patients during my shifts last month. Today, I have to look after at least 40 patients a day,” says C Suganthi, a nurse at the RGGGH.

A team of therapists are in touch with the nurses during the quarantine period to help them sail through the crisis. But Kumari finds little consolation. “I am consumed by guilt for not being a good mother. If only they would excuse me from COVID duty…” she trails off.

Neither the health secretary nor the director of DPH could be reached for their comments on the scenario. However, former director of DPH, K Kolandaswamy shared some important facts. “We have been emphasising appointment of healthy nurses with no co-morbid conditions, for attending to COVID patients. Regardless of the amount of protection we provide for nurses, the virus is bound to spread to an extent. The ability of the virus to spread is quite high, and the recommended quarantine period also changes from time to time. In the beginning, a 28-day quarantine was suggested that was later reduced to 14 days, after factoring in logistics, clinical conditions and resources,” he said.

Oh my God. Did not even imagine there were so many problems in Covid-nursing apart from, of course, the danger of contracting the disease itself. My heart goes out to all these nurses, especially the lactating mother who has been unable to feed her baby. What a sacrifice ! May God bless them all and their families too.