Ramakrishna has been a well-digger for thirty eight years. “My grandfather used to dig large stone wells in the villages. In the city, wells are smaller because there isn’t that much space. I learned how to dig wells from my father. I have dug many wells, some are five feet deep, others in higher areas are 18 feet deep or even deeper.” Shankar, another well-digger, has been working since he was 15. “I learnt to dig wells from my father, and now I work with a group of well-diggers. I’ve dug wells all over the city.” Both Ramakrishna and Shankar begin naming neighbourhoods across the city: Koramangala, Malleswaram, Srirampura, Rajajinagar, Dollars Colony… they are very familiar with the groundwater landscape of Bengaluru city.

Well-diggers like Ramakrishna and Shankar are custodians of highly-skilled traditional knowledge that is passed down from one generation to another. In Bengaluru, their community, the Bhovi or the Waddar, were regularly sought after for their skills up until a few decades ago, when borewells slowly began replacing open wells. “Earlier we used to get a lot of work, in the past 15 to 18 years, the demand for well-digging has dropped,” Ramakrishna tells us. When the well-diggers lost their primary livelihood, many of them felt that they had also lost their self-respect.

In the years since, Ramakrishna’s livelihood has evaporated along with the water in Bengaluru’s shallow aquifer zone. This layer, just below the topsoil, works like a sponge to soak up water that percolates down from the ground. Bengaluru sits on the rocky Deccan Plateau. Without a river or a coastline nearby, the city has long relied on water from its wells and tanks (man-made lakes), many of which are centuries old. But the city’s water utility has not been able to keep up with Bengaluru’s rapid growth, and groundwater has been widely used to make up for the shortfall.

“The shallow aquifer sits at the most precipitous interface in the water cycle, the interface of rivers, lakes, snow cover, glaciers, and the immediate subsurface below the soil,” says Dr Himanshu Kulkarni, a senior hydrogeologist from the Advanced Centre for Water Resources Development and Management (ACWADAM). “The shallow aquifer is particularly vulnerable because it has an invisible and often complicated interface with all the other elements of the water cycle, and at the same time it is the most used and misused sub system of the cycle.”

Bengaluru’s man-made tanks

During Bengaluru’s construction in the 16th century, an extensive network of interconnected man-made tanks was dug to cater to the city’s water needs through the shallow aquifer. By 1876, official documents note that the city had 2,300 tanks, 16,725 open wells, and 354 canals. One can imagine the city then, far smaller geographically than the sprawling megapolis it is today, dotted with water features everywhere. Traditionally, these tanks have served two roles: as reservoirs for irrigation and to recharge the shallow aquifer.

Read more: Averting Day Zero: How Bengaluru should manage its water

Increase in groundwater extraction

Since the introduction of borewells (that make it easy to tap into deeper aquifers, below the weathered zone in a impervious layer of fractured rock where water is held within narrow cracks and fissures) for domestic use in the early 1980s, the extraction of groundwater has been steadily increasing and has been largely unregulated. Today, Bengaluru is home to 13 million people and water is now sourced from the Cauvery River from a hundred kilometres away, and it is pumped up an incline of 540 metres.

Water extraction outpaces recharge

Every time a house is built in the city, a borewell is first dug on the land. Now, there are millions of private borewells in the city and their unchecked use has led to Bengaluru’s deep aquifer levels dropping to alarming levels. In many parts of the city, borewells are beginning to run dry. The city’s water extraction has also outpaced its ability to recharge it. Around 700 million litres of groundwater a day is extracted in Bengaluru, but only around the equivalent of 100 million litres a day is recharged.

All this has profoundly changed the relationship people have with their water. The habit of using shallow water sources such as open wells has slowly receded from memory. Many of the wells and tanks have shrunk or have been built over or polluted by rapid urbanisation. From having an open well in the yard and watching its water level rise and fall with the seasons, water has become invisible, it flows from a tap, and the link between the precious resource and its source – the well, the river, or the lake has been severed.

Biome’s Million Wells Campaign

Biome Environmental Trust is a local civil society organisation that has been at the forefront of urban groundwater management for 13 years. They have been active as a community collective advocating for sustainable water management for much longer, since 2002. They work closely with the city’s many different communities to inculcate a sustainable water culture — one where the citizens become stewards of their shared natural resources.

Shubha Ramachandran from Biome explains further, “We work closely with citizens in a number of ways: by translating existing scientific information into layman’s language where it makes sense to people; by translating regulations so that people understand them; providing case studies and stories of other neighbourhoods that have managed to adopt better water management practices; and finally, most critically, connecting them to the people who can help them implement the solutions effectively.”

Since 2015, Biome has been running an ecological literacy campaign called the Million Wells Campaign (MWC). The idea of digging a million recharge wells is a rallying cry, a groundwater campaign about revaluing the shallow aquifer, encouraging citizens to take responsibility for managing and conserving groundwater collectively.

How does one go about reviving a shallow aquifer?

The first step is in making the open well visible, so that citizens begin to see it once again as a viable source of water and recognise the interconnected nature of our water systems. It starts with digging a “recharge” well and directing clean rainwater that runs off into it, which in turn fills up the shallow aquifer. Shubha Ramachandran adds, “We locate the wells in areas where there is a lot of run-off, or where there is flooding or pooling of water, so that the water that then collects is allowed to percolate into the ground through the recharge well. This is how we go about reviving the shallow aquifer.”

The fundamental challenge the campaign has faced is that of the ‘illiteracy’ around water, and Biome has run an extensive communication campaign to build awareness, educate, and help citizens change their behaviours around water usage. “Given the magnitude of the water crisis that India is facing, this campaign has been able to catalyse action around groundwater management in a very focused manner, by making visible a resource and elevating the shallow aquifer in the minds of citizens,” says Dr Kulkarni from the ACWADAM.

Read more: The story of Thippagondanahalli Dam on the Arkavathi

Citizens take the initiative to dig wells

Over the past seven years, the campaign has successfully built this sense of collective ownership over the shallow aquifer. Many communities have set their own targets for building wells, such as in the bustling middle-class neighbourhood of Bellandur, where a federation of resident welfare associations have embraced this campaign and set their own targets of digging 2,500 wells. More than 200,000 recharge wells have been dug in the city. Raghuram Giridhar is a resident from Vidyaranyapura, in north Bengaluru. He built an open well on his property in 2018 and hit clean water at 12 feet, in a neighbourhood where borewells can go as deep as 600 feet in search of groundwater.

“The idea that people can be a part of the solution is not seen as part of the solution for water management. We instead look for big infrastructure solutions,” says Srikantaiah Vishwanath, a trustee at Biome Environmental Trust.

Integrating the traditional knowledge of the well-digger communities

The campaign has also focused on the livelihoods of marginalised communities. The well-digger communities are typically not seen as valuable contributors, and their presence is often limited to the physical aspect of providing labour. The Million Wells Campaign has integrated their traditional knowledge and skills into the process of open well revival. Many well-diggers now have a deep understanding of recharge wells and rainwater harvesting and are able to play an important role in shallow aquifer revival. Consequently, the livelihoods — and self-worth — of many well-diggers like Ramakrishna have been restored. The well-diggers have renewed pride in their work, as they reap the benefits of their renewed economic and social capital.

Perhaps, the most needed aspect of modern urban water education the world over is an appreciation of the shallow aquifer. Dr Kulkarni adds, “If the revival of the shallow aquifer is carefully curated, it can have tremendous impact from flood and drought mitigation, to improving water security in urban India, and responding to the water quality issues that cities often grapple with.“

The Million Wells campaign has been scaled up to other cities. The idea has been picked up by the government scheme ‘AMRUT’ or the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation and will be rolled out in 500 towns and cities across India with an initial investment in 10 towns and cities as a pilot. However, Dr Kulkarni cautions that it needs to be contextually adapted so that citizens appreciate the deeper philosophy behind digging ‘a million wells’. The campaign should retain its demand-driven essence, responding to a collective demand with a scientific sensitivity that incorporates an ecosystem approach. It should retain the value it places on traditional livelihoods and working with communities to revive and support traditional knowledge.

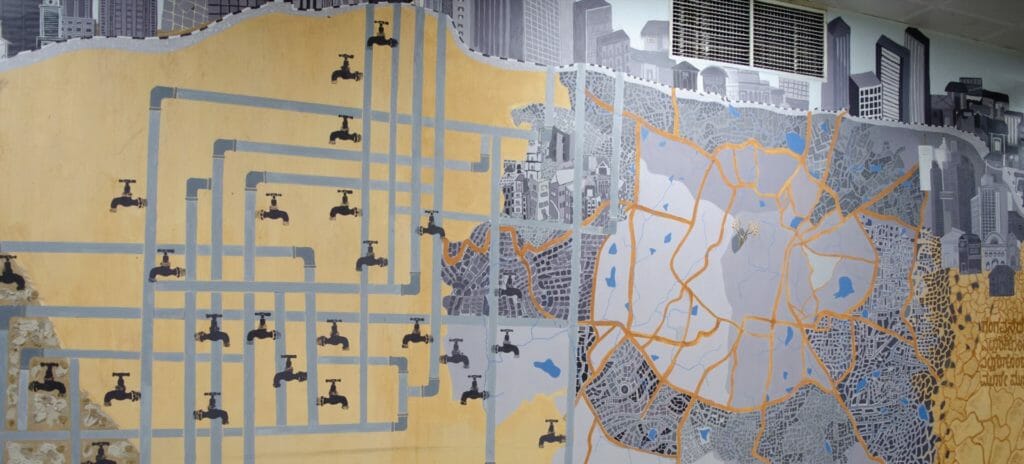

A mural dedicated to the well-digger communities

Bengaluru’s campaign has brought the open well back into public imagination rather innovatively. Recently, Biome worked with the Srishti Manipal Institute of Art, Design and Technology and the local artist community to dedicate a mural on the wall of the Cubbon Park metro-rail station to the story of the city’s groundwater. The mural is painted using mud extracted from wells that were dug in Cubbon Park and prominently features the stories of the city’s well-diggers. For well-diggers like Ramakrishna, it is a small but visible recognition of their contribution to the city: “Biome and the campaign has really helped many of us in the community find our livelihood again. The mural has used different kinds of mud, from the wells we have dug, and I feel very connected to it.”

India has had a long history of wells, and the campaign is perhaps a way for the country to reclaim this knowledge and share it again with the world: what open wells are, what they have given us, and what they can give us again.

[Million Wells for Bengaluru is one of 12 inspiring stories of local transformation, shortlisted for the 2022 Transformative Cities People’s Choice Award. Transformative Cities is a global process to search and support transformative practices and responses that are tackling global crises at the local level. You can still vote for the initiative that you find deserves more attention and resources to scale up until the 6th of November at: https://transformativecities.org.The Transformative Cities Initiative, hosted by the Transnational Institute, provided research and reporting support for this article.]

Unfortunately, most of the shallow groundwater in Bangalore is polluted and unfit for drinking. Instead of shallow wells, we should have sunken gardens and sunken playgrounds. They will recharge the groundwater much better.

How Do I Connect For Digging Wells at My Farmhouse in The outskirts Of Bangalore