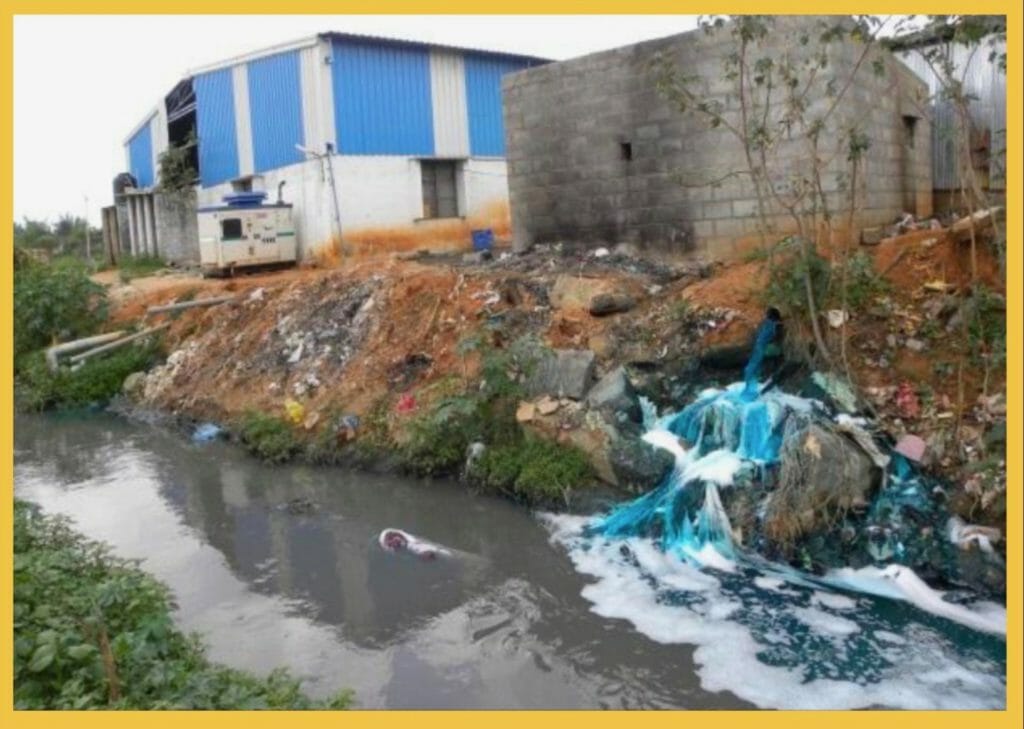

River Cauvery is the lifeline of Bengaluru’s economy. But before Cauvery, it was the Arkavathi. Polluted and now running almost dry for around half a century, Arkavathi is biologically dead. It stands as living proof of what is to come for Cauvery. A victim of urban-industrial society, Arkavathi today is a shadowy semblance of a former glorious river. It is a ghost river.

This is the story of how the Thippagondanahalli Dam and Thippagondanahalli Reservoir, also known as Chamaraja Sagara, on the Arkavathi river rose to prominence as Bengaluru’s drinking water source and 80 years later, became defunct because of pollution and loss of natural river flow. This is also the story of how the Arkavathi river, which existed for millennia, was driven to death in the last 100 years.

With Arkavathi’s death, the Thippagondanahalli dam has just stood there as a testament to the wanton destruction of the very river that provided us with precious drinking water and not to mention, the water for economic progress.

The restoration of Thippagondanahalli Dam

While the Arkavathi river’s state of affairs has not changed, Thippagondanahalli Dam has. It is being restored to hold water from Netravathi, a perennial river 280 km away in the fragile western ghats. In essence, the Thippagondanahalli dam switched rivers: From Arkavathi to Netravathi.

This detailed timeline narrative is critical to our understanding of how our handling of rivers has got us perilously close to running out of water. It shows how decisions to over-exploit the already strained rivers like Cauvery emerge.

On the one hand, there is the silent and almost unnoticed death of the Arkavathi river and on the other, a bloodshed-ridden violent claim to Cauvery river water. This story serves as a constant reminder that whatever we have done and are doing, to protect and conserve the rivers, is clearly not enough.

In this article – part 1 of the series, we shall see the historical context of the dam came to be and its slow and steady decline once Bengaluru started looking towards the Cauvery for its drinking water needs. In the second part, we will look at the political developments that sealed its fate and the environmental impact we are seeing the repercussions of.

Read more: Thirsty city tantrums: How Bengaluru’s thirst for water is felt 400 km away

Thippagondanahalli Dam and Chamaraja Sagara

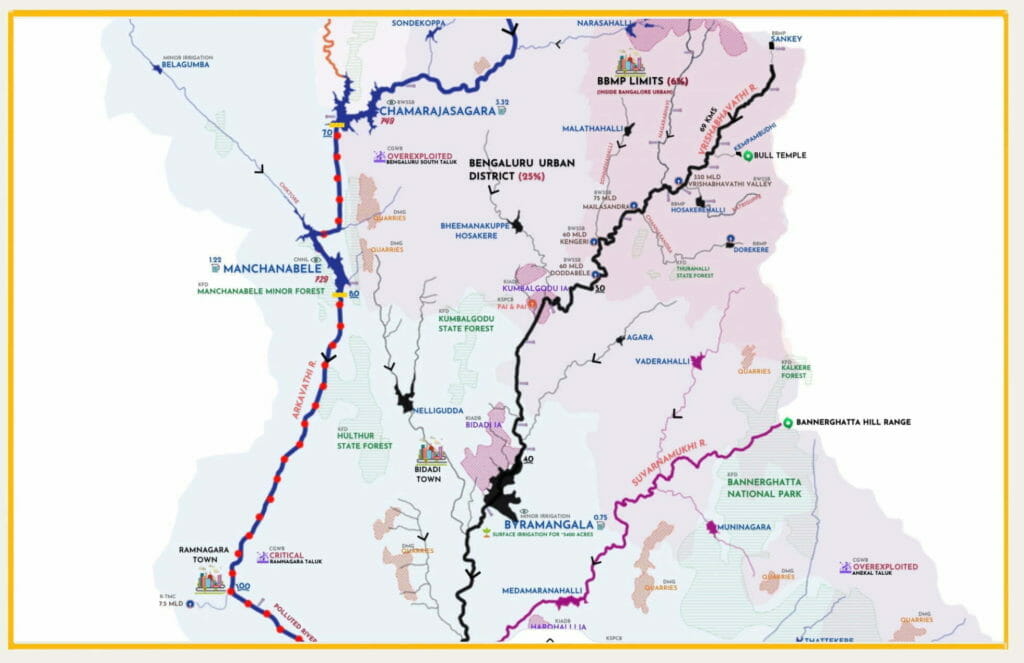

Chamaraja Sagara reservoir is formed by building a dam at Thippagondanahalli, at the confluence of Arkavathi and Kumudvathi rivers, a few kilometres away from the Silicon Valley of India, Bengaluru. Built to serve the drinking water needs of Bengaluru city, the dam can impound 3.3 Thousand Million Cubic-feet (TMC) of water. It is the largest reservoir in the Arkavathi river basin in terms of capacity. It is located in the districts of Bengaluru Urban and Bengaluru Rural.

In operation since 1934, the reservoir went from being Bengaluru’s source of water to Bengaluru’s sink for wastewater. Heavily polluted, the reservoir water is not used for drinking since 2012. Presently, it is being restored to hold 1.7 TMC of Netravathi river water via the Yettinahole Integrated Drinking Water project

“The stream issues from a metal head, formerly it was said to be of silver; the stream is said to be highly reverenced by the Gentoos; it was cool, and flowed in abundance. The number of venerated origins in these hills is a cause of wonder, but so are the many destinations of waters coming off them.”

Colin MaCkenzie describing the source of Arkavathi, Nandi Hills, 1792

Read more: Kaveri and the years of drought

Timeline of Thippagondanahalli Dam and Reservoir

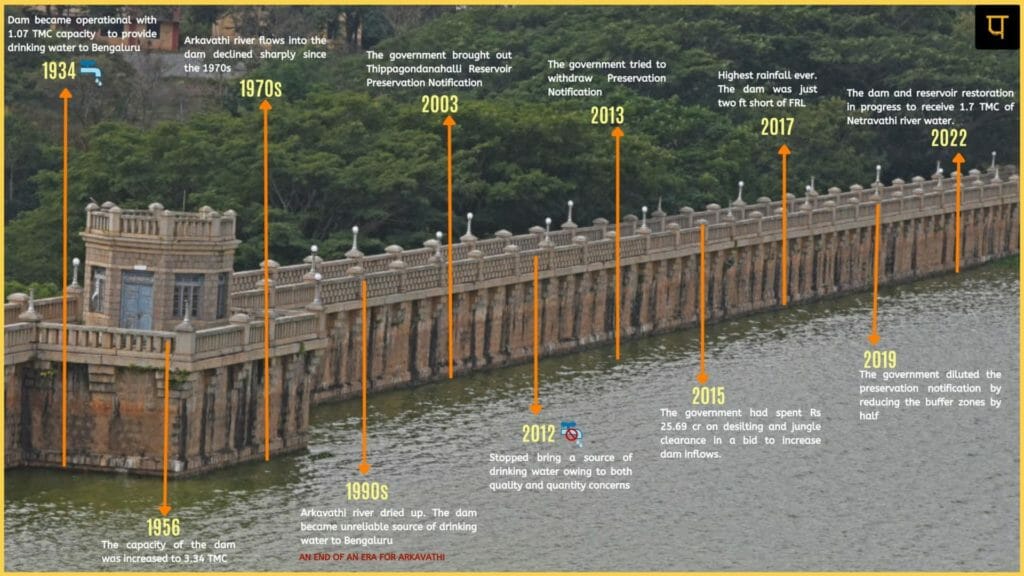

1934: Thippagondanahalli dam became operational

- With the drying up of Hesaraghatta Tank in 1922, and the failure of monsoons in 1925 and 1926, Bengaluru plunged into conditions of severe drought. To augment the dwindling supplies, the Thippagondanahalli Dam was constructed at the confluence of the Arkavathi and Kumudvathi rivers.

- With a capacity of 1.07 Thousand Million Cubic-metres (TMC), the dam had the potential to provide 5 Million Litres per Day (MLD) to the burgeoning industrial city of Bengaluru.

- The total project cost was 50.33 lakhs.

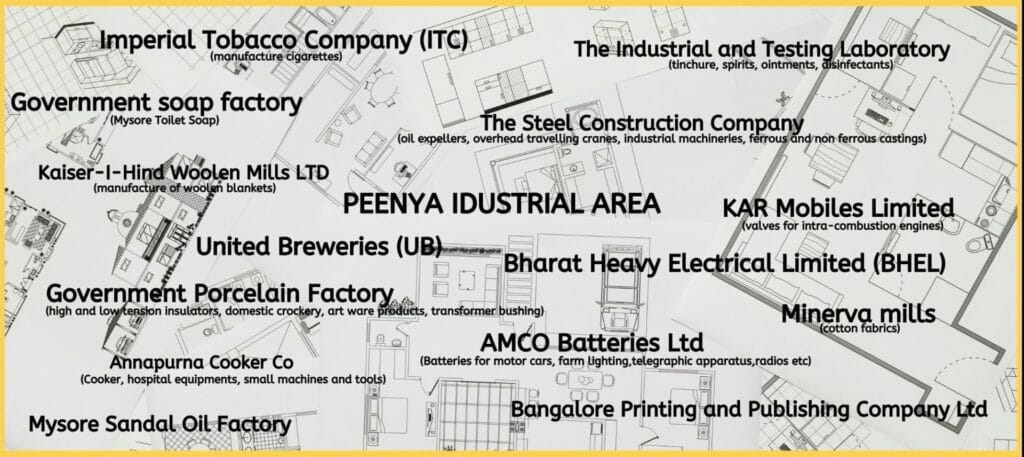

1940s: Industrialisation

- Between 1900-1940s, Bengaluru industrialised heavily. It became home to a large number of private and public sector industries that needed both water and electricity.

- While electricity came from the Cauvery river, water came from Arkavathi. Arkavathi waters harnessed by Thippagondanahalli Dam were critical to Bengaluru’s economic progress.

1950s: Thippagondanahalli Dam height was increased

The height of Thippagondanahalli Dam was raised to 51.82 metres in the latter half of the 1950s, thus increasing the impounding capacity from 1.07 TMC to 3.34 TMC. The dam now had the potential to supply 148 MLD to Bengaluru.

1964: Establishment of BWSSB

The Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB) was established in 1964 for providing water supply and sewerage systems to Bengaluru city. It took over as the custodian of the dam.

1970s: Stage 1 of the Cauvery river water supply

- The dam’s troubles began in the latter half of the 1970s.

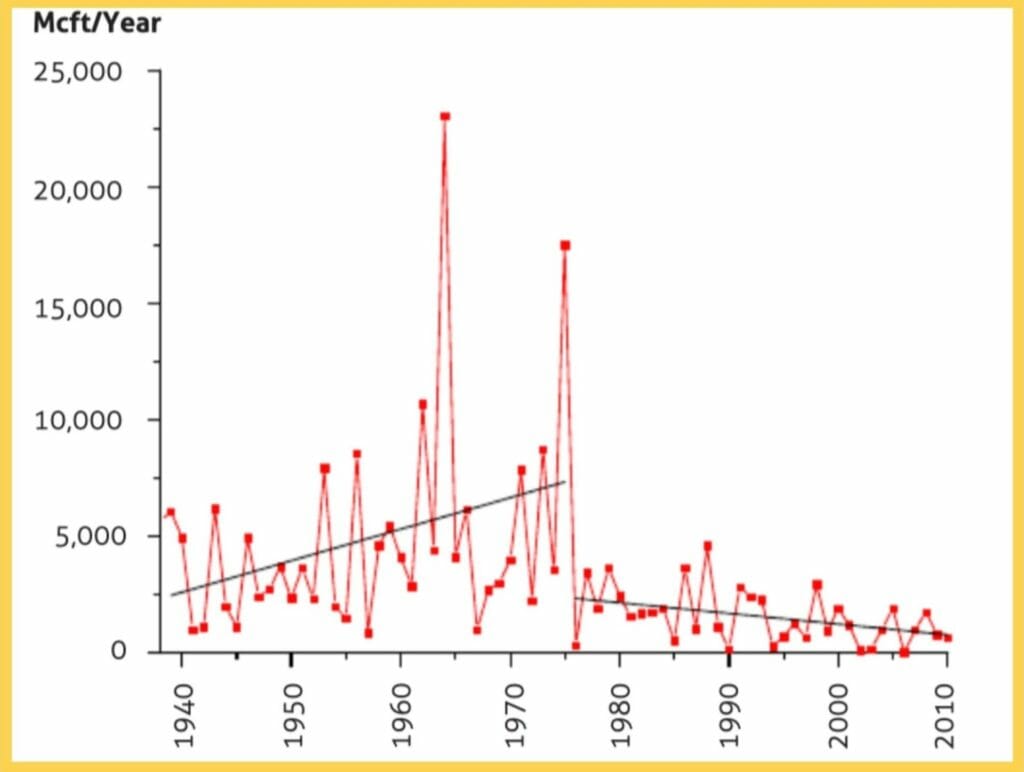

- The flow of the Arkavathi river water into the reservoir decreased by a whopping 83% from 385 MLD pre-1975 to 65 MLD post-2000.

- Around the same time, in 1974, approximately 135 MLD of Cauvery river (Stage I) water was first supplied to Bengaluru.

1979-1999: Real estate agenda versus water security

- The new issue was related to a real estate developer’s agenda vs the water security for the public. In 1979, the District Commissioner (DC) approved a 700-house township, within 2 km of the reservoir. In 1982, alarmed that the reservoir would further deteriorate, BWSSB filed a writ petition in the High Court of Karnataka against the DC’s approval. In 1987, the High court squashed the approvals given to real estate developer, Delhi Land and Finance Universal Ltd (DLF).

- In 1991, DLF revised the proposal by converting the 700-house development into a 200-villa development with a central sewerage system. The state government including BWSSB and Karnataka State Pollution Control Board (KSPCB) approved the revised proposal. This time around, citizen activists filed a Public Interest Litigation challenging the decision. The high court then overturned the state’s approval.

- In 1998, aggrieved by the Karnataka High Court order, DLF approached the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court overturned the Karnataka High Court order, giving permission for the township but the next year, the state government withdrew the permission granted to DLF due to public pressure.

- Meanwhile, the Cauvery river water (Stage II) started to provide an additional 135 MLD, totalling 270 MLD supply to Bengaluru.

1980s: Stage 2 of the Cauvery river water supply

- By the 80s, the dam’s troubles worsened. The reservoir waters became unreliable as a source of drinking water supply, providing less than 25% of what it was meant to. Though, in a one-off event, the dam did fill up to its brim in 1988!

- By 1982, Bengaluru’s Cauvery Supply: Cauvery river water (Stage II) provided an additional 135 MLD, totalling 270 MLD supply to Bengaluru. The loss of Thippagondanahalli waters didn’t really hurt.

1990s: Stage 3 of the Cauvery river water supply

By 1992, Cauvery river water (Stage III) increased by 270 MLD, totalling 540 MLD supply to Bengaluru.

By now, the dam catchment had degraded to such an extreme extent, that by the turn of the century, the river had dried up. What remained was the wastewater flow from Bengaluru city. It was the end of an era for Arkavathi.