This article is part of our special series Environmental Sustainability & Climate Change in Tier II cities supported by Climate Trends.

One of the earliest planned cities in the country, Odisha’s capital even today lacks a comprehensive sewerage system with treatment facilities. As a result, residents of 115 villages living along the lower end of Daya river are afflicted by several diseases, particularly cancer, as they are forced to use its water polluted by effluents and sewage generated by Bhubaneswar’s 11 lakh plus population.

Umakanta Samantray, the MLA from Satyabadi constituency which is about 50km from Bbubaneswar, has been highlighting the problem of the spread of cancer in riverside villages in several meetings he has had with Chief Minister Naveen Pattnaik on this. “During the last three years, there have been five to 10 cancer deaths every two months in these villages,” claims Samantaray.

The smart city tag that state’s capital carries means little for these villagers, whose settlements stretch up to Chilika lake, where the polluted Daya, a branch of the Mahanadi river system, merges with the lake, leading to pollution of that brackish water lagoon too. It is only during the rainy season that Daya looks somewhat clean.

“Pollution of the river has been increasing during the last 10 years,” says Rabindranath Routray of Bankadal village of Pandiakera gram panchayat of Kanas block in Puri district, about 50 kms from Bhubaneswar. “Villagers who bathe in the river end up with skin diseases. Farmers who are using Daya water and its branch Rajua for growing vegetables find leaves turning yellow. Earlier, people were using river water for cooking. But now they use tubewell water despite the presence of fluoride and arsenic in it”.

A government project to provide them piped water from the Mahanadi is now in the works.

The Daya river used to be the main source of drinking water for the district headquarters town of Khurda, near Bhubaneswar and the railway junction town of Jatni (Khurda Road). But because of the river’s pollution, both these towns are now dependent on the Mahanadi water, said a senior water supply engineer.

Bhubaneswar city is surrounded by rivers and reserve forests. The Chandaka reserve forest, now an elephant sanctuary, is on its western side while the Kuakhai river forms the city’s northern border. The Daya river flows from Kuakhai near Bhubaneswar towards Chilika lake and forms the eastern boundary.

These rivers are part of Mahanadi river system, one of India’s major rivers which passes through the state’s old capital city Cuttack, 30 km from Bhubaneswar. From Mahanadi comes the Kathajodi branch which between them made Cuttack an island town. The Kuakhai river branches out from the Kathajodi river flowing southward towards Bhubaneswar.

Whither sewerage infra for a smart city?

Only some parts of Bhubaneswar have sewerage infrastructure; it is usually seen only in colonies developed by the local administration as government quarters or sold to private developers. But it has no proper disposal or treatment system.

The city’s sewage water flows through natural drains into the Gangua rivulet on the city’s outskirts which dumps this waste into the Daya river 10 km away. Presently, the Daya river is forced to carry the entire waste load generated in the city, which was originally planned for a population of 50,000 but today is home to 11-12 lakh people.

The two ruling BJD MLAs Pradip Maharathy (representing Pipli constituency) and Umakanta Samantray have been pleading with the Chief Minister to save the villages living in both sides of Daya from the pollution caused by Bhubaneswar city which has just one acqua treatment facility built in the 90s near Utkal university located within the city. And even that is not functioning well, said an official. After intervention by the National Green Tribunal, a small treatment plant has now been built in the Kalinganagar area of the city.

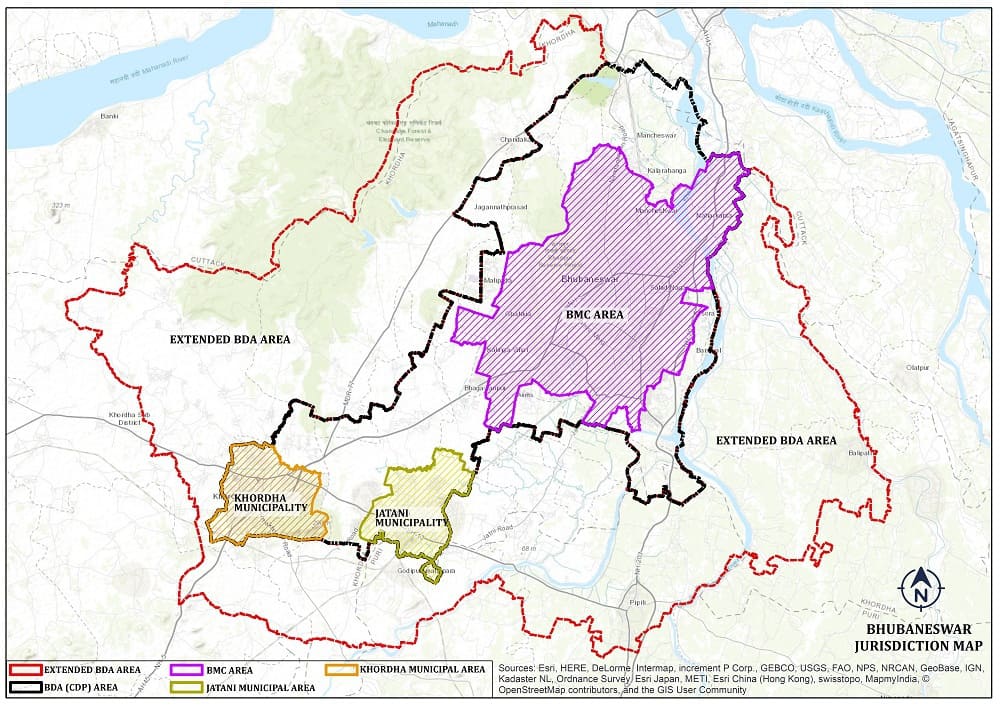

Map courtesy: BhubaneswarOne

Big plans

Bhubaneswar is only now getting started in building a bigger sewerage system which will cover more than half the city. A treatment plant is under construction in Basuaghai area which will prevent discharge of untreated sewage into the Daya river through the Gangua rivulet, said a senior official of WATCO, a newly formed state government body to handle Bhubaneswar’s sewerage system.

Unfortunately, COVID has further delayed the work on this which was in any case moving at a snail’s pace. “Bhubaneswar will have 100 percent sewerage treatment facility with the proposed six treatment plants with modern technologies,” said P.K. Swain and senior engineer with WATCO.

Swain explains the ongoing Basuaghai project will be the biggest of them all, and will be partially operational in early 2021. Three other treatment plants at Meherpalli, Paikarapur and one near Sundarpada are also under construction, with a total budget of Rs. 800 crores.

“By 2021, when these four treatment plants become partially operational, half the city’s sewerage will be treated,” says Swain. Two more plants at Pathargadia and Chandrasekharpur have also been proposed.

The state government is also planning a mega piped water supply project for villagers in Samantray’s constituency SatyaBadi. Samantray said the existing drinking water supply to some villages has been stopped since last year because of pollution.

“Because of sewage discharge, methane content in river water increases,” said Padmashree awardee environmentalist Prof Radhamohan. “Methane is more dangerous than carbon dioxide as it raises atmospheric temperature and quickens global warming. This interrelationship, added to the dumping of industrial waste in the river, can have a negative impact on climate.”