A recent gazette draft published by the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change proposed an ecosensitive zone for villages listed around Bannerghatta National Park in Bengaluru. “The State Government shall, for the purpose of effective management of the Eco-Sensitive Zone, prepare a Zonal Master Plan within a period of two years from the date of publication of Final Notification in the Official Gazette, in consultation with local people and adhering to the stipulations given in this Notification for approval of Competent Authority in the State Government,” said the notification, asking the State to prepare a master plan for eco-sensitive zone, in consultation with concerned departments in next two years.

Why does this matter to a Bengalurean?

For someone who lives in Bengaluru, it is hard to imagine a vast tropical deciduous forest just about 30 minutes away from the city. Dense tree canopies, untouched watersheds and plethora of wildlife in Bannerghatta National Park (BNP) that hold these forests stand in contrast to its host city- Bengaluru which is today a congested and polluted living space.

This 260 km2 large protected forest is unique: no other big Indian city has such an enormous forest region which is rich in biodiversity, so close to its urban limits. In fact, Bengaluru is likely one of the few metropolitan cities in the world, alongside Cape Town, Mumbai, Toronto, Nairobi and Rio de Janeiro, to host an urban forest-park.

Depleting forest causes stress among animals

But forests in BNP are facing an acute danger according to a 2016 study by Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru. Uncontrolled urbanisation, land encroachment, stone quarrying and mining are causing havoc to the ecosystem, eventually leading to substantial forest losses inside and outside the national park, the study warns.

Today, Bannerghatta National Park face challenges at multiple fronts: stunted tree growth, local extinction of many tree varieties, blocked pathways used by elephants and other wild animals, conversion of forest land for agriculture and pollution due to mining and quarrying.

Scientists from National Institute of Advanced Studies (NIAS), Bengaluru reported that elephants spent comparatively lesser time feeding or resting in areas in BNP that are disturbed by humans. In these areas, elephants showed what scientists call ‘bunching behavior’ which is a sign of stress in the animals. Similarly, another research found drastic increase in non-native species like Acacia and Eucalyptus plantations in the surrounding region of BNP within two decades.

A mosaic of wilderness makes way for quarries

Urban forests are natural heritage of a city. They are often a mosaic of wilderness, agriculture and cultural landscapes, featured with attributes that are fundamental to healthy, lively communities- green spaces, fresh water, organic food, nature-bound lifestyle and peaceful environment.

Bannerghatta National Park is replete with such sites. The breathtaking rocky hills from where Bilikal Betta (1075 meters) and Dodda Ragihalli Betta (1035 meters) rise to form a watershed of over a dozen streams- together form a conducive habitat for 130 species of birds and at least 32 species of mammals, besides enriching extensive fields of rice, ragi and fruits along with forest trails that crisscross with rural and peri-urban panoramas.

Yet for three decades, the Park’s fringe has been given away to destructive commercial purposes. Many tracts were auctioned to extract granite and other stones used in construction. A landfill site was built. Farmhouses and resorts encroached into the forest. Agrarian landscape turned to plantations, while plantations turned to housing layouts. Surprisingly, even Forest Department- the torchbearer of conservation- took a chunk off the forest and built a zoo safari!

Protected, yet in danger

To be sure, Bannerghatta National Park has been relatively secured off late. The 2011 move to merge a number of connected forest patches to the national park more than doubled the area under highest protection. Better use of GIS technology helped to digitize the park boundaries. The city planners have classified BNP region as a crucial green belt zone in Bengaluru’s Master Plan.

Today, the Park is off-limit for developers and infrastructure projects. Nevertheless, they are still pushing these projects- mainly real estate, stone quarries and roads- to the forest fringe, as close as legally allowed.

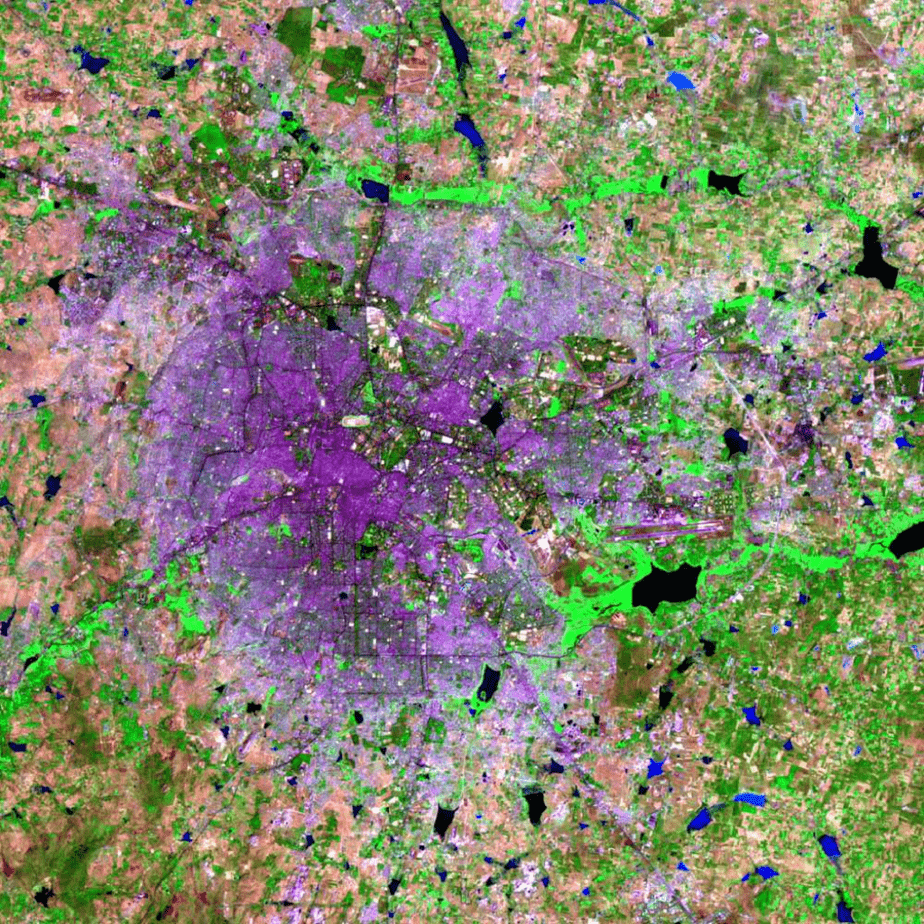

Landsat imagery of Bengaluru, showing that most areas are built-up today while a few green spaces are left.

Eco-sensitive zone leaves out sensitive areas

To prevent similar unscrupulous development, an eco-sensitive zone (ESZ) was proposed in 2016 around BNP, following orders from Supreme Court of India. This zone has only one purpose- to act as a shield against activities that harms the wildlife and biodiversity inside the national park.

But the proposed eco-sensitive zone ignored the suggestions from scientists at Indian Institute of Science. Out of 147 highly eco-sensitive settlements identified by their study, only 74 made into the proposal. And the situation started to appear dodgy, once even this pared proposal lay frozen until it lapsed last year without being notified.

Situation was now alarming. Public voices rose. Online petitions were signed. Media reported widely about the unreasonable delay. Finally, a revised plan of ESZ came out in November, last month. Except now, the eco-sensitive area was further trimmed by 37%.

On top of this extremely thin buffer, 16 settlements at the fringe of BNP have just 100-meters in the zone, while rest of them are covered up to a kilometer. Leaving one baffled, ESZ document explains nothing about why certain fringe areas are so small-sized and why buffer zones are fragile in parts.

The city needs to act at this moment. There is a chance with citizens to object the dodgy ESZ: they can send email to the ESZ executive committee under central government in New Delhi before end of December.

Although Bannerghatta National Park is managed by Forest Department, they are dependent on dozens of other public agencies to manage ESZ- an area outside the park. At the same time, forest officers face enormous pressure from politicians who hold lands close to the park. Hence, visible and firm public support to conserve BNP not only adds firepower to a solid ESZ, but also irks the detractors who have stakes in the eco-sensitive area.

Sandwiched between two growing cities

Rouge Urban National Park near Toronto, Canada runs a successful model of managing an urban forest by getting citizens on board. No such example exists in developing countries. If Bengaluru is able to preserve ecological balance of BNP through laws, supportive urban policies and effective eco-sensitive area, it might be a specimen for many other cities in the world.

The latest United Nations report on urbanisation pegs Hosur and Bengaluru in the top ten fastest growing cities in India. These cities are going to expand a lot in coming years, housing more than 12 million people and demanding a lot of natural resources for its roads, drinking water, energy, houses and recreation.

Between these two sprawling cities, lies Bannerghatta National Park. Just as there is no city like Bengaluru that hosts such a biodiverse urban forest, there is no urban forest like BNP that faces such a gigantic urban outburst. It is a unique place; it deserves to thrive.

Concerned citizens can send their objections/suggestions on Bannerghatta eco-sensitive zone to ESZ committee formed by Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change before 31 December 2018 via email to esz-mef@nic.in and moef-esz@nic.in.

For inputs, please see this author’s objections here.

esz-mef@nic.in is the email id given in the gazette. sending to moef-esz@nic.in as given in the article gives a failure notice.