Shanti Nagar is a popular shopping destination in Mira Road, a suburb just north of Mumbai. Shops and hawkers line both sides of the narrow lane, selling all manner of goods including clothes, shoes, utensils, bedsheets, jewellery, etc. Inevitably, a crowd gathers in the area every evening. But on Mondays, this equation shifts.

Mondays are for the ‘Monday market’. Since most of the shops are closed for their weekly day off, a wave of Monday-only hawkers descend on the street in the evening. They spread their goods on the porches of shuttered shops and in front of footpaths. Their biggest draw are the prices: Rs 100 for a winter jacket, Rs 50 for a t-shirt.

Haseena Khan, one such hawker, comes to sell accessories on Shanti Nagar from Malwani in Malad, an area known for its slums. After the death of her husband and sons, she started selling selling her wares on the street to support her two grandchildren, on the advice of her brother-in-law’s daughter. “If I get money from the business, then the household expenses for the week are covered,” she says.

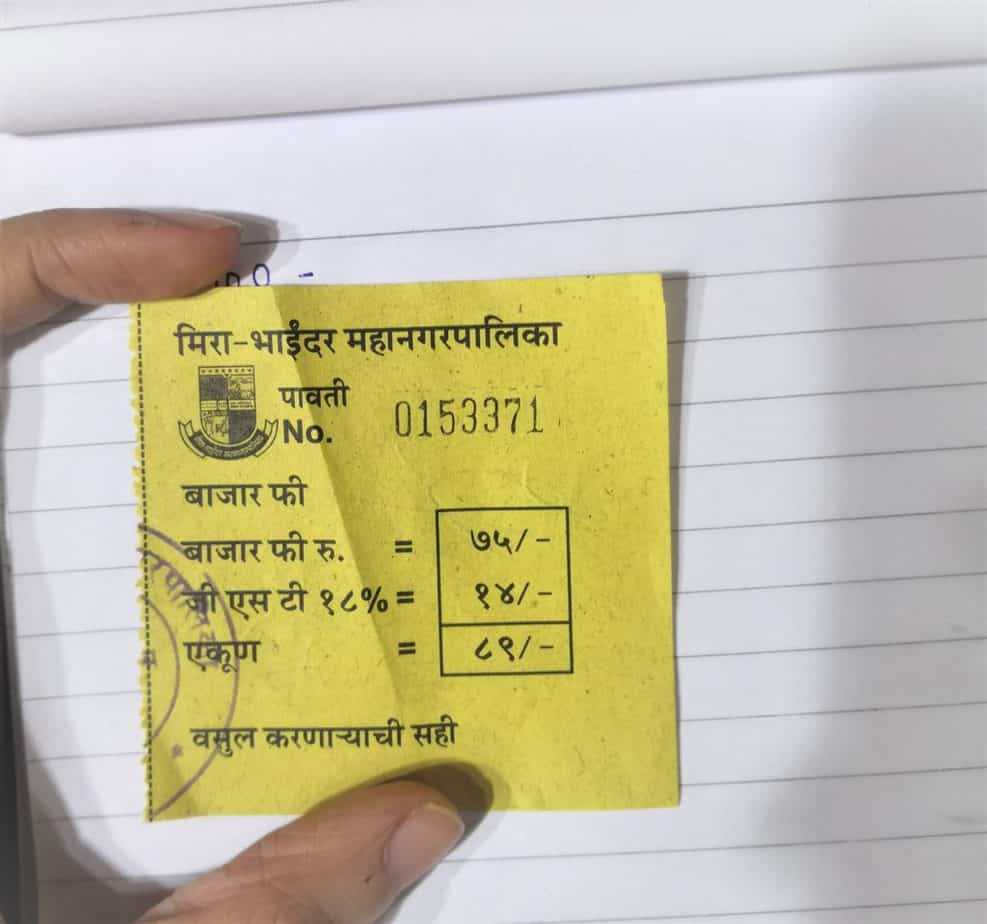

But Haseena has to pay for her place among the sellers. She displays a receipt issued by the Mira Bhayandar Municipal Corporation (MBMC), called “pauti”, that shows payment of a fee of Rs 89.

Varsha, a hawker sitting beside Haseena, selling occasion wear, corroborates this. She adds that the fee goes up to Rs 200 at Naya Nagar in Mira Road and near Santacruz station, where she goes on Saturdays and Thursdays respectively. A third hawker with a semi-permanent shop, who did not want to be named, alleged that he had to pay Rs 120 per week to sell clothes on Linking Road in Bandra.

Despite daily fees, hawkers still evicted

Unlike Hill Road and Linking Road, the Monday market on Shanti Nagar primarily caters to the local population. But, according to Chandrakant Borse, assistant municipal commissioner of the MBMC, the market is entirely illegal. “If we catch them, we take their goods and store them in a godown. If there are vegetable vendors, we tear their vegetable bags,” he says, pointing to a pile of bundles in a corner of his office.

The MBMC has made little progress in implementing the Street Vendors Act, 2014. It hired a private agency to conduct the first survey of hawkers in the area in August 2021, and found 7,221 of them. But no sooner than the survey was completed, it was revealed that it was full of errors. Other professions – from salespersons to security guards – were included among the hawkers. A verification process of the list is now underway.

Separately, the municipality had identified 26 hawking zones and 66 no-hawking zones in 2017. While this is the responsibility of the constructed Town Vending Committee (TVC), with representatives from the municipality, police, hawkers, residents and NGOs, multi-crore contracts were awarded to collect daily fees from hawkers in hawking zones.

This, however, has backfired for both the municipality and hawkers. “The contractor dismisses the rules and regulations and takes the daily fee from everywhere, regardless of hawking zone,” says Jaishankar Singh, a member of the Azad Hawkers’ Union. “So the pauti holds no meaning. They still come to inspect and clear the hawkers.”

A system of bribe benefits the civic body

The Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) started to use a pauti system in 1988, in lieu of licences. The fee, which started at Rs 5 – Rs 15 and went upto Rs 30 – Rs 100, was called “unauthorised occupation cum refuse removal charges.” The hawkers’ illegal, or “unauthorised,” status did not change under this system, but the recognition gave them some legitimacy to the space they occupied. The system was also lucrative for the corporation, reportedly earning them up to Rs 146 crores every year.

Simultaneously, the BMC was working on a scheme for a hawker policy, in accordance with the guidelines of the 1985 Supreme Court ruling to demarcate hawking and non-hawking zones and provide licences for the former. A collective of corporation officials, traffic police, NGOs, and representatives from among hawkers and resident welfare associations (RWA) drew up a draft scheme in 1996, marking 488 hawking zones which would accommodate 49,000 hawkers. The rest would get spaces in hawker plazas, separate contained spaces for hawking.

At the time in 1997, a survey by the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) and the non-profit YUVA, in collaboration with the BMC, found that there were over 1,03,000 hawkers in Mumbai. 15,000 had old licences issued before 1950, while 22,000 were issued pautis.

It was the pautis, however, that got the BMC back in the Bombay High Court in 1998. The Citizens’ Forum for the Protection of Public Spaces (CFPPS, which later became Citiscape, and now is Nagar) filed a petition claiming that instead of regulating them, hawking was flourishing under the pauti system. The BMC had admitted to earning over Rs 2 crore from pautis between August 1998 till April 1999. But with no legal backing, they had to stop.

Read more: On BMC’s ‘eligible’ list, why are hawkers in Mumbai still evicted?

The pauti system takes a new form

The official end to pautis, apart from their continuation in pockets like Mira Road, did not mean the end of monetary exchanges between officials and hawkers. It merely took on a different shape: the hafta.

A loosely negotiated bribe, also referred to as protection money, the amount of hafta taken differs from area to area, depending on the nature and quantity of the product being sold. Cooked food has a higher profit margin and costs a higher hafta than fresh produce, writes Jonathan Shapiro Anjaria in his book on street food in Mumbai, The Slow Boil. Those in expensive neighbourhoods and popular shopping destinations have to pay more than those in poorer neighbourhoods. The hawkers in the subway outside Churchgate station, for instance, were caught paying Rs 50 in a video taken by Vivekanand Gupta, the secretary of Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) Mumbai in 2019.

The non-uniform nature of the bribes makes it hard to put a number to it. A conservative estimate of Rs 50 given by each of the 3 lakh hawkers in the city adds up to Rs 550 crore annually. Mecanzy Dabre, deputy secretary of the National Hawkers Federation (NHF), estimates the amount at Rs 800 crore every year.

“Every hawker informally shells out a lot of money to ensure that their vending continues, and the system benefits from the corruption,” says Aravind Unni, an urban planner formerly at YUVA. “If the Street Vendors Act were to be implemented, it would transfer a lot of revenue to the BMC. But the status quo is currently maintained by the informal relationships between the lower rungs of the bureaucracy, administration and the street vendors on the ground who willingly pay hafta.”

A parallel ecosystem

The undefined nature of the hafta has meant the implication of a lot more players than just officials. It now extends to middlemen, shopkeepers who the hawkers are parked in front of, politicians, goons, and other hawkers too. A parallel system thrives, of informal land claim, where hawking spots are rented and sold. Sometimes ownership is claimed based on long-standing presence, while others operate under the stronghold of a powerful few, often dubbed the “hawker mafia.”

In the latest such revelation, a hawker was caught in August 2021 for collecting hafta from hawkers at the railway stations between CSMT and Kalyan for years. He had employed other petty criminals for the collection of Rs 500-5000 a day, continuing the practice even when he was behind bars (this is despite the fact that areas 150m from railway stations are clearly marked as no-hawking zones). The BMC’s own central encroachment team, called ‘Bombay Special’, was disbanded in 2017 for taking bribes off hawkers on Fashion street in South Mumbai.

“The hawkers have gotten used to it. They fear that if they don’t pay the hafta, their goods will be taken away,” says Dayashankar Singh, president of the Azad Hawkers’ Union. In exchange, the hawkers get a tip off before the municipal “gaadi” makes its way to the scene, maintaining the illusion of a functioning state. “It’s all for show,” says Dayashankar.

The hafta, however, is not a complete guarantee. “The security that hafta gives the hawkers is very conditional,” says Mecanzy. “Evictions can occur when people complain, or there is a block in traffic, if a senior officer demands it, or to show the maintenance of order. The officer taking the bribe cannot protect the hawker based on the bribe.”

In the cases when the hawkers’ goods are confiscated, an additional bribe is paid to get them back. Other times, says Aravind, eviction drives are a smokescreen for a re-negotiation in hafta.

Implementation

The Street Vendors Act, 2014, was meant to formalise hawking, but this is yet to be achieved. Maharashtra in particular has had a dismal record, according to the research organisation, Centre for Civil Society (CCS).

While the state had a compliance score of 49 in 2017, it was reduced to 28 in 2020. No town had constituted a regular Town Vending Committee (TVC) with elected hawkers, and none of the identified eligible workers (only 75,000 were found) had been issued a hawker identity card or vending certificate. As a result, informality continues to reign.

There might still be room for a change, indicates Aravind, considering the strides other cities have made in implementation. Jharkhand, in particular, has a compliance score of 60 and framed a scheme on the Act within two years of it’s passing. It is also one of the few states that have elected the hawkers representatives in the TVCs, and have issued vending certificates and identity cards to some of its hawkers. “Mumbai requires some hand-holding and guidance, as well as support from the State. The government isn’t doing much at this stage, but our belief is that it is possible,” says Aravind.