In the many years that I have lived in Mumbai, I have perfected a method of walking from the Western Express Highway metro station in Andheri East to my apartment, a kilometre away.

First, I sprint to cross the road. Then I use the momentum to jump onto a footpath. A little ahead, 90% of the footpath is encroached by a shop. So I turn to my right, extend my arms, and maintain balance as if the footpath were a surfing board. Then I leap over a variety of automobile parts displayed by the shopkeepers in the shopfront.

Like me, 1.5 crore people sprint-jump-surf-leap on footpaths every day in Mumbai. Despite the hurdles, walking is the most preferred means of transportation, with about 25.74% of the working population walking to work. Others walk to auto rickshaws, buses, taxis, and trains.

But Mumbai is tough on its pedestrians. It was ranked 27th among 30 Indian cities evaluated on their ‘walkability’ by the Clean Air Initiative, an organisation involved in assessing ease of walking in Asian cities.

Walkability means foot friendliness where every walking trip doesn’t become an obstacle race. It’s about levelled footpaths, proper lighting, and safe intersections. Trees along footpaths are a great add-on but best expected in a few opulent parts of the city.

The government imagines a Mumbai road primarily in terms of vehicular traffic. Hawkers are dismissed as encroachers and pedestrians, while large in numbers, are not mobilised, and therefore invisible. “What’s not taken into account is that people also walk, cross, rest, run businesses, and celebrate festivals on the street,” Dhawal Ashar, Manager, Urban Transport And Road Safety, World Resources Institute (WRI) India Sustainable Cities, says.

One Brihanmumbai Corporation circular, too, asked for footpaths to be “connected” and “continuous”, to be “wide enough to accommodate pedestrians” at all times, and “to be firm and even-paved” so that even wheelchairs could pass on it. Till 2019, BMC had spent Rs 150 Crores on footpath repairs, but slip-resistant, bumps-free footpaths, or pothole-free roads as an extension, remain a pipe dream.

Streets as public spaces

Mumbai is not renowned for parks, open grounds or even green patches, hosting a paltry 1.1 sq km of public space per person as opposed to 30 sq km in Delhi.

Streets, then, are the only continuous network of public space in the city. On such a street, a footpath, if it exists, “is often 1.6m wide, sometimes only on one end,” Ashar says. Add to this the utilities obstructing a footpath like a bus stop, an electric pole, railings and “you have an unusable pavement in the days of physical distancing,” Ashar adds.

BMC which looks after maintenance of infrastructure in the city re-lays footpaths and roads repeatedly, but they crumble soon after.

Tired of broken roads and footpaths in her Chunabhatti neighbourhood, Vridhi Jain, 24, took it upon herself to find a solution. Last year, she approached the corporator, met with BMC officials, and spoke to road engineers. “I would be sent from department to department,” she recalls, of the three months spent in understanding why her neighbourhood couldn’t have decent public infrastructure. “There was an endless blame-game from BMC to Public Works Department (PWD) to MMRDA to the road contractor with no resolution in sight,” she says.

It’s a complaint heard ad nauseam. In one particular street, the jurisdiction stretches from BMC to state and parastatal bodies such as MMRDA or state government departments like PWD along with transport wings like BEST and Railways. “They all have to be brought together if any work has to be done,” Ashar says.

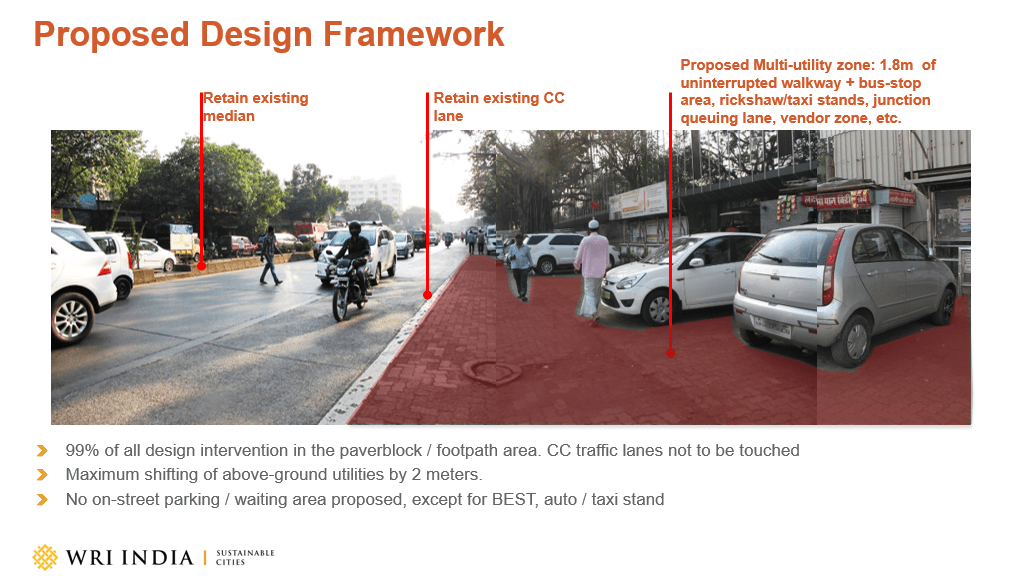

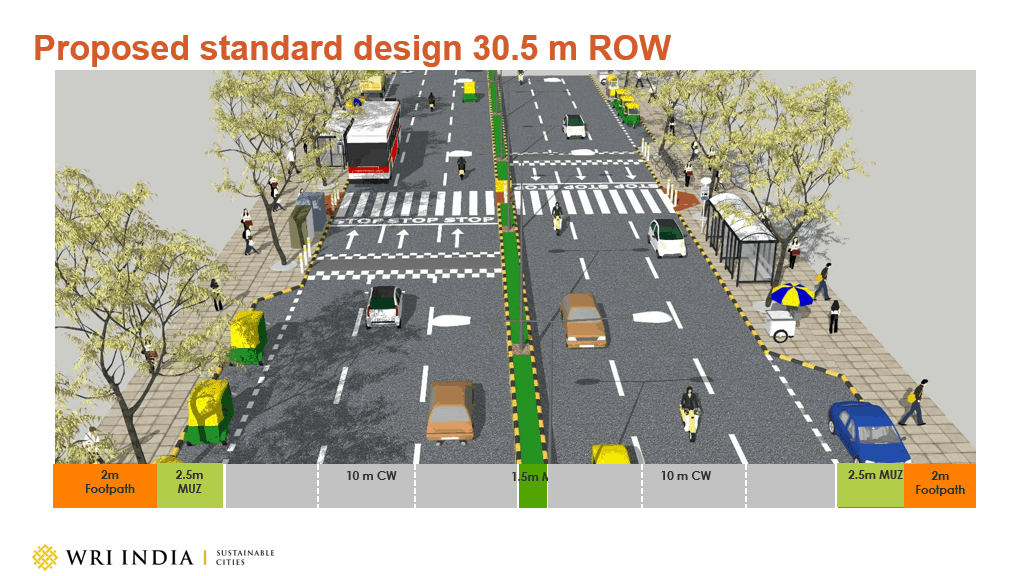

It’s precisely what he, and his colleagues at WRI, did at LBS Marg for a project in collaboration with BMC and Bloomberg Philanthropies Initiative for Global Road Safety. “We managed to convince them that the vehicle carriageway should remain the same whereas the footpath width needs to increase,” Ashar says. As a result, they built a 4 meter footpath (2 meters on both sides of the carriageway), but they still couldn’t achieve a continuous stretch as it is obstructed by car parking.

While disjointed and irregular, these initiatives point at a need to free street management from the clutches of a contractor and infuse new talent in bureaucratic functioning.

In 2019, BMC initiated a programme called the Mumbai Street Lab (MSL) in partnership with WRI. It invited architects and urban designers to facilitate the transformation of five streets in Mumbai: SV Road, Napean Sea Road, Vikhroli Park Site Road no.17, Maulana Shaukat Ali Road and Rajaram Mohan Roy Road. The proposals were subjected to procedural review and five were shortlisted by a jury comprising of government officials and experts.

Instead of generic solutions that could be copy-pasted to different parts of the city, this initiative brought in “specificity”, according to Rupali Gupte, Architect, Urbanist and a jury member of MSL. By choosing five streets, the winners could conceptualise interventions according to what that street needs.

Bandra Collective Research and Design Foundation won the competition to reimagine the Vikhroli site. It proposed to expand the street median to increase pedestrian activity along with adding segments at intervals of 100 meters. Its proposal also includes a cycling track with provisions for temporary markets and stalls, urban furniture and social public spaces. The project claims to add approximately three acres of green public space to the neighbourhood. “The project is at an advanced stage,” Zameer Barsai of Bandra Collective says. “We are preparing working drawings and have submitted costings to the BMC.”

Executing plans better

Transport planners have long complained about a lack of planning and design in urban spaces. “Tourism-based economies that value aesthetics tend to take design far more seriously” Gupte says. But design which is simply “organising space” in a manner that is functional and efficient, should be emphasised.

Many big ideas float in Mumbai but rarely see completion. Transport planners talk excitedly about multi-modal integration such as, if you exit a railway station and can immediately board a bus to your destination. But in Mumbai’s Mahalaxmi station, for instance, Ashar points at how a passenger can’t even cross the road easily to reach the bus stop in time.

Right across the Vashi creek, the city of Navi Mumbai which was planned under City and Industrial Development Corporation (CIDCO), has far better infrastructure. But CIDCO, too, tried to create an automobile-friendly city with wider roads and junctions but till today, users of public transport in Navi Mumbai face several difficulties.

Mumbai, with the exception of the island district built by the British, sees a patchwork of public infrastructure at best. “From the 90s, the government withdrew from infrastructure as a provider and became a facilitator,” Gupte says. “For a long time architects were only doing private projects”, and only now there’s a resurgence, she adds, indicating initiatives like MSL and some other projects that new architecture and design firms are taking up with BMC.

“Urban design is civil engineering as much as it’s social science,” Ashar says, “and over time urban designers should become a part of the system.”

Designing streets for pedestrians

Historically, large infrastructure projects like the Coastal Road or Bandra-Worli Sea Link have governed state imagination. But these projects only aide automobiles, not pedestrians. A February 2019 study by MMRDA showed that there is a 150% rise in private vehicle ownership in Mumbai in two years.

“For the last 20 years, we’ve built flyovers, highways, freeways and mega-budget projects that bring more vehicles out on the road that cause traffic jams,” Ashar says.

Let’s widen the idea of “road widening”. When governments plan road-widening projects, they only think about widening the carriageway or where the vehicles ply which increases the number of vehicles on the road. Widening the footpath, in fact, can fix a lot of problems with the street. It can offer some shopfront to shopkeepers, some space for vendors, and of course, space for pedestrians to walk. “Design for pedestrians,” Ashar says, “and you will improve efficiency for all”.