Should we allow more apartments to come up near Kanakapura Road in Bengaluru because it has a metro line that can help people living there to commute? Do we allow more tech parks near Guindy in Chennai because it is well connected by bus and suburban train? Did Mumbai grow around the local train? Are transit lines the new age rivers?Transit oriented development (ToD) or development oriented transit (DoT) — What should it be for Indian cities?

Are these some of the questions that play on your mind when you think of what is happening in our cities today in the name of ToD?

This column tries to understand what the core essense of a ToD/DoT is; whether they are two different sides of the same coin to be used differently in different scenarios or if one is better than the other, and how cities, globally, have planned ToDs/DoTs and benefited from it.

What happens in Transit-oriented Development (ToD)?

Transit Oriented Development is a type of community development, where there are vibrant, walkable and bikeable mixed-use neighbourhoods; neighbourhoods that have a good mix of housing, office, retail shops and/or other amenities located within a kilometre of quality public transportation.

ToD is a sustainable practice. Research by Portland Metro has shown that the residents of neighbourhoods with good transit access and mixed-use development use their cars 29 percent less than in suburban neighbourhoods. This is primarily because ToD makes public transport accessible, inducing a reduction in traffic and congestion.

This means lesser air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. Neighbourhoods are safer because there are more people on the street and more “eyes on the street.”

It encourages mixed-use which means every public transport hub has a rich mix of housing, jobs, shopping, and recreational choices. Research at Cal Poly Pomona has shown that people who live in areas with ToD are five times as likely to use public transit as a resident of the area at large, and people who work around a ToD are 3.5 times more likely to use the same.

ToD improves the “location efficiency” which means more people can walk, cycle and take the public transport. The more compact and mixed the neighbourhoods, the better it is for developing a sense of community, including efficient use of land, energy and resources which can be used to increase open spaces.

For a city, transit-oriented development helps in increasing property values, lease revenues and rents. For retail, it increases foot traffic for local businesses. It creates an opportunity to build mixed-income housing.

Is it the right choice in any situation?

Transit-oriented development can be done in two scenarios. One, when it’s a greenfield development where the development of the town as projected for the next 15-20 years aims at greater dependence on public transit than private transport, and strives to get there right from the start.

In cases of built in cities, where transit modes such as metro rail are being fit into an already existing urban fabric, one tries to maximise and optimize the development around the transit to help people live and work around this transit and hence decrease private car ownership as well as increase ridership of the transit.

In either case, the city has to be committed to the actual goals of creating ToD — that is, creating sustainable communities which are mixed-use, walkable and bikeable around a transit.

These goals need to be strengthened by ensuring a good mix of uses and housing (especially affordable housing) at every transit node as well as by defining parking maximums. Without strengthening measures which discourage private car ownership and encourage people of all income levels to live around transit, the impact of this kind of development will not be seen.

There are opponents to ToD as well. Some say the urban built form and zoning should drive transit and not the other way round, which they call development-oriented transit (DoT). This is especially true for already built in cities such as Bangalore.

What makes ToD effective?

Transit such as metro which has the flexibility to go underground should be planned to maximise connectivity between places which couldn’t be connected by suburban train, and the bus should feed into the metro making the whole system more efficient.

Hence, a very important seed in the success of a TOD is, as the developers say, location, location and location. It is extremely important to locate the transit nodes at places which need minimum intervention to bring people into the station.

A bus-based mobility system is flexible to land use changes and demographics. It’s difficult to do this for a mobility infrastructure based on the train. In heavily populated areas where the train is required, it’s best to maximise that benefit by incentivising development around the stations and allow the bus to complement it. So a ToD around rail and a DoT from there on a bus-based backbone might be a hybrid that can get the best of both worlds.

The rediscovery of transit as a catalyst for development and redevelopment in the present is more than anything else, a response to the ravages of automobile-based sprawl in the latter half of the 20th century. Many cities in the United States and South America which are predominantly automobile dependent countries tried to use this concept of ToD to bring back better development at the centre of their cities which were abandoned due to suburbanization and sprawl.

Scales of Transit Oriented Development

ToD can be realized at various scales depending on a city’s strategy. The various examples below will showcase the idea of a ToD at varying scales.

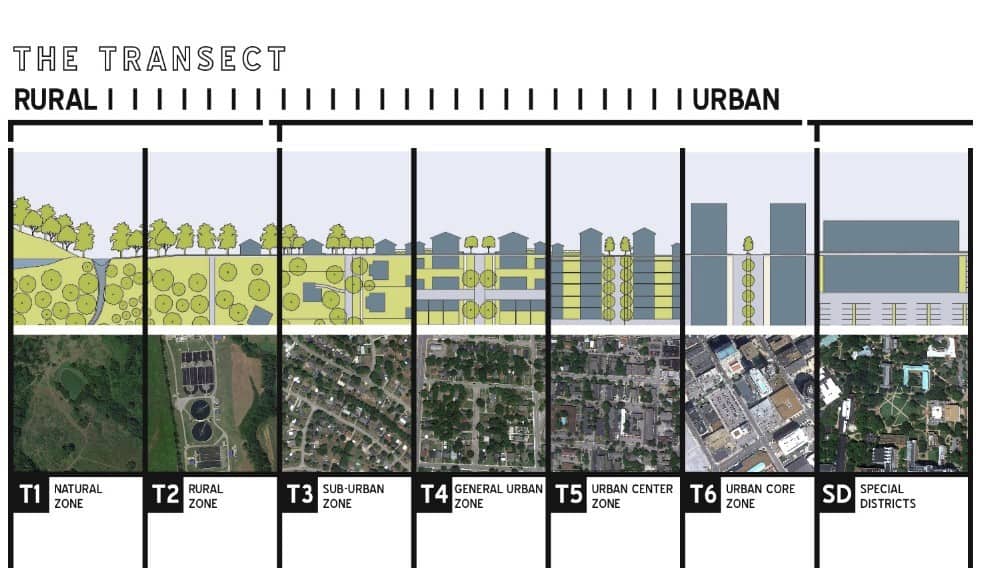

Every city or a node has a Transect, as defined in an urban planning model created by New Urbanist Andrés Duany. The Transect defines a series of zones that transition from sparse rural farmhouses to the dense urban core. In the Indian scenario, this would translate to villages/sparse developed areas at the peripheries of cities.

Each zone is fractal in that it contains a similar transition from the edge to the center of the neighbourhood. The ToD needs to be planned based on the transect in which the transit station lies. The treatment and design of the ToDs depend much upon the type of transit station and the scale of the development.

Duany’s “Urban to Rural Transect” (1999) identified a series of conditions from the urban core to wild nature, and proposed that planning policies change as densities varied.

Let us look at a few examples.

Shibuya, Tokyo, Japan: Regional/City level

Shibuya is one of the sub-centres in Tokyo and is on the circular Yamanote Line. It is an area where various activities like commerce, office etc. are agglomerated with high density around the railway terminal. Five railway lines carry 2.4 million commuters through Shibuya Station. The entire centre has an underground system of transit, well connected to the city that thrives above it. Train stations have become public spaces today in Japan and have attracted retail and other uses which make them vibrant.

Curitiba, Brazil: Corridor level

The brilliance of ToD is that there can be incremental changes in the choice of mass transit like Curitiba, Brazil has done. It built the transit lines along the major corridors in the city and developed them as spines in the city with a Bus Rapid Transit System (BRTS), due to funding restraint. As the TOD was realized and more people living around the BRTS have started taking public transport, the government is now planning to replace the BRTS with a rail network.

Portland, Oregon, USA: District level

Portland is one of the country’s highest ranked city in terms of its sustainable development practices and techniques in urban planning. The city is heavily built around rail transit and has around 85 km of light rail, 24 km of commuter rail, and 6 km of the streetcar system. The city has planned TOD across the entire transit network covering all the above transit lines.

A post on the blog Ideas for Vibrant Cities says TriMet, which is Portland region’s transit agency, has declared that more than $10 billion in development has taken place near the Max light rail stations and the streetcar has provided an even larger return on investment since it was implemented.

It also tells us:

“According to a report from the City of Portland and Portland Streetcar, Inc., $3.5 billion in real estate investments were made within 2 blocks of the streetcar alignment in less than 7 years (from July 2001 to April 2008). Since the total capital cost of the streetcar line was only $103 million, the benefits of the Portland Streetcar streetcar line far outweigh the costs.

Of course, the Portland Streetcar wasn’t the only factor that led to the city’s massive urban revitalization. Rezoning, tax increment financing for public improvements, and other public policies played an important role. However, the streetcar was undoubtedly a primary enabling factor for much of Portland’s urban renaissance over the last couple decades. The streetcar’s positive effects on real estate development are most easily seen in the Pearl District, a former declining industrial district just north of downtown Portland that is now a vibrant urban neighborhood. Portland’s Pearl District is widely regarded as a national best practice model for urban revitalization.”

Del Mar Station Transit Village, Pasadena, California : Block level

Del Mar Station is a 3.4-acre Transit-Oriented Development located at the southern edge of downtown Pasadena, around the Metro Gold Line connecting cities of Los Angeles and Pasadena. This development serves as a gateway to the city of Pasadena. The development consists of 347 apartments, out of which 10,000 sq.ft. are affordable units.

Approximately 20,000 square feet of retail is linked with a network of public plazas, paseos and private courtyards making it a buzzing place around the transit. This development was not conforming to many of the existing zoning regulations of the city, but the architects and the developers took the onus of applying for eight different variances to get this project approved including height, setbacks, and parking.

Parking was sought to be reduced to 0.5 per unit to realize the effects of ToD, but the city at the time was not ready for this concept and hence only approved it to be reduced from 2 per unit to 1.8. However, the success of the TOD today can be applauded due to the fact that half these parking spaces are empty.

Designing it right

However, it’s important to do ToD right, getting it wrong may have unintended consequences. The vision of providing a mix of uses while developing the area around the transit and thinking of each transit node as a community around the station is a critical principle that cannot be forgotten when embarking on place-making.

Providing infrastructure and facilities around the public transit station which makes people walk or cycle to the station allows the ToD zone to be designed right. Ultimately the city should build a place not make a project.

The Transit Oriented Development Institute recently conducted a seminar around the various best practices and strategies on how to make TOD more meaningful in the cities across USA. Mr. Vinayak Bharne, Principal, Moule & Polyzoides talks about some very interesting fundamentals on the development of TOD which are applicable in any country that is looking to do it. The video for the same can be found in this link.