Ravindra Jhagde, 42, has a story to underscore how well-respected his father’s job as an operator in Standard Mill, Prabhadevi, used to be. “My cousin’s husband had to pick between two job offers. He could be a teacher in a government school in or around Bhor in Pune, or he could be a mill worker in Mumbai like my dad. He chose the latter.”

Jhagde is a vegetable and fruits wholesaler in Dadar, barely a stone’s throw from the slum home he grew up in, where his mum and sister operated a khanawal, a traditional Maharashtrian eatery, from where they served packed lunches to dozens of mill workers in Parel and Dadar. They were never well off, but Jhagde speaks of those years, before the de-industrialisation and gentrification of Dadar, Parel and Lalbaug in central Mumbai, with nostalgia and sadness — the shiny new skyline around their home, the new flyovers, high-rises and malls have been life-altering.

In its proposal to the Union government’s Smart Cities project in 2015-16, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) said nearly Rs 2 lakh crore had been invested in the Lower Parel region, the mill land, in recent years, and that the region generated a sizeable share of the city’s GDP. Structural changes in the economy after liberalisation in 1991, saw a rising demand for commercial and retail spaces, and the derelict former industrial district delivered. As land use in the mill district changed from industrial to residential and commercial, property prices rose seven-fold between 1991 and 2005.

That prosperity did not touch Jhagde, whose father returned to his native village in Velhe, Pune, after working for 24 years. Jhagde and his brothers, all educated, struggled to find livelihood in a rapidly changing cityscape. One brother, a skilled gardener, has been unemployed since the pandemic. Unable to buy a home in a market with skyrocketing prices, the family continues to wait for the long-promised subsidised housing for mill workers.

“Our locality changed before our eyes,” said Jhagde. “We would hear the sirens of the mills and know it was 3 pm, time for the workers to leave for the day. We could play in the open maidans all day. We went everywhere on foot. Now there is such terrible air pollution and the din of traffic all through the day.”

Former Mill Land: Premium Site for Urban Congestion

It was a combination of circumstance and policy that led to Lower Parel’s current status as a premier business hub and the unprecedented densification of ‘Girangaon’, the land of the loom, the contiguous areas of Dadar, Parel, Currey Road, Chinchpokli and Lower Parel.

A few years after the crushing 1982 textile workers’ strike, many of the 54 cotton textile mills in Mumbai slipped into insolvency. In 1991, Regulation 58 of the new Development Control (DC) regulations tried to use the expansive swathes of central Mumbai these units occupied – nearly 600 acres – to generate open spaces and public housing for the city while also allowing private mill owners to sell assets and recoup losses.

As per Regulation 58, one-third of the mill lands would be reserved for public purposes such as parks, maidans, schools and hospitals; another third for affordable housing, and a final third could be commercially developed with a higher FSI.

In 2001, on the urging of mill owners and lenders, the Maharashtra government modified Rule 58 — only land not occupied by any structure in the mills would be thus divided. It was a real estate bonanza for mill owners, one that was litigated and hotly protested by citizens’ groups, but one that prevailed. As a result, land to be ceded for open spaces reduced from 166 acres to 32 acres; and for housing from 160 acres to 25 acres, effectively ending the prospect of using the mill lands, originally leased to mill owners at low rates, for a city rejuvenation programme.

The textile mills had uniformly consumed an FSI of 0.5, sprawling but low-slung structures. The new buildings were granted FSI of 2 or 3, this real estate entering the market just when the supply of office space in Nariman Point had stagnated, leading to some record real estate deals when the mills were auctioned. Multiple incidents in later years would point to the absence of planning in Central Mumbai’s realty boom — a stampede at Elphinstone Road railway station claimed 22 lives, a fire in a Kamla Mills pub claimed 14 lives, daily traffic pile-ups continued despite the addition of flyovers.

Read more: Is the BDD chawl redevelopment Mumbai’s chance for course correction in urban planning?

A Metamorphosis Nears Completion

Architect and urban researcher Neera Adarkar said it was unfortunate that the fears she and others had two decades ago, that the development of the former industrial lands would fail to generate accessible open spaces and affordable housing, are now a reality. “The city lost an opportunity,” she said.

Not only did the amended plan offer only about an eighth of the mill lands’ area for creation of public amenities, she said, but also no survey was conducted to assess how much of this land was in fact ceded and the amenities built, or to verify if the new ‘open’ spaces were accessible to all. The municipality, which had to anyway sanction all plans for construction on the mill lands, should have enforced the surrendering of land meant for open spaces, according to Adarkar.

“The new constructions became gated communities and are now difficult to survey even visually,” Adarkar said. “Also, this is high density-low occupancy development, 30-storey or 60-storey buildings meant for only a very small class of people.”

The transformation was painful and impacted their lives in multiple ways, said Jhagde, who now lives on rent in Dadar’s Ambedkar Nagar. He reminisced about walking from Dadar to Crown Mills in Prabhadevi in pouring rain to deliver dabbas as a 12-year-old boy, the wide open maidans where he played as a boy, some of them now barricaded for infrastructure construction work; about the 24-hour water supply they enjoyed compared to the limited hours of supply now. “Now we cannot let children even cross a road without a chaperone — there is such heavy traffic.”

The mill precinct’s socio-economic fabric is now awash with bitterness and desperation. The Jhagdes are waiting for their turn in a long list of mill workers’ families hoping to get a state-constructed home as promised. The Girni Kamgar Sangharsh Samiti, the workers’ union that has continued to agitate for the rights of the mill workers and their families, said only 18,000 homes had been handed over through auctions, while over 1.7 lakh had signed up for the scheme.

The transformation of the built form of Girangaon is linked closely to livelihoods. The closing of the mills marked a decline of manufacturing, growth of the service industry, and a consequent pushing of skilled labour into informal labour, contract work, loss of social security schemes, insecurity of job tenure, etc. By the end of the Eighties, as the mills collapsed, the Mumbai underworld had found the unemployed youth of the mill district ideal recruits. Today, with unemployment high again, many mill workers’ children like the Jhagdes, now in their thirties and forties, are graduates working as vegetable vendors, or as delivery partners or gig workers for app-based services.

The former mill land’s redevelopment rode on high property prices, with planners ignoring other aspects of the value of the space. As a result, according to Adarkar, bureaucrats failed to imagine vibrant open spaces and world class amenities that are inclusive.

A Lost Opportunity For Participatory Planning

Marina Joseph, associate director at YUVA, a Mumbai-based non-profit that has done extensive advocacy and research on urban issues, said participatory urban planning for the mill district could have mitigated some of Central Mumbai’s current deficits in affordable housing, traffic and public transport planning, etc. “Whether it is the mill lands or the port authority’s lands on the eastern waterfront, a wider city-wide citizens’ movement saying this land belongs to the city has not emerged,” said Joseph. “The younger generation, which has never seen the mill lands beyond their fortified walls, has not seen these spaces as something they can access, almost as if that part of Mumbai doesn’t belong to them.”

The active campaigns by mill workers, architects, and citizens’ groups fighting for open spaces were still rarefied voices, said Joseph. “For truly participatory planning, there must be in public imagination a view that the people have a right to these lands.”

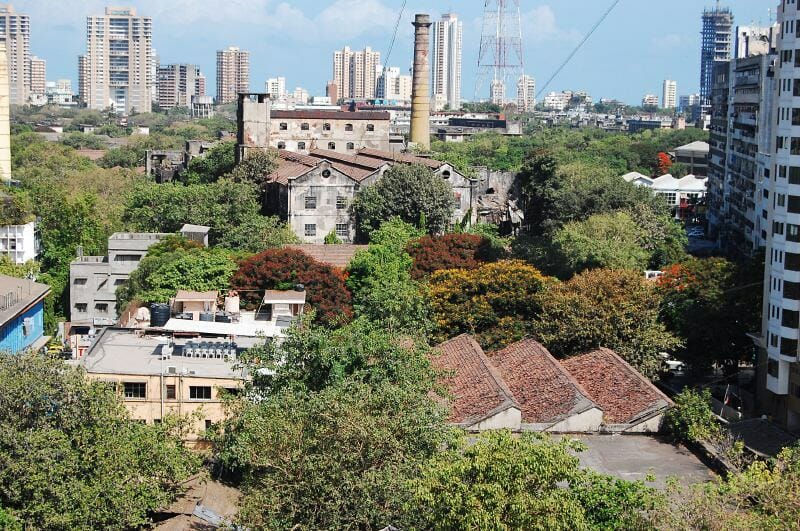

There were other losses for the city: structures of heritage value, including 15 feet stone walls, weaver’s sheds, many structures in 19th Century style, water bodies, the occasional chimney standing 30 feet tall, were carefully marked out by architects and students, but were never notified or protected. A city’s built form often reveals its histories, but most of these structures have now vanished, said Adarkar, who led one exercise to document heritage structures in state-owned mills for the Mumbai Metropolitan Region-Heritage Conservation Society.

Girangaon’s physical and socio-economic transformation is not over. In January 2023, the union minister for textiles, commerce and industry Piyush Goyal said 11 dilapidated chawl buildings on land owned by the National Textile Corporation (NTC) would be redeveloped soon, with 2,062 occupant families to be rehabilitated.

This will be a further recasting of the city’s built form, viewed by planners only as land and a real estate opportunity, unmindful of the lives and livelihoods tethered to the now defunct looms.

This article is part of a series of articles on Urban Planning in Mumbai, supported by a grant from the A.T.E. Chandra Foundation.