In 2017, 3Wayste– a French firm–submitted a proposal to the Government of Karnataka (GoK) and Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) to implement an integrated municipal solid waste (MSW) management project at Chikkanagamangala. Using the company’s proprietary, patented waste-to-energy technology, the plant would generate electricity from processing MSW, i.e refuse derived fuel (RDF), converting the existing MSW-processing plant to an incineration-based WTE plant.

The plant was intended to process 500 tonnes of mixed waste (300 tonnes supplied by the BBMP, and 200 tonnes from other sources). 3Wayste proposed to process refuse-derived fuel (RDF) to generate 9.2 MW of power.

After 3Wayste received the required departmental clearances, the GoK issued an order on March 8 2018, to put the plan in motion to convert their MSW plant into a WTE plant. However, the process was embroiled in conflict as residents in Electronic City (where the plant was located) protested against the “misguided attempts at scientific waste management.”

“Before the plant was set up, the government made a lot of promises that the plant would use technology that would prevent the stench from emanating, but none of them have materialised,” says Venkatesh Guru, a resident from Chikkanagamangala. While leachate has to be disposed of properly through rajakaluves or stormwater drains, residents say the plant has disposed of it at the Chikkanagamangala lake, which is located a kilometre away from the plant.

“The lake is completely polluted now. We keep protesting, but they find ways of using the local police to intimidate and shut us up,” says Venkatesh, adding that the residents do not believe the WTE plant will benefit them in any way.

The resistance from local communities remained, despite 3Wayste saying in its initial proposal that it would “implement a state-of-the-art odour and dust control system”, and ensure that the BBMP would transport waste in covered trucks. The plant would also require a license from the Pollution Control Board due to the smell it would emanate.

In November 2020, the state Urban Development Department withdrew the consent issued on the grounds that the company failed to deliver on its promises. “The company was asking for too many concessions. Also, over the last one-and-a-half years, the firm did not show interest in establishing the plant,” the report quoted Sarfaraz Khan, the then-Joint Commissioner of the Solid Waste Management division, BBMP.

Budgetary push and Western rationale

Domestic waste contains hydrocarbons that “can be converted into electricity using thermoelectric and anaerobic digestion plants” through a combustion process that produces pollutants as well as green gases, according to Science Direct in 2021. It argues that converting waste to watts, energy and value-added chemicals is “the way forward for long-term sustainability.”

The paper refers to the United States Energy Policy embracing WTE technology and endorsing it as a renewable process to generate energy while also meeting Net Zero targets. According to the US Energy Information Administration, in 2021, 28 million tonnes of combustible MSW were burnt to produce 13.6 billion kWh of electricity.

India’s own Net Zero plans are equally – if not more – ambitious. As per the revised Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) that reaffirms the country’s commitment to the 2015 Paris Agreement, India has ambitiously voiced its long-term plan of reaching net zero by 2070.

Hitching on the WTE bandwagon and eager to devise technocratic solutions to the country’s waste generation and disposal problems, the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy’s (MNRE) website says that the total estimated energy generation potential from urban and industrial organic waste in India can amount to approximately 5,690 MW.

Further, early last year, as part of Swachh Bharat Mission 2.0, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the scientific processing of waste through WTE plants, which, along with other methods received a budgetary impetus of Rs.1,765 crore.

Read more: Why residents are worried about the upcoming Waste-to-Energy unit in Chikkanagamangala

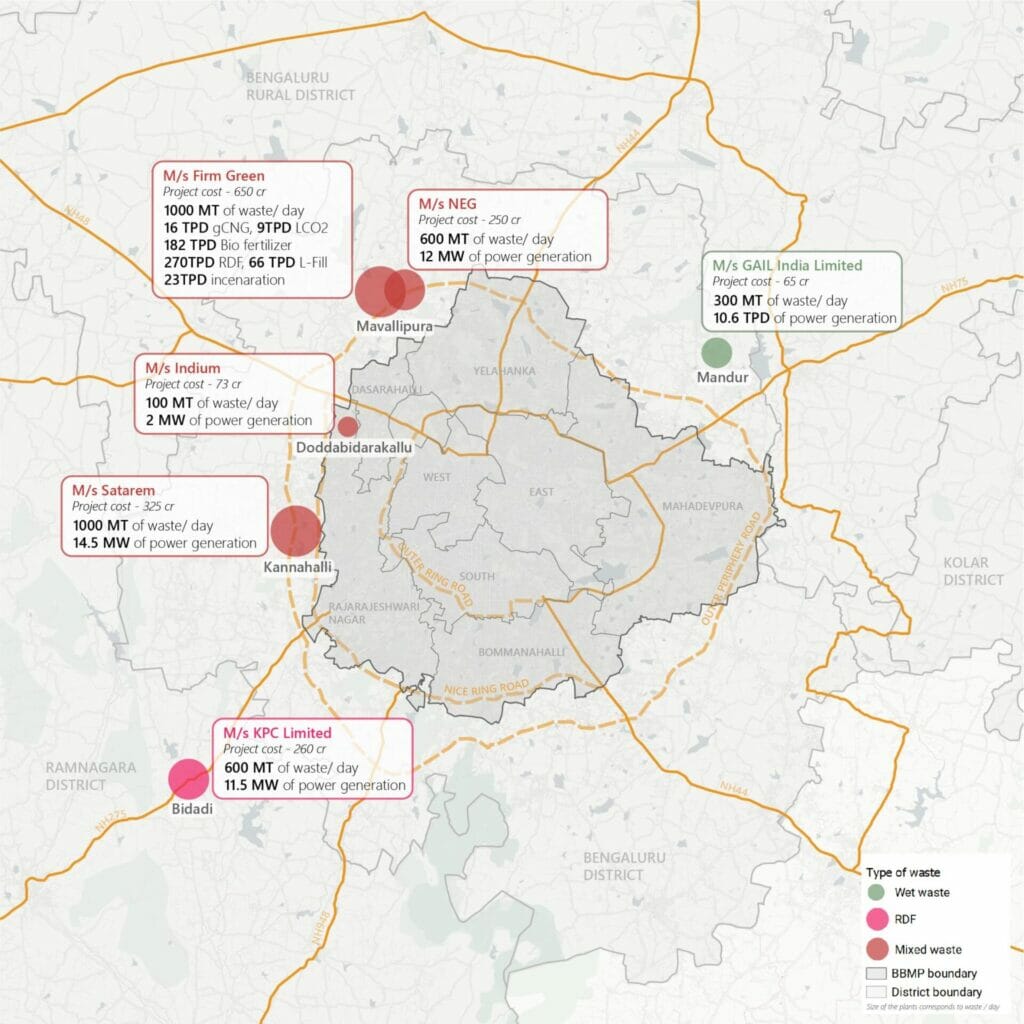

The notion of WTE plants as a silver bullet solution to address Bengaluru’s waste management problem, as well as a way to increase renewable energy production in the city, trickled down to the level of the urban local bodies (ULBs) by 2020, when the municipal authority kicked off the installation of five (six, as of 2022) waste-to-energy plants around the city, based on a public-private partnership (PPP) model.

The Hindu quotes the then law and Parliamentary Affairs Minister J C Madhuswamy apprising the legislative assembly of how these plants would be elemental in facilitating the scientific disposal of solid waste. He was quoted saying that the plants would begin generating power after two years. The first plant costing Rs.260 crore, which came up in Ramanagara’s Bidadi, will have the capacity to process 600 metric tonnes (MT) of waste daily and generate 11.5 kilowatts (KW) of power.

While this seems good on paper, it is a challenging feat to achieve especially in South Asian countries where the composition of waste is different. In a 2019 article in Citizen Matters, author Deepu Chandran states that WTE plants require waste with high calorific value and low moisture content to generate electricity. This means only non-biodegradable, non-recyclable waste is preferred, unlike the mixed waste in India sent to these plants.

“One of the major challenges is waste segregation: the feedstock or the waste that has to be fed into the technology has to be in the right form,” says Dr Suresh NS, a research scientist at the Center for Study of Science, Technology and Policy (CSTEP). In the context of Bengaluru and other major cities, segregation isn’t happening at the source (by citizens in households) and neither is segregated waste being fed into the plants as it should be, claim the experts.

Waste collection in Bengaluru

“WTE conversion processes have the potential to reduce 160 million tons of annual greenhouse gas emissions (and) is expected to cater to 2% of electricity by 2030,” mentions a paper detailing the conversion of waste to energy for a sustainable future. This sounds promising, but may prove to be a tall order, especially for a country like India with a differential composition of waste and the lack of an efficient source or ward-level segregation mechanism.

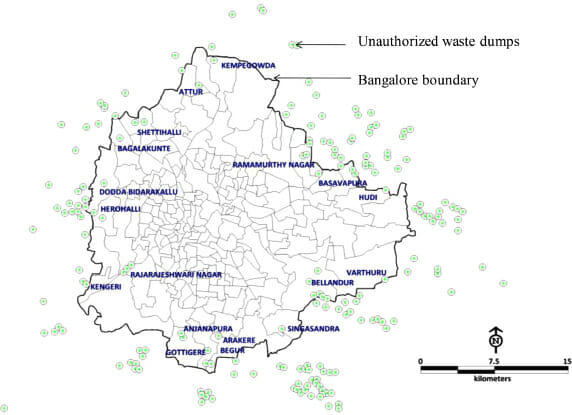

Author BP Naveen in his 2021 comprehensive review of the waste management nexus in Bengaluru, admits that the city “doesn’t have any logical treatment strategy facilities for solid waste.”

The reviewer says, as per the current handling of waste disposal, BBMP oversees 30% of municipal solid waste and administers 70% of the MSW action. The waste per every 1,000 households, is first collected on wheelbarrows or auto tippers to a collection point and is then transported to landfills or waste treatment centres via lorries or compactors.

“Once the waste has been collected and transported, it still has to be segregated. Biodegradables and plastic fractions can be utilised for converting it into useful products such as composting, bio methanation (biogas production), liquid fuels, and refuse-derived fuel (RDF) for heat and power generation,” he says, reiterating that segregation still remains as a primary challenge.

Pushkara SV, a senior consultant at Indian Institute for Human Settlements, agrees. “Only non-recyclable dry waste/RDF fraction of the waste should be sent to these WTE plants. Organic waste has to be sent to composting or bio-methanation plants, eight of which are operated in the city by BBMP, the corporation’s Solid Waste Management officials say. Across the state, 139 MW biomass projects have been installed as of December 2021. Waste consisting of organic material generally has more moisture and less calorific value and hence should not be sent to waste to energy projects for them to operate efficiently.”

Plenty of challenges

Still, despite these challenges, data obtained by Citizen Matters from the office of Rakesh Singh, Additional Chief Secretary, state Urban Development Department, reveals that as of October 6 2022, six plants are in the works in Bengaluru. With a lease period ranging from 20-30 years, the plants have the capacity to process mixed and wet waste and to produce refuse-derived fuel (RDF) that can generate anywhere between 2-14 MW.

The MNRE has mentioned that 216 WTE plants have been set up across the country with an aggregate capacity of 370.45 MW equivalent. Karnataka has 11 WTE plants with an installed capacity of 14.6MW.

But in Bengaluru, none of the WTE plants is currently operational. “There were companies who came forward to spearhead the installation and while they were in various stages of progress, none of them has materialised yet,” says a senior official from the Solid Waste Management division, BBMP, on the condition of anonymity. To elaborate, he says “the companies would enter into Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs), but then demand the revision of power purchase agreements (PPAs), hence stalling or thwarting the operationalisation of these plants,” the official adds.

Sometimes, he mentions, the companies pull out because they haven’t found the right investors or sometimes the deals go sour because they ask for tipping fees, which they would charge to BBMP. “We have to protect the BBMP’s interests as well,” the official states.

Citizen Matters reached out to Satarem (whose plant is proposed to come up in Kannehalli) and 3Wayste for comment but did not receive a response.

An attractive form of renewable energy?

A notification by the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE), dated December 2022, states that India’s total installed capacity of non-fossil sources is 172.72 GW. However, Binit Kumar Das, Deputy programme manager of Renewable Energy at CSE, points out that the 2030 targets don’t clarify the electricity generation specifically from non-fossil fuels.

“Karnataka is in the fourth position when it comes to renewable energy, we have 16GW of installed capacity,” says the Managing Director of of KREDL, KP Rudrappiah. As per the Karnataka Renewable Energy Policy 2022-2027, he says the state has committed to adding 10 GW more during the policy period and hopes this will increase to 20GW by 2030.

The impetus for renewable energy is clear, when one considers that electricity tariffs were revised thrice in 2020 alone, as Citizen Matters earlier reported. The Karnataka Electricity Regulatory Commission (KERC), which is responsible for setting the tariffs, attributed these revisions to “the steep increase in coal prices” and due to “an increase in the variable cost of thermal stations.”

In a notification dated 2016, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MOEFCC) publicised the Solid Waste Management Rules (2016) and mentions that the Ministry of Power through appropriate mechanisms shall “decide tariff or charges for the power generated from the waste to energy plants based on solid waste.”

The rules also mention the explicit or compulsory purchase of power generated from such plants by distribution companies. Further, the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy Sources is tasked with creating infrastructure that will facilitate the plants and provide them with appropriate subsidies or incentives. Officials at KPTCL were unavailable for comment.

According to Rudrappiah, GoK’s New Industrial Policy 2020-25 outlines the kind of incentives that KREDL offers for the installation of these plants. “We do not provide capital subsidies, but offer waivers on concession fees, etc,” he says, to enable the development of WTE plants.

However, the situation on the ground is more complex.

“While Karnataka Power Transmission Corporation Ltd (KPTCL) buys power from the plants, the BBMP is expected to oversee the end-to-end operations like transporting of waste, segregation, etc,” says Pushkara, adding that the shortfalls of operations costs incurred in power generation through waste have also to be absorbed by the BBMP.

According to Atin Biswas, the Programme Director of the Municipal Solid Waste Unit at the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), this makes the plants economically unviable. “When the plants are contracted to private entities, the municipal corporation is tasked with funding the collection and transportation of waste as well as providing tipping fees for plant operators.”

“Unlike in developed countries, the Indian urban local bodies are failing to dedicate adequate funding for waste processing. The waste processing plants generate little revenue, but they should not be expected to make profits,” Pushkara points out. Yet in his view, the BBMP is hoping that these WTE plants will generate some revenue. He says the plants can only generate approximately 25-35% of the operating costs, depending on the scale of operations. According to him, the shortfalls should be paid out by the urban local bodies (ULBs).

For now, and for the foreseeable future, it appears that energy generated from these plants will be more expensive than other forms of renewable energy.

Read more: How Bengalureans can generate rooftop solar power in their homes

Questions on economic viability

In terms of the power purchase agreements between the companies and the plants, “the cost (of energy purchase) for wind or solar is close to Rs.2-4/kWh, which is similar to the rate of power purchased from coal power plants (Rs.2-3/kWh). But for WTE, the cost of power generation is higher which is Rs.6-8/kWh” says Suresh.

KREDL confirms that the tariff at which power is being supplied from the plants is Rs.7.1/kWh, while that of solar is lesser by Rs.5. “This is due to the high capital cost, high operating and maintenance costs, low calorific value and additional fuel required to burn the waste,” explains Binit.

Unlike coal power plants, Suresh claims, WTE plants cannot be boosted to a large scale. “They can be replicated to a few megawatts plants at a maximum, but more than that is not feasible, especially given feedstock availability,” he says. The availability of input or feedstock when it comes to these plants would be a challenge and other sources like solar and wind do not have this problem. Because the capacity of the plants is limited, the cost of energy generation is higher, Suresh clarifies.

According to Binit, while the installed capacity of renewable energy sources across India is 168 GW, WTE’s share is only 250MW.

“While there are WTE projects in the pipeline, (energy generated) from them is minimal compared to solar and wind sources, and hence we are not dependent on them for meeting our (renewable energy) targets,” says KP Rudrappiah.

Still, Binit maintains: “We need to understand that despite its small contribution, WTE plants are required in a well-designed energy mix.” Although solar and wind power are major contributors, there are resources that the WTE plants can tap into to realise their potential, he states.

Deepu Chandran contributed to this article.

This story was produced with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.