In earlier articles, the author traced the journey on the series of constructions on and development of the Outer Ring road (ORR). In part three of the series, the author reflects on whether the flyovers and underpasses in Outer Ring Road benefit everyone, if they really connect Bengalureans, or are meant only to accommodate private vehicles.

This is the third and final part in a series of articles on the constant construction work on Outer Ring Road

Part 1: The ups and downs of Outer Ring Road: A view through the years

Part 2: The ups and downs of Outer Ring Road: Contradictions in infrastructural planning

Road laying

Roads have become sites of political statecraft. One of the first stretches to be white-topped was the Outer Ring Road connecting Mysuru Road to Tumkur Road via Sumanahalli junction. This slowed down the traffic on the signal-free corridor for months. With every speedy intervention, there come multiple phases of maintenance that cause a lag. A few months ago the Sumanahalli flyover gave way and had to be barricaded for repair.

In another instance, trees were cut down to build retaining walls along the entire route to prevent cave-ins during the monsoon and to accommodate larger vehicles (read: trucks) on the service roads. This has led to the Outer Ring Road’s width being narrowed again.

Earlier, there was no safe means of crossing the Outer Ring Road. Now, subways and skywalks have been installed, but they hardly see any footfall since they do not provide the safety that their construction intended. The skywalk step risers are too high and the subways are too dark.

The light in this tunnel, though, is that when private entities take over a stretch of road, they are better maintained. For instance, PES University has been expanding its campus and it decided to maintain the service road as one of the entries to its campus. The road used to be filled with garbage and trucks and is now the alternative route as the Kerekodi junction sees the construction of a flyover.

Read more: Stop building elevated corridors in the city!

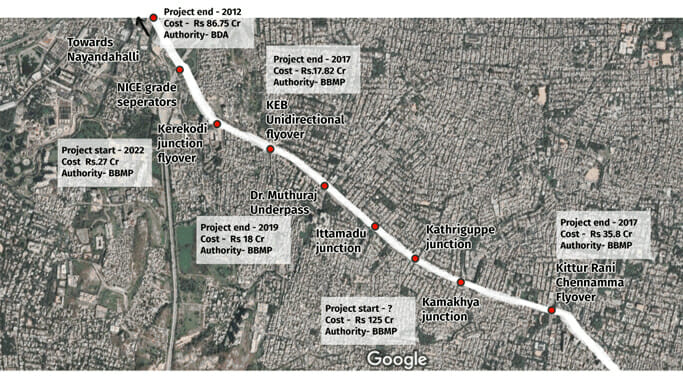

The road fragments us

Construction of flyovers and underpasses are only temporary fixes to a larger systemic problem of a fragmented infrastructural system. According to a study by the Central Road Research Institute (CRRI), titled “gradual sustainability approach for urban transport through subtle measures,” within a few years of construction, such approaches have increased the number of personal vehicles on roads and worsened sustainability without reducing congestion. Such decisions also affect the relationship between the core and the periphery. Pedestrians and public transport will always be on the periphery and private vehicles will be the focus of all planning.

Ostensibly, the addition of new infrastructure will visually reduce the density of vehicles on the road, but in actuality, stricter traffic laws and better road programming and planning will.

Flyovers and underpasses cannot be seen as isolated projects and must be viewed as a part of the overall road network. Bengaluru roads have a radial pattern, which overloads the city centre and causes congestion that spreads outwards, with spillover impacts in peripheral areas.

Architect Prem Chandravarker writes that the strategy should be to relieve traffic flows from the restrictions of this radial emphasis through new concentric connections. One way this could be done is through the proposed Peripheral Ring Road (PRR) and reclassifying existing roads.

Another important planning strategy is to have consistency in road widths, which was an initial design mandate for Bengaluru. It can still be seen in the names of the roads – 100 feet roads and 80 feet roads across the city. The design standards have to be met for better traffic management.

As opposed to the “finished” product of a planner’s map, if we think of infrastructures as unfolding over many different moments with uneven temporalities, not as a linear progression of time and use, we get a picture in which the social and political are as important as the technical and logistical, write anthropologists Nikhil Anand, Hannah Appel, and Akhil Gupta.

What do infrastructures promise? What do infrastructures do? And what does attention to their lives—their construction, use, maintenance, breakdown, their poetics, aesthetics, and form—reveal? How can one critically assess the successes and failures of the Outer Ring Road and the different urban mechanisms that have led us here? How do we view it in all its social, political, and personal intricacies and not just in the technical? After all we, the users, make up the infrastructure too.

Hidden amidst the very Bengalurean behaviour of adjustment, there is a strong memory of all that these roads have borne and a burning hope that the next project will outlive the last and improve mobility, not just in a car but on foot as well. Does the Ring Road truly connect us or is it the easiest ground to play on? Hopefully, the PRR will have a better story to tell.