In a previous article, the author traced the development and series of constructions on Outer Ring Road (ORR), from the 1980s-1990s till 2015, when the Dr Muthuraj underpass was being constructed at Hosakerehalli junction, under the Nagarothana Scheme. Part two of the series will explore how multiple contradictory construction work has affected commuters.

Road repurposing

This has to do with uncertain infrastructure provisioning. Since most of these projects are implemented long after they have been planned or constructed on the go, there are no long-term visions for them. Plans keep changing and there is no one master plan that all these developments follow.

We knew that the series of constructions were part of the signal-free corridor, but we couldn’t see the relation between having any signals and reduction in traffic. The underpass merely kept the view of congested traffic away from our homes. A sense of uncertainty prevails when it comes to any intervention along this stretch. Questions of longevity, maintenance, safety and cost-benefits are something that occupies my mind as I travel through this road everyday.

A lot changed once the underpass became functional. Hidden behind large retaining walls, it makes the city invisible as one seemingly flies through it. The bus stop disappeared along with the main road. We had to walk to the next junction to catch a bus. Two-wheelers were bought in large numbers, in my apartment itself, because of it.

A bakery and an eatery closed shop at the Hosakerehalli junction because they were now on the service road and they hardly saw footfall. Temporary business losses became permanent business losses. Infrastructure affects social integration, accessibility, and inclusiveness.

Read more: Sarjapur Road underpass: Citizens say the ill-conceived project will worsen traffic

According to social scientists Angelo and Hentschel, infrastructure may not necessarily be broken or dysfunctional, but it sometimes evolves or is re-purposed by the local residents to serve different or even multiple functions.

Conversely, they argue, when infrastructure is repurposed or becomes obsolete, its meaning comes up for question, debate, reinvention or reform as well.

Road, redos, and realisations

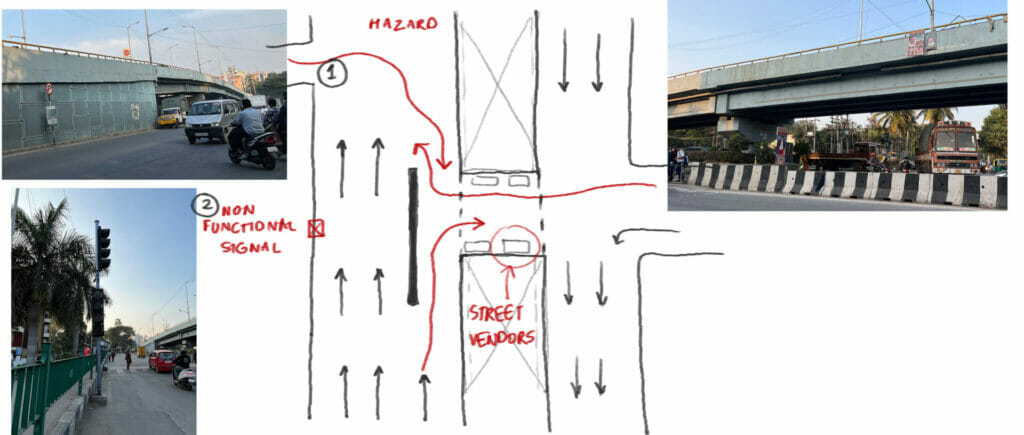

A unidirectional flyover was completed in 2017 at the KEB junction. What happens beneath the flyover is a daily miracle. I have travelled on this road since 2007 and not once was the junction choked. However, since BBMP took it in as part of the signal-free corridor, it was constructed. Although, as soon as it was inaugurated, it was closed for an unreasonable amount of time and began to be used for sand truck parking.

Post the realisation that this did nothing for the Outer Ring Road, two more flyovers were scrapped – one at Ittamadu junction and the second at Kathriguppe junction. Now, BBMP and BMRCL are discussing a combined flyover from Kamakhya to Janatha Bazaar. The resident welfare associations (RWAs) and the residents in BSK 3rd stage were up in arms when the construction went on with no end in sight. When one junction was done, work would be taken up in the next, and the resident commuters gained no benefit. After probing BBMP for the KEB flyover closure, it was reluctantly opened again for public use a year after its completion.

There is always a tense engagement between municipal authorities and the development authority. Add into the mix a special purpose vehicle (SPV) like BMRCL and it creates utter chaos.

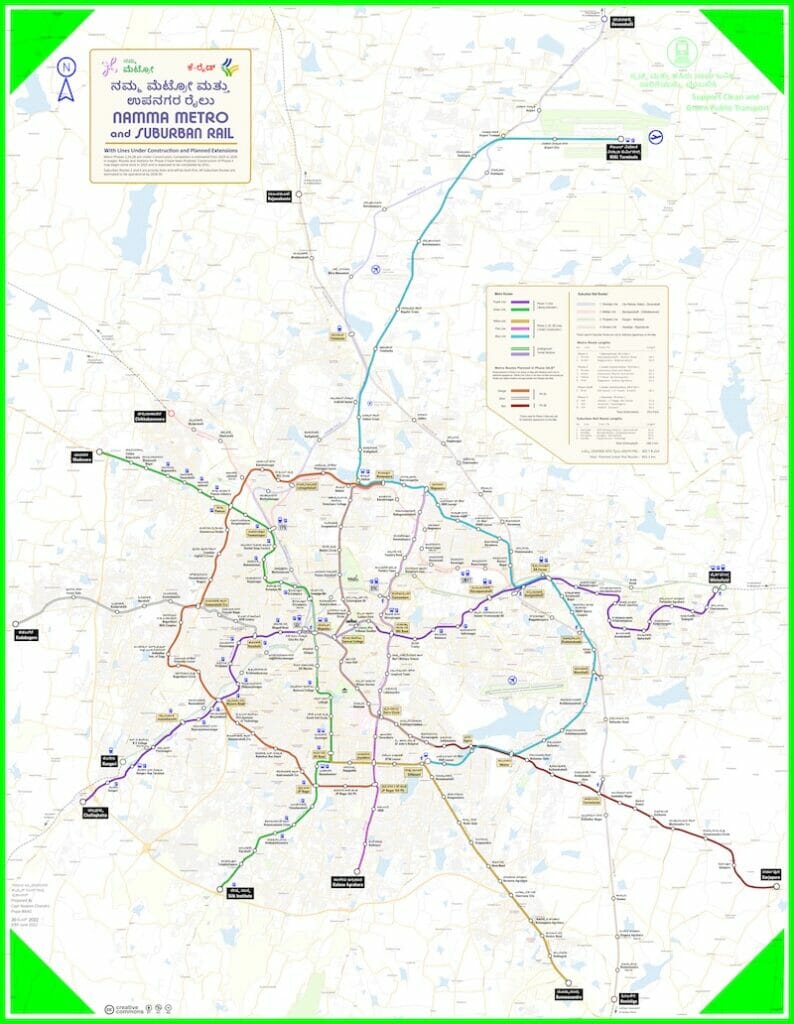

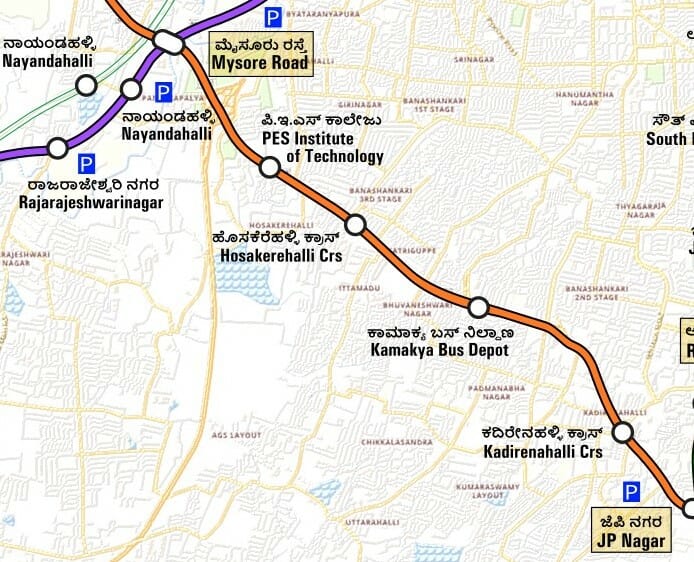

A month after flyover work began at Kerekodi junction (PESU), where barricades were installed and the road dug into, BMRCL stopped BBMP from continuing civil work because the metro line is envisioned on that stretch. According to BMRCL estimates, the project will cost Rs 16,333 crore and is set to be completed by 2028. In September 2022, BMRCL submitted the Detailed Project Report (DPR) for two corridors of Phase 3A project of Namma Metro to the state government for its approval.

Now, as every resident of Bengaluru hopes, I too wish to have a metro station at a walkable distance from my house. But I never imagined that there would be a metro route planned exactly in the stretch, which has been the bed of road construction work for the past ten years.

Phase 3A or the orange line of the metro is planned to connect the purple line of the Mysuru road metro station to the green line of the JP Nagar metro station. So the question on all our minds was if the flyovers and underpasses would have to be demolished like the Jayadeva flyover to make way for the metro line; that too, in less than 15 years since their inauguration. It brings into question what the lifetime of these infrastructures will be?

However, BMRCL issued a statement saying that the alignment of these structures does not pose a problem and that future flyover projects will be shared by BBMP and BMRCL to avoid any potential demolitions.

The Kerekodi flyover is to be a 360 metre, four-lane one, built at the cost of Rs 20 crores. As any person with a remote sense of proportion can assess, the KEB junction flyover and the Dr Muthuraj junction underpass will not align with an elevated metro line. Four years were spent in constructing it and in all likelihood in the next eight, it will be replaced. Assessments are still underway by BMRCL to verify the two grade separators that do pose issues in alignment with the proposed metro line.

Who is answerable for all these contradictions in our infrastructural planning and how do we hold them accountable? If infrastructural governance mechanisms are not decentralised, the picture on the ground will be starkly different from the planner’s sketch.

The Karnataka government, in September 2022, tabled a Bill to set up the Bengaluru Metropolitan Land Transport Authority (BMLTA) for Urban Mobility Region in the city by integrating functions of existing multiple civic agencies and departments into a proposed new authority for promoting seamless mobility. Consequently, DULT’S comprehensive mobility plan, created in 2020, will have to look into integrating all the modes of public transport with private circulation. The hope is that this will change the way roads have been planned in the city.

The design of transportation systems should be in tandem with the comprehensive master plan. These infrastructural developments have been divorced from the preparation of the CDP and there continues to be no finalised masterplan out in the public yet. So all these infrastructures under discussion are built off the air.

[This is the second part in a series of articles on the constant construction work on Outer Ring Road]

This writeup has raised some really good questions about transport infrastructure development without a holistic approach, as summarized in the last paragraph. There is however a point raised that is out of context – that of retaining walls blocking views at Dr Muthuraj junction underpass. All underpasses would have to have retaining walls that would block views and Dr Muthuraj junction underpass isn’t an exception. The view of the terrain above is of less importance to motorists using the underpass whose attention needs to be on safely negotiating the slopped road through the underpass. Even if views of the exterior can somehow be arranged to the drivers passing below, it would be distractive and can even be unsafe if drivers shift their attention.

To me, the “retaining wall blocking view” looks more like just a mention, to evoke similarity with “sweeping under the carpet”.

The main concerns of the article – Poor planning and execution really call for very well thought out action plan.

I want to add three points here:

1. How is it that Bangalore infrastructure projects take such long time? Is it lack of planning? Or lack of proper management? There is one flyover in chord road, which is under construction for nearly a decade and still not complete (between Tollgate and Navarang underpasses)

2. If we quantify ALL the costs – environment, health, delayed execution (and not only the construction costs) is underground Metro really prohibitively expensive in comparison?

3. Why can’t a bypass system built properly, before any road project starts?

Apart from the needless whining about views being ruined because of the retaining walls and the contradictory stance of feeling sorry for a family that was carrying out their business near the underpass but complaining about a cart under the KEB flyover, valid points were raised.