Bengaluru recently topped the TomTom Traffic Index 2019, that ranked 416 global cities on traffic congestion. Mumbai (4th position), Pune (5th) and Delhi (8th) were the other Indian cities that featured in the top 10.

Countless memes and jokes on Bengaluru’s notorious traffic and roads – most recently the ‘astronaut walking on moon’ video – have been doing the rounds. Why is the city unable to solve its traffic mess despite its countless planning documents and experts?

Only 7% land in Bengaluru is used for road infrastructure

Bengaluru is a ring-radial patterned city similar to Delhi, Hyderabad and Ahmedabad. The disadvantage of a ring-radial patterned city – especially if it doesn’t have a well-formed grid network – is long travel times, compared to a linear city which has shorter travel times for the same distance (eg., Mumbai, Chennai and Kolkata).

The draft Revised Master Plan 2031 (RMP 2031) documented that 7.39% of Bengaluru’s land use was for transport (which includes roads and other transport-related infrastructure). One may argue this is relatively low when compared to, say 21% in Delhi (though Delhi has its own share of traffic issues in spite of its wide road network).

Various planning guidelines like the Urban and Regional Development Plans Formulation and Implementation (URDPFI), also prescribe between 10-15% land use for road infrastructure in any metropolitan city.

Bengaluru, as we know it today, is a combination of villages consumed by the city’s metabolism. The average road width in the city is just 15 m or 50 ft, which is inadequate even to augment it with any form of public transport. For example, a cost-effective BRTS (Bus Rapid Transit System) requires minimum road width of 36 m. All arterial roads are also supposed to have a minimum width of 36 m, but here, even in certain ORR stretches (such as the famous Udupi Garden, BTM), the road suddenly narrows, leading to traffic jams.

City has little control over land use

For decades now, Bengaluru has been attempting to emulate Singapore. This can be traced back to the reign of ex-Chief Minister S M Krishna and BDA chief Jaykar Jerome in the late 90s. The Singapore narrative has been used time and again to evoke the urban spectacle.

But there is limited understanding of how Singapore implements such mega infrastructure – the government has maximum control and ownership of land. It chooses how to control land use and supply. This is almost an ideal situation for planning that has manifested in a highly-controlled urban environment.

Even though our planning policies can be made to replicate western paradigms, our land assemblage and ownership models are very different and complex. Bengaluru, outside of its core, is largely a privately-owned and developed city.

Post-liberalisation in the 1990s, planning was left to market forces, and automatically, self-interest pushed maximum urbanisation around existing infrastructure. There was also clear interference by the private sector and civil society to push policy and planning in their favour.

This, in a sense, led to the co-option of the state by private actors and civil society, thereby turning planning into a political tool rather than a technical tool, and planners their biggest scapegoats.

Unwillingness to relinquish land stalled road development in new areas

Post-independence, we adopted a hybrid concoction of Soviet and American style planning, which was pivoted on segregation of land uses. For decades now, failure of the city’s transport networks and infrastructure has been termed very simplistically as the failure of urban planning. Numerous urban evangelists have termed this as “a failure of enforcement and implementation”.

But if you dig deeper, you’ll realise that, in many cases, the land for roads have not been relinquished by landowners and developers, or that development has taken place over the proposed roads. Also, due to the gated nature of majority of our development, many roads are trapped within siloed layouts.

The city has been characterised for ages now by illegal development, and governance has been reduced to appeasement politics with policies like Akrama-Sakrama. These issues have snowballed into the lack of road networks.

A classic case of this is Whitefield – there is literally one road to go in and out of Whitefield, which has led to chronic traffic jams at Hoodi and Kundanahalli junctions. The implementation of Phase 2 of Metro is lagging primarily because the city has narrow roads (take the Cantonment/ Tannery Road debacle for instance) and land acquisition is a herculean task.

The failure to act collectively and put public interests over private – such as the failure of private owners to relinquish land, governments’ failure in implementing/enforcing road networks – has come back to bite us in the form of traffic and other chronic urban problems.

Town Planning schemes as implemented in Gujarat offer solutions to these complex land acquisition issues, even though these are time-consuming procedures. Instead of acquiring individual land parcels that disadvantage land owners, Gujarat adopted the area development approach. But to implement this in Bengaluru, the existing Karnataka Town and Country Planning Act needs to be amended.

Draft RMP 2031 does attempt to address Bengaluru’s traffic issues

The draft RMP 2031, released in November 2017, is a layered planning document which introduced a number of paradigm shifts in urban planning. It created a robust GIS database (cadastral data and even 3D of the entire city!) and allowed for the preparation of Local Area Plans.

More importantly, it was the first master plan in the country to calibrate a four-stage transport model with the land use plan. Never had such an exercise been conducted for the city. It proposed a robust hierarchical road network, and layered the public transport network over the arterial road network (Page 103 in the document).

The plan set the ambitious target of achieving 70% modal share in public transport, incrementally by 2031. It didn’t subscribe to the flyover approach either. It also identified key projects to be taken up on priority to ease traffic.

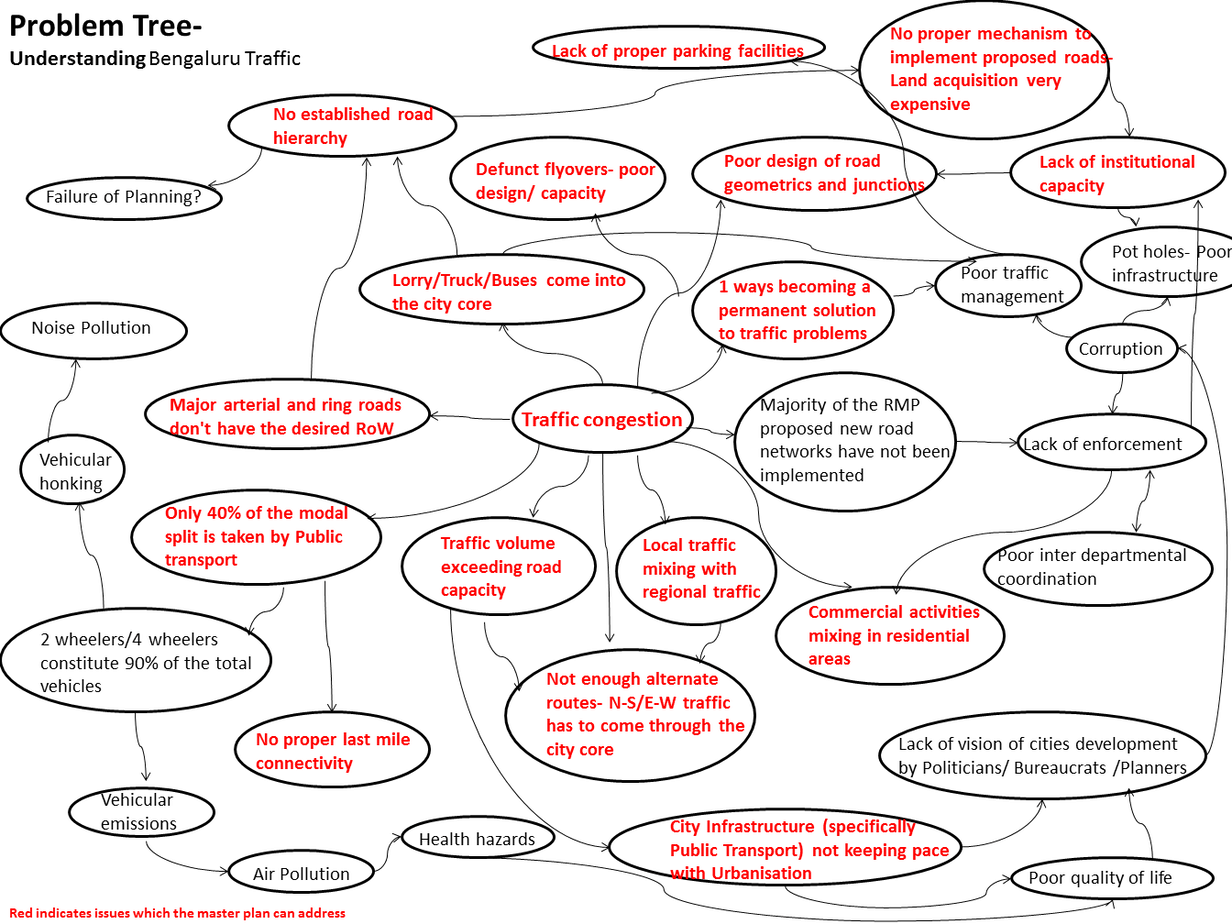

The text highlighted in red indicates traffic problems that the RMP 2031 can address. Image: Benjamin Mathews John

Public participation was built into the entire planning process, even before the final plan was readied. There were a number of positive ingredients in the plan if one was interested in taking it forward.

The failure to finalise the draft RMP 2031 has definitely led to policy paralysis of the city and a waste of taxpayers’ money. We didn’t seem to want to move constructively beyond the question of who should plan for Bengaluru – the Metropolitan Planning Committee (MPC) or the Bangalore Development Authority (BDA).

How do we solve this traffic mess now?

What is fundamental to solving Bengaluru’s transport problems is the need to look at the city and its transportation networks in an integrated manner. Thus, for quite some time now, many pundits have been calling for the formation a Unified Metropolitan Transport Authority (UMTA), similar to the LTA (Land Transport Authority) in Singapore or TFL (Transport for London) in London.

Is the Directorate of Urban Land Transport (DULT) playing that role? At least it seems they are trying to.

Another question we must ask – are organisations like BMRCL (Bangalore Metro Rail Corporation Ltd) or BMTC (Bangalore Metropolitan Transport Corporation) ready to collaborate and follow the UMTA? Governance needs to move from the existing ‘durbar’ format and become more collaborative.

What should transport authorities focus on?

- Move from land use planning to outcome-based strategic planning that’s centred on area-based development and public participation. Master Plans should be dynamic and flexible documents that can adapt to changing times and technology. For this, as mentioned earlier, we need to first update our archaic Town and Country Planning Act.

- One of the mandates of the NUTP (National Urban Transport Policy) 2006 was to set up the UMTA. Setting up an UMTA is going to be a huge value-add to the city in terms of adopting an integrated approach to solving mobility issues. If set up, UMTA must create a system in which various departments like BMRCL and BMTC work together, and where the UMTA doesn’t function like a big daddy.

- I understand that car purchasing is still aspirational in our country. But we must have a policy where people are taxed heavily if they wish to buy a second car (But do we have the political will for this?). This policy should be adopted at the national level. Also, when people buy a car, they must have a designated parking space for it in their homes.

- Explore the possibility of congestion pricing, especially for the city centre.

- Put the onus on employers to make sure their employees use public transport; the costs should be borne by the employer.

- Create more options for public transport – BRTS, Suburban Rail, LRTS, etc, rather than the outlandish POD idea. Along the ORR, there must be one mass transit station every 500 m. Glad the dedicated bus lanes are working well.

- The future is shared mobility – make policies that ease the functioning of shared transport like Zipgo.

- Create more infrastructure for pedestrians and cyclists at the neighborhood level and around mass transit stations.

What can we do as citizens?

- In a large city like Bengaluru, it’s nearly impossible to live close to work (as land values don’t allow you to), but if you can, please do it!

- Demand that authorities provide more seamless, comfortable public transport options and improve last-mile connectivity.

- CEOs need to get out of this fancy that they need a chauffeur-driven car, and start using public transport.

- Walk as much as possible; take your car out only if you really need to. If you can give up your car or two-wheeler, do so!

- Opt for share-cabs, carpools.

- Use public transport, autos, and cab aggregators like Ola and Uber, as much as possible.

- Don’t depend heavily on aggregators to get your daily supplies; walking down to the nearest grocery store won’t hurt. New studies have shown that app-based delivery services tend to increase traffic due to a large number of trips for delivering singular goods.

Also Read:

- London’s transport chief on solving Bengaluru’s traffic woes: Plan for public transit and dense city core

- Understanding BDA Revised Master Plan 2031: A series of 9 webinars to help Bengalureans understand BDA’s proposed Master Plan

Well articulate.

Few points missed out

1.Protuct and safegaurd our goverment investments ,considering it as ours…Ye Apna hai

2. Follow traffic rules, it eases our journey.

3.Put safety ahead of everything

4.Using facilities already provided. 5.Particapate reponsibly by doing your duties as responsible citizen.

6.Drive cleanliness and help to beautify the place ,just spend few hours of your holiday time in doing it

7. Interact with local authorities to understand various issues and help in providing solution by your contributions.

This will definitely Transform Bangalore into a better place to live

We need set standards by doing for Banglore to be Beautiful and restore it’s unique identity.

Best way to reduce traffic is by stopping people coming from other states.

So that less people means less vehicles and less vehicles means less traffic.

To stop people from migration, give reservation for local people. Shift some of the software companies to other states like UP,Bihar ,AP ,orissa.So that even revenues of these respective states increases.

Excellent analysis Benji.How to solve the problem is the matter on which we need to put our heads together!!!