A high-decibel campaign followed by exit poll bets and now onto resort drama? Political pundits exclaimed it was a “waveless” election and it was hard to predict who would win. Exit polls predicted both ways, though the majority predicted a small lead for the BJP. Bettings favoured the BJP, while stock market rallied predicting a BJP victory. But what did this election mean to the citizens of Bengaluru?

On one hand you had Siddaramaiah who had launched a number of welfare schemes targeting the poor and on the other side, a prime minister seen as a decisive ruler with bold schemes like GST and demonetisation. One side, a push for a separate religion for Lingayats, on the other side, an aggressive campaign by Modi and his colleagues from the North, pushing a Hindutva narrative.

What worked eventually?

The undercurrent seems to be money power, which helped pay for high profile campaigns, and for focusing on booth-level targeting of voters. What’s more, the practice of distributing freebies and cash is now well institutionalised, with most sitting MLAs resorting to distributing gifts much before the election got declared, and wooing the gullible voters with money even during the elections. Many voters in slums who were given cash were told their individual votes were tracked, and were bullied into following the diktats on who to vote for.

Voting pattern in Karnataka doesn’t seem to have been influenced by the work done by individual MLAs. Then what did influence the trend?

Corruption wasn’t a factor to voters

There were newfangled parties like Swaraj India and Aam Aadmi Party, who fielded their candidates, hoping that educated and connected people in cities like Bengaluru might want a change. Most of these candidates ultimately lost their deposits, let alone making a mark. The typical urban voter didn’t care enough.

Renuka Vishwanath, a former IAS officer standing as an AAP candidate, got a mere 2858 votes. Others got even less. Darshan Puttannaiah, son of late Puttannaiah, a very popular farmer leader, was able to get 73,779 votes, but still lost by a margin of 22,224 in the old Mysore region, a Vokkaliga belt that preferred the JD(S).

Whether it was the mining barons or those accused in scams, none of the parties shied away from giving them tickets and voters didn’t mind making them their choice. An analysis by ADR shows there are 77 winners with declared criminal cases — 35% of the winners are in conflict with law.

Bhamy Shenoy, member of the citizen forum, Mysore Grahakara Parishad, is emphatic: “Corruption was not a factor. Development was not a factor.“ He points that Chamaraja constituency in Mysore did not reward sitting MLA Vasu who is known to be a good MLA, while the winner Nagendra (BJP) is a former MUDA chairman responsible for a disastrous master plan for Mysore.

In Hubli Dharwad, Congress MLA Vinay Kulkarni, who was the Minister for Mines and Geology, lost by a margin of more than 20,000 votes. Ottilie Anban Kumar, a citizen activist in Hubli – Dharwad, says the margin was surprising because he was seen as approachable and responsive to citizens. However, he was one of the main leaders in the fight for a separate Lingayat religion and thus was successfully painted as a divisive force.

Dakshina Kannada, that gave 7 MLAs to Congress’s winning combination in 2013 along with a few seats to independent and JDS, saw a reversal of trend this time. In Mangaluru, former Corporation Commissioner J R Lobo lost in the BJP wave, even though he is said to have performed well. Journalist Harsha Raj Gatty points out the coastal belt is known for its inclination to vote along communal lines. He says: “Congress as a brand does not work here.” He says unlike Bengaluru, Mangaluru has no citizen-driven agenda drawing attention to developmental issues during elections, with environmentalists and activists seen as fringe elements.

So did Bengaluru fare better because there were citizen activists?

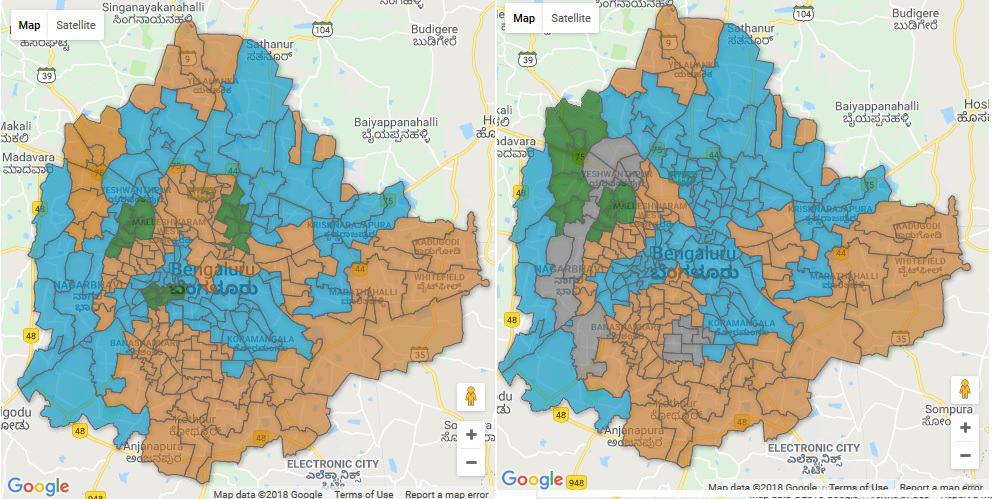

How did Bengaluru vote?

Cities like Bengaluru are high on civic activism, and citizen groups here understand how evaluate MLAs based on their performance in assembly including questions asked and debates, and how to evaluate candidates too. Despite this, Bengaluru as a collective voting force chose to re-elect some of the non-performing MLAs who took control of the municipal work, multiplied their wealth in five years, but did not care enough about what they had to do in the assembly. While there have been cases of good performing MLAs getting elected, the margins have been lower than the margins of richer and more powerful MLAs of the city.

A large number of voters let caste and ideological considerations influence their decision. Many voters also fell for WhatsApp-based propaganda and fake news. Their choice for the large part did not reflect the performance of the sitting MLAs in any way.

The coastal areas, where Congress has been wiped out this time shows incumbency was not a factor too. Most party manifestos were released in the last few days, and voters don’t seem to have given any importance to that. There was little conversation about larger governance and policy issues.

Shenoy laments, “Election is no more part of democracy”. While educated are indifferent, the poor are not in a position to cast a discerning vote.

A progressive citizens’ approach to emulate

Meanwhile, Bengaluru saw a more progressive discourse in the run up to the elections. Many residents’ associations and citizen groups have been active in putting out their own charters, engaging with candidates, and urging more people to vote. They played a non-partisan role, urging citizens to vote for candidates and not the party or other considerations. Their demands have been very focused on civic and development issues like public transport, empowered ward committees, fixing polluted lakes, etc.

Candidates signing the Mahadevapura charter. Pic: Murali G

While Bengaluru for the most part voted in the incumbents, even the RWAs frustrated with their unresponsive elected representatives, have remained steadfastly apolitical.

Srinivas Alavilli, one of the active citizens who initiated the Citizens for Bengaluru group, says their strategy is party-proof. “We have been quite successful in pitching our demands to all parties and insisting on including them. No matter who forms the government, the agenda for the city is already in their manifesto and we get to hold them accountable.” The group Citizens for Bengaluru had prepared a citizens’ agenda which reflected what citizens want on policy and infrastructure front. Many of these demands found a place in the manifestos of the political parties.

These groups not only intend to engage with the elected representatives, work with them and hold them accountable, but are also looking to spread the spirit of democracy where candidates are judged not through narrow sectarian prisms, but on their own merits and how best they represent their constituents and make their lives better.

This approach is one that needs to spread across Karnataka and the country, if we have to become a more enlightened democracy.

Note: This was published first on Indian Express.