In July 2021, Brookefields Layout, a community East of Marathahalli in Bengaluru, finally got its roads asphalted. Within a month, BESCOM – the electric utility, informed the community that they wanted to dig a beautiful, brand-new road to lay their 11KV lines.

Prior to asphalting, we had asked several utilities (including BESCOM) if they had any pending work on the road. Many took the opportunity to lay their lines; the road asphalting itself was delayed to accommodate new gas lines, optical cables, telephone cables, water lines, and more. BESCOM said they had no plans; for them to now say they wanted to uproot the road was more than callous, it was more than a waste of tax money; it was a stab in our back.

This digging, trenching, and gashing of new roads is, unfortunately, a common and a very frustrating experience.

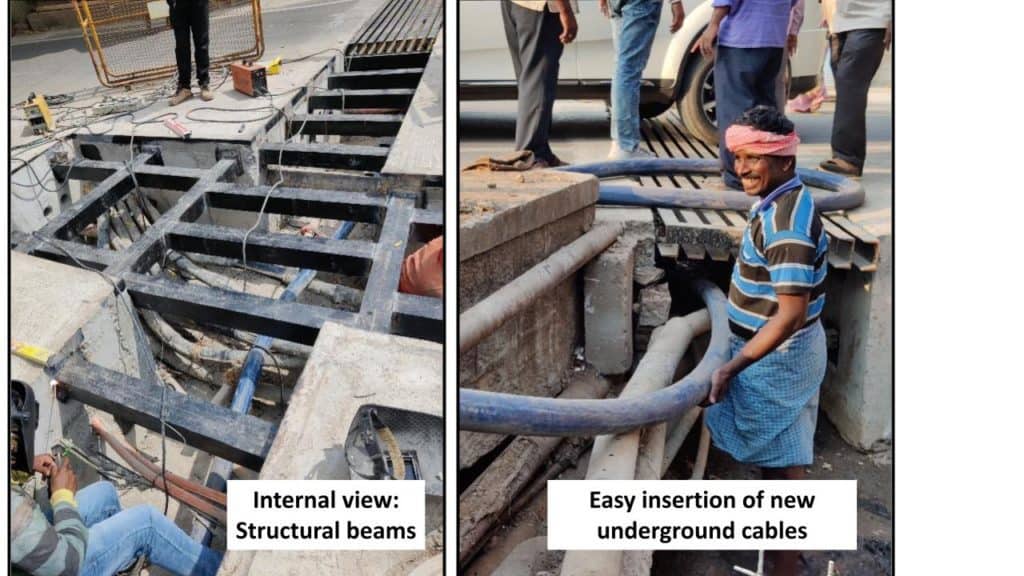

Talks with BESCOM to get them to install a cable duct, one that can easily be opened to facilitate maintenance and installation of new cables, failed. BESCOM stated that they have never made cable ducts and had no plans of making one. We resolved to crowd-fund and build our own duct.

The municipal authority, BBMP at first dithered over granting permission for our proposed cable duct, involving, as it did, excavation along a major thoroughfare. A call from our MLA produced the requisite approvals from the officers. There is no shortage of engineering talent in our community. An email with a design proposal and estimated funds (Rupees 5.5 lakhs) went out. Within a week, we exceeded the collections target, having crowdsourced Rs. 7.75 lakhs. A Bhoomi Pooja later, we started excavating. Policemen who enquired about our excavation went away quietly when they saw our permission letters.

Our original design was found insufficient to bear the load of the massive 60-tonne concrete mixers that ply down that road. We persevered, requesting more funds. Then the Ukraine war started and steel went up by 30%. BESCOM came in and demanded an expansion of the scope of the project on the grounds that they needed access to adjacent underground cables as well. A third fund-raising round took place.

A six-week project dragged on for two months and experienced a 100% cost overrun, BUT, it got done! A well-engineered, citizen-funded duct-culvert that already hosts two new cables (and is expected to shortly add three more). One that enables easy entrance of maintenance workers, one that drains rainwater away before it floods the locality. A point of pride for a community that believes in self-sufficiency and takes self-governance very seriously.

The average citizen who wants to get a pot-hole fixed runs from pillar to post in the byzantine municipal bureaucracy, begs politicians, raises a Twitter storm, sometimes organises a protest. And, then, at long last, when gets the job done (if at all), the quality is iffy, his hair has greyed, and frustration has sapped his strength.

For citizens, improving or maintaining public spaces and amenities in India is frustrating, demoralising, disempowering, enslaving and degrading.

Read more: Gottigere ward walkability report, a citizen’s survey and perspective

There is, however, a simpler and alternate way to get things done

At Brookefields Layout, Bengaluru, we formed the Brookefields Layout Residents (BLR) Association, itself a federation of apartment associations. In contrast to the traditional residents’ welfare associations (RWA), the BLR Association collects voluntary funds from residents and undertakes public works.

From these internally raised monies alone, BLR has established sidewalks, lit dim streets, transplanted trees to widen roads, planted new trees, installed openable covers to enable regular drain-cleaning, fixed underground water leaks, filled potholes, banished a chronic flooding problem, and employs a permanent staff of four to clean the street and the drains every day.

The results have been remarkable. What was once a narrow, filthy, odoriferous, pot-hole-ridden, sewage-flooded, poorly lit, traffic-jammed, Mofussil dirt road now sports two wide vehicular lanes, a bollard-protected pedestrian pathway almost as wide as a car lane, functioning streetlights and drains that almost never choke or spillover.

Beyond the obvious improvement in the standards of public space, there has been a marked improvement in the relationship of the residents with their neighbourhood. They now feel that there is not only a viable pathway to escalating a public grievance but also a viable funding system to resolving that public grievance.

Our RWA’s only goal is upholding and maintaining the standards of public spaces.

Any good idea from residents for urban improvement gets a fair hearing. Having a self-financed pot of money to spend on local activities, the people don’t have to beg an officer or politician to get small works done.

Kirana-shop owners, notorious for messing up the surroundings, cooperate in keeping the area clean. Dog owners take their dogs to designated pooping areas. Pedestrians generally walk behind bollards. Visitors understand that the area is not to be messed with. Local labourers, gardeners, masons, and metal workers get jobs without the overhead of kickbacks and bribes to petty officials.

Read more: How Sanjay Nagar residents are using a 20 lakh ward grant to improve their footpaths

This is empowerment

How much does this all cost? And do we enforce collection? Second question first: we do not enforce collection. Contributing is entirely voluntary. Also, we don’t generally collect directly from the residents, but from their apartment associations, in proportion to their number of dwelling units.

From the nearly 1,500 dwelling units, we manage a monthly collection of about Rs 70,000, or, on average, just Rs 50 per month per dwelling unit. Aside from monthly voluntary contributions, we also run periodic fundraisers for various public causes — the installation of a culvert, the installation of bollards, clearing debris to create a footwalk, the installation of streetlights, the payment of a medical bill for a labourer, the tuition fees for another labourer’s daughter, Ugadi gifts and repasts to labourers.

These fundraisers raise anywhere between Rs 15,000 to Rs 10 lakhs (typically, Rs 200 to Rs 20,000 per individual, again on a voluntary basis).

Everybody knows, sometimes very personally, the people who are requesting the funds. Therefore, the fundraisers dare not be corrupt. Social pressure thus is a natural back-stop against corruption, a mechanism conspicuous by its absence in governments.

The concept of self-funded (or self-taxed) neighbourhood improvement is hardly new. The New England states of America have long had their selectmen and alderwomen, a much-admired system of local taxation and governance. Closer to home, Mahatma Gandhi spoke about panchayat raj, i.e., a system of local governance in which each village is responsible for its own affairs. “Independence begins at the bottom… A society must be built in which every village has to be self-sustained and capable of managing its own affairs … This does not exclude dependence on and willing help from neighbours or from the world,” Gandhi wrote.

Must we, therefore, be dependent on large centralised bureaucracies to lift ourselves out of our miseries? Can we not organise small, village-level teams to do the same, with more people’s involvement and at a dramatically lower cost?

Am I suggesting that localities self-organise and self-fund themselves? Absolutely. But what I really want to push for is the need for legislative support for RWAs, area sabhas or similar organisations.

- A law that directly funds apolitical neighbourhood organisations with a proven track record of public service and public works, or,

- An amendment in the income tax code enables a taxpayer to specify that a fraction of his/her taxes be directly routed to the ward committee. A law that enables local bodies to raise their own taxes alongside a more-than-proportional decline in central taxes.

Such laws would not only financially empower urban ward committees and ordinary citizens, but they would also do so in a hyperlocal and apolitical fashion. Grassroots democracy is meaningless without grassroots financial empowerment.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Are you suggesting a parallel government (even if only a local one) to replace the central-state-74th-amendment system of government?

No. To be clear, we are not against central or state investment in localities; indeed central and state urban investments should be a continuing feature of governance, especially in critical and vast urban infrastructure projects like a metro system. What we’re arguing is that citizens of a given neighbourhood best know what is good for their neighbourhood, and they must be financially empowered (or they must financially empower themselves) to fix their hyperlocal issues. We are of the opinion that no central authority should do what can be done by a more local body.

- What about the taxes I already pay to the government? Shouldn’t they be used to fix my neighbourhood?

The taxes you pay go straight to New Delhi or your state’s capital. There is no local, i.e., ward committee-level taxes, and property taxes collected by municipalities are minuscule. Therefore, sending your taxes to New Delhi and then complaining that your garbage is unpicked is a fool’s errand. I estimate that by localities taking care of their own neighbourhoods, central taxes can be cut by 50% or more.

- But aren’t we taxed enough already? Local taxation can only add to our burdens.

I do not suggest adding to taxes, rather, increasing the fraction of taxes that flow to neighbourhoods by enabling taxpayers to specify a portion of their central (or state or property) taxes to flow directly to their area sabha or ward committee. An increase in local taxation can actually decrease the overall tax burden. Local taxation (or self-funding) is efficient, uncorrupt, transparent, unbureaucratic, un politicised and responsive to local needs. Central taxes are none-of-the-above. Also, the effects of local taxes (or self-funding) are more visible, can create trust, at least in local institutions, and widen the effective tax base.

- Why should localities spend and do the work of the government?

We, individual citizens, want the chance to be able to directly fix our locality’s problems rather than spend time chasing government departments. Who knows a locality better than its residents?

Citizen initiatives, even if crowd-funded, do not reduce the relevance and role of central, state, and city governments. Small spending by localities will not shut down the city government. All hands and funds are needed to build and maintain society.

- Shouldn’t private citizens spend their time making the government more accountable than doing privately-funded neighbourhood improvements?

By all means, please continue to make the government accountable. Self-funding (and local taxation) is one more arrow in the quiver. And a formidable one.

Are the middle class not paying enough tax today? Why can’t a small portion of my tax be allocated to develop my area where I live in.

I havnt read a more sensible article in a long time, an enterprising step in the right direction and one that many of us from other woe begotten localities in Bangalore and perhaps India, must seriously look at to solve critical issu s like flooding every year and road digging which has become a most unamusing joke.

I never thought my 200rs contribution every month goes a long way! Great effort effort Arvind! Very proud of our community.

Great article. Definitely awesome to see you and the residents take ownership and do so much in this better and more economical way. Just the before and after photos tell so much of this wonderful story. ✌

I am deeply moved that you and your association is doing the things that otherwise a sensible government would be doing. Instead of complaining and getting nothing done, your team is being proactive and proving that self-help is the best help.

My deep respect.