Over the years, the water bodies in Chennai and across the state have been polluted and damaged due to many reasons including rapid urbanisation and encroachments. Time and again, the restoration work being carried out in these water bodies make it to the news. Often, the local bodies rope in Non-Governmental Organisations to oversee or carry out either the entire or some portions of the restoration work. This apart, many private companies also chip in with Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) funds to carry out restoration work.

While the restoration work is carried out by different agencies at different places, there are no guidelines or standard methodology for ecological restoration to ensure that a systematic and scientific approach is followed. Efforts are also not taken to ensure the sustainability of impact. This leaves different agencies to follow different approaches depending on the level of expertise they have on the subject.

What are the existing guidelines?

Though there is no standard methodology prescribed for water body restorations as such, the Central Pollution Control Board, in 2019, published the Indicative Guidelines for Restoration of Water Bodies in compliance with an National Green Tribunal (NGT) order.

Following this, the Tamil Nadu government also came up with an action plan in 2019 adopting the said guidelines. The indicative guidelines were framed with an intention to make pollution-free water bodies, meet the desired water quality criteria, preserve excess water during monsoon, restore and augment storage capacities of water bodies, serve and enhance groundwater recharge and increase the availability of water for different intended purposes.

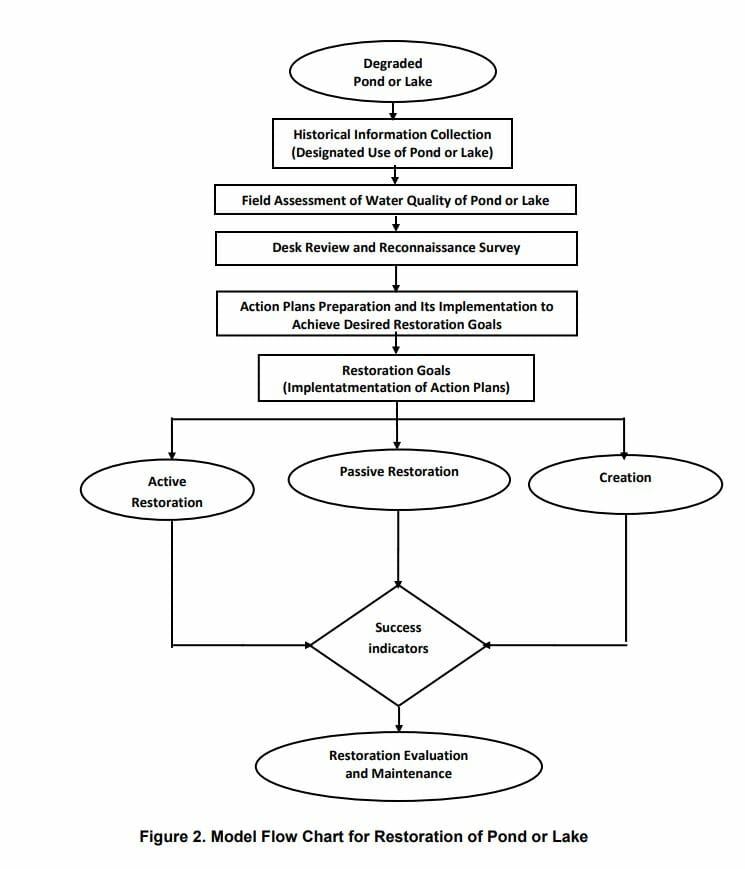

According to the indicative guidelines, the restoration activities are envisaged under five phases namely the recognition phase, restoration phase, protection phase, improvement phase and sustenance phase.

The activities to be carried out under each of these stages are as follows

Recognition phase

- Collection and maintenance of historical, geographical and hydrological information related to the water bodies

- Catchment description of the water body

- Digital mapping of all the collected information

Restoration/gap analysis phase

- Identification of ‘Designated use of water body’ through assessment of the water quality

- Identification of sources of pollution, quantification and assessing detailed gap analysis (sewage management, waste management, industrial effluent management)

- Identification of any other issues that require attention

Protection phase/planning and DPR preparation stage

- Preparation for action plans for waste management

- De-silting

- De-weeding

- Mechanical and biological control measures

- Prohibition of discharges, waste disposal, washing activities and action against violators

- Stabilisation of earthen bunds and the drainage channels along with silt and soil erosion control measures

- Protection of drainage basin, removal of encroachments and blockages and flood control measures

Improvement phase

- Adoption of in-situ techniques for in-situ remediation

- Drainage basin management

- Creation of green or buffer zone

- Creation of biodiversity environment

- Monitoring the implementation of action plans

Sustenance phase

- Creation of awareness among citizen’s groups, residents welfare associations, local organisations, activists groups, green organisations, political organisations, educational organisations and government agencies

- Organising periodic trainings through identified and reputed institutions

- Promoting public participation

- Dissemination of information

- Creation of recreational centres

These guidelines are only indicative and are limited to the restoration of ponds, lakes, polluted rivers or streams. However, concerned stakeholders are advised to conduct a detailed gap analysis and include related action plans for the restoration of water bodies.

Read more: Thazhambur Lake restoration brings fresh lease of life to the area

What methods do different organisations follow?

Jayshree Vencatesan, the Managing Trustee of Care Earth Trust, who works on the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity and ecological restoration of water bodies in Chennai, says, “Any organisation that is willing to take up the restoration work would first have to submit a detailed estimate of the work including the time frame for completion. The government does not give blanket permission. It comes with a lot of conditions. However, these conditions are standard in nature like the removal of waste and how to handle silt from the water body. There are no exclusive guidelines for the restoration process as such.”

This leaves different organisations to take different approaches. Given this situation, Okapi Research and Advisory, an environmental research and consulting agency, and Care Earth Trust developed a science-based, easy-to-read ecological lake restoration handbook which is accessible by anyone interested in learning/implementing restoration work.

According to the methodology proposed in the handbook, the implementation of ecological restoration could be carried out in five stages. The timeline for execution varies depending on the type and size of the wetland.

Step 1: Identify candidate wetland and conduct a baseline assessment

Step 2: Assess wetland character and integrity

Step 3: Set restoration goal

Step 4: Carry out restoration

Step 5: Operationalise an exit strategy

Read more: How to go about lake restoration: Learnings from efforts in Chennai

“Every water body is unique in its own way and has its own hydro-geo morphology, demographic characteristics and a defined ecology to itself. So, all lakes cannot be restored in template format. The restoration process is akin to how the quantum of medical care varies from patient to patient visiting the hospitals,” says Arun Krishnamurthy, the Founder of Environmentalist Foundation of India (EFI), an organisation that has taken up restoration of several lakes in Chennai.

“However, certain basic standards like the amount of garbage dumped in the water body, the extent of invasive species, the structural integrity like the water holding area, boundaries, encroachments and water quality are vital and has to be looked into,” says Arun.

As for the process followed by EFI, Arun points out that the method varies from lake to lake. However, the organisation looks largely into ecological restoration since the projects they take up are not drinking water restoration projects but rather habitat restoration projects that include flood prevention and groundwater penetration.

“Ensuring structural integration of the water body, protecting the habitat characteristics, understanding the silt, sand and clay composition of the soil structure and the inflow and outflow characteristics are some of the pointers we look into while carrying out the restoration work,” says Arun.

While he points out that the indicative guidelines are nothing but a standard operating procedure, he says that no particular template of standardised methodology would suit all water bodies. He also says that the organisations carrying out the restoration work are scrutinised by the relevant department officials at all stages of the process.

A source from a private construction company based in Chennai, who worked on the restoration of water bodies belonging to both Greater Chennai Corporation and the Public Works Department, says that when they approached the local body with CSR funds, they were allocated only beautification work in the water bodies. This includes laying concrete footpaths and setting up decorative lights.

“This apart, we were asked to desilt the lake, strengthen the bunds and put up fences,” says the source. They add that they followed the instructions of the officials to carry out the desilting and bund strengthening work as they did not have anyone with expertise in the field on board.

An official from the PWD, who sought anonymity, says that when the government floats a tender, only non-structural components such as removal of waste, invasive species, desilting, bund strengthening, plantation and fencing would be allocated to the organisations.

Structural work like clearing up sluices and constructing new ones, managing inlet and outlet regulators will be taken care of by the department itself. He further added that only site-specific regulations are followed and no standardised methodology for ecological restoration is in place.

Read more: Retteri lake: The ‘heart of the community’ that citizens are fighting to save

Standardised methodology a need of the hour

“Restoration means restoring something with respect to how it existed there before. If a water body was spread across 200 acres before and now it is only in an area of 40 acres, work in the name of restoration is carried out only for these 40 acres now,” points out S Janakarajan, a retired professor from Madras Institute of Development Studies.

Very often, restoration means restoring the existing water-spread area by building concrete bunds and pathways. The structure of the original water body would have likely had a supply channel, catchment area, water spread area, sluices, surplus channel and many such elements.

“Whatever is done in the name of restoration is only an ad hoc intervention,” he says, adding that a standardised methodology should be brought in for rejuvenating the water bodies.

There is an absolute need for standardised methodology, agrees Jayshree. Different organisations take different approaches mainly because there is no standardised methodology. It depends on the professional expertise that the organisations have, their priorities and background.

“Organisations headed by ecologists or experts in the same field take up a scientific approach, and give priority to maximising the wetland area, enhancing species diversity and maintaining hydrological integrity. Others who come from different backgrounds may focus on constructing walkways, fencing and concrete bunds for strengthening. It might be right in their perspective but it does not make any sense ecologically,” she adds.

“For instance, if four water bodies in a locality are given to four different organisations, there arises a sense of confusion and bitterness among the local residents and sometimes they even get acrimonious. They ask us why we take up nature-based solutions, while others set up sewage treatment plants. This gives rise to conflict and reduces confidence on ecological restoration,” says Jayshree.

The root cause of the issue starts from the requirements stated in the tender called for restoring the water bodies. While the water bodies are connected in a cascade system, it falls under the jurisdiction of different departments of the government. These departments should work together towards a holistic approach to ecological restoration of the water bodies starting with setting some minimum standards that are common for all engaged in reviving the city’s water bodies.