Chennai’s checkered history of water management has come under the spotlight every time the city has found itself face to face with a crisis, such as the catastrophic floods of 2015 or the unprecedented drought faced by the city in 2019. Experts have repeatedly called for better management of water resources, alluding to the fact that the city’s many water bodies could be the answer to its water woes, if they are managed better. There have, in fact, been some concerted efforts in recent years to restore and manage the tanks and lakes in Chennai.

However, there are multiple organisations and departments involved, which adds to the challenge of protection and restoration. Large water bodies in the city are under the control of the Public Works Department, drinking water sources under Metro Water, temple tanks under the Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments (HR & CE) Department while the smaller lakes are managed by the Chennai Corporation.

Of these, the lakes under the Chennai Corporation have been the focus of its restoration efforts with more than 180 bodies, large and small, having been restored in the past three years with 20 more in the pipeline. While there is no list in the public domain for ordinary citizens to find out which the restored lakes are, or which are part of the larger plan, the Corporation puts out updates through their social media channels, as and when a particular restoration project is complete.

Read more: Around 100 water bodies in Chennai set to get a new lease of life; here’s how

But even as some steps have been taken to manage the water bodies, there have also been frequent complaints against encroachment and the resulting loss or shrinkage of water bodies. Allegations of encroachment automatically raise the question of comparison with original lake beds and spread. How does one know about the original spread of the lakes in Chennai? What are the tools used to map them or calculate the extent of encroachment?

Public memory

Take, for example, the slow shrinking of the Velachery Lake. It has been a subject of repeated debate with little action. Chennai lost 2389 acres of water bodies between 1979 and 2016, with Velachery lake being one of many such shrunken lakes in Chennai. Public memory has been a way of documenting the changes to the lake. The emergence of many houses and commercial establishments over what was once waterbed is common knowledge.

V Somasundaran, a retired BSNL employee, says, “I have lived here all my life. We bought land here in the 70s. Back then, when you went up to the terrace of my house you could see the sprawling lake. As more and more plots were sold, we could visibly see the size of the lake reduce over time. From where we once enjoyed the sight of this massive lake, I can now see that at least a third of it has made way for shops and apartments. Then people wonder why the area floods when it rains!”

Similar tales can be heard across the city from long time residents who recall sighting of migratory birds and enjoying the cool breeze from the lakes. Today, they find most of it built upon, their stories the only testimony to what has been lost.

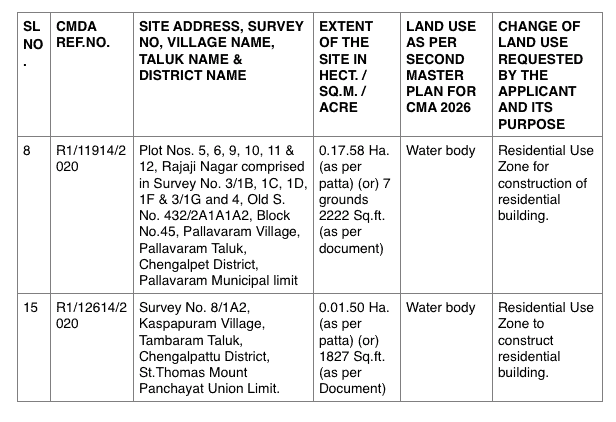

When members of Arappor Iyakkam, an NGO, came across a reclassification notification on the website of the Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority, they realised that the survey number matched that of the Pallavaram lake. They sent an objection letter against reclassifying the water body to a residential zone. Such permissions to reclassify water bodies is how lakes are encroached in small parcel. The lake in question here has already shrunk from 120 acres to around 50 acres.

Those who fight lake encroachment use public sentiment to drive their cause to a large extent. “The memories are an important part of what motivates them to fight to save the water bodies. We access land records to make our case, but sometimes even those are not accurate and cannot help us gauge the true area of the lake bed originally. In that case we have to fall back on public testimony,” says Vivek M, a resident who has been raising awareness on lake encroachment in Villivakkam.

Read more: The slow killing of Korattur Lake: Can it be reversed?

The biggest issue in lake conservation is knowing who owns the lakes in Chennai. Some bodies are controlled by the Corporation and others by the PWD. Citizens have to reach out to officials to know who controls a specific water body. “During restoration efforts, local citizens have often found that some water bodies and ponds did not appear on the Corporation’s list of water bodies under its control. In such cases we compare the revenue records and then a surveyor from the collectorate comes along to determine the boundaries before the restoration efforts are undertaken. A majority of such water bodies are located in the expanded areas that were added to the Chennai Corporation in 2011,” says a former member of an NGO in the city that was involved in lake restoration.

Where is the documentation on the lakes of the past?

Land survey records from the past are one of the key sources that can help gauge the initial areas and spread of the lakes in Chennai. These records are maintained by the revenue department. But with recent developments in technology, GIS mapping offers some of the best means to assess the true area and location of lakes and monitor any changes real time. Digitization of the lakes, however, has been happening at a slow pace.

In a recent ruling, the Madras High Court has ordered that the revenue authorities must complete digital mapping of the lakes in Chennai and make these files available to the general public on their respective websites.

What is GIS?

GIS is geographic information system used to create, manage, map and analyse various forms of data. GIS is used to combine spatial and non-spatial data and helps authorities in planning and decision-making.

“So far, we have only been relying on the revenue records to spot or quantify the encroachments in the lakes. GIS mapping is however a process that will take some time to complete accurately, it is not something that can be carried out in a few weeks’ time. Once it is done, it will also make our work easier,” says an official from the revenue department.

Empowering citizens with knowledge

While some residents are aware of the existence of lakes or encroachments, many do not know if a new plot they have bought or an apartment they have purchased is actually on land that was once a lake. “I didn’t know this was formerly a lake bed when I bought a flat here. But the flooding in 2015 was intense. We were marooned for a few days and only when I read news reports did I realise that this piece of land was once a part of the tank,” says Guru P of Perumbakkam.

But how can citizens really find out? Referring to the instance of Pallavaram Lake mentioned above, David Manohar, an activist with Arappor Iyakkam, says, “To prevent such instances of encroachment, not only do we need satellite mapping, which the authorities have been slow to undertake, we also need physical markers denoting the boundaries of water bodies. That is how every common man will know the extent of water bodies. The markings should even include encroachments, so that future buyers of the land are dissuaded from purchasing it. It is not just the lakes but the various channels that connect them that are subject to such encroachment. Ultimately, such acts are the root cause of flooding.”

On how information accessed by the NGO could be available to the common man, David says that the process is labyrinthine. When they come across any instance of encroachment, the group obtains the maps from the revenue department using the survey numbers and compares them against the ground situation. In other cases they have had to file RTIs to obtain such information. It is a process that involves chasing blind leads and knowing where to look. This problem could be solve by simple marking of boundaries over not just lakes but all commons. Right now, in David’s words, it is all “a mystery”.

How feasible is lake mapping?

For GIS mapping, capacity building is a key requirement. Raj Bhagatt, Senior Manager of WRI India, says “We have records for all resources but the digitisation of such records rests entirely on the initiative taken by the local authorities. A structured effort to digitise records will involve coordination from multiple departments. While not impossible, it will require a proper plan from collation to application. Right now it is hard to access even basic information such as district boundaries or town/village/ward boundaries.”

For citizens to benefit from the availability of such information, Raj says that the only way forward would be to open source the data. Open data will allow access to those who seek to learn more about the resources and help in their cause for conservation. He speaks of the efforts of GIS mapping done in Karnataka that could serve as a blueprint for Tamil Nadu if the state chooses to undertake large scale digitisation. Spatial data there is available to all, not just the officials and select few individuals.