Residents of Chokkanahalli and Sampigehalli have been fighting to save their neighbourhood lake, Venkateshpura Kere. The lake was listed as 10 acres 35 guntas by BDA and BBMP until a few years ago, but has slowly been reduced to 6 acres and 35 guntas on paper. Read more about this in part 1.

The remaining four acres, which comprise the lake watershed area, has been notified as a Civic Amenity (CA) site by BDA; part of this has been leased to a private trust. BBMP, which is the custodian of the lake, has done little to address the concerns of the residents or explain how the lake’s area was reduced.

The Chokkanahalli Sampigehalli Abhivriddhi Forum (CSAF), a residents’ group, has been asking the BBMP and BDA to conduct a fresh survey and protect the entire lake. At stake, according to the residents, is biodiversity, loss of grazing land, and a historical monument.

Sampigehalli Auxiliary Tower Station: Remnants of scientific history

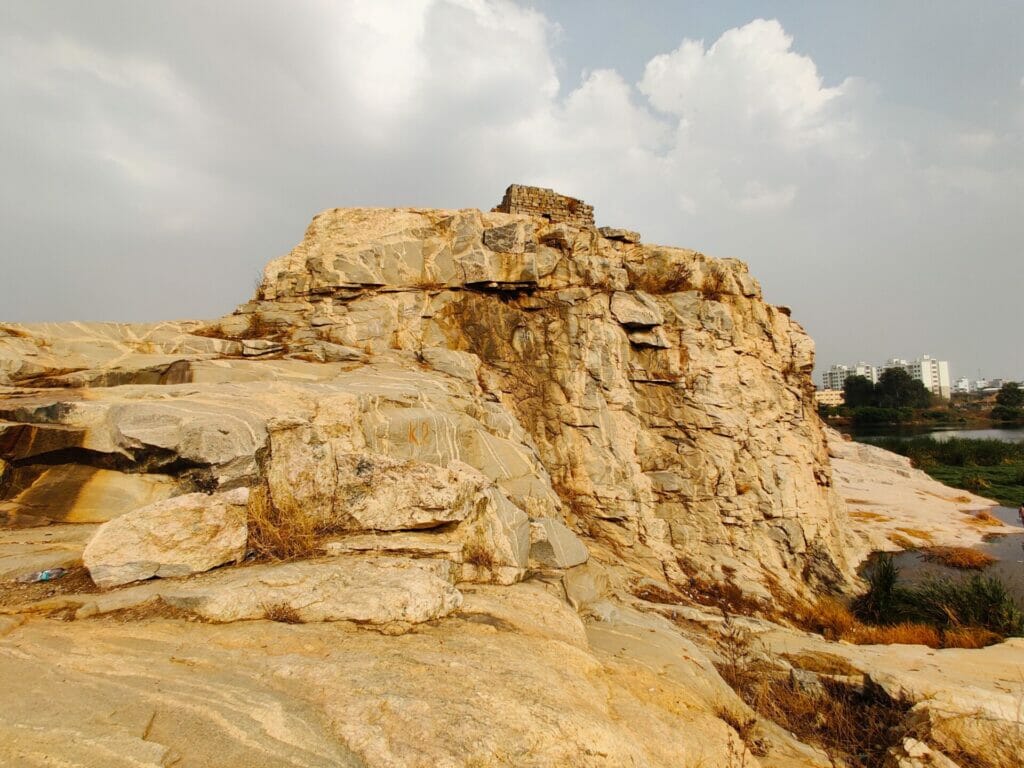

Overlooking the lake is a small hillock, which rises into the Sampigehalli Auxiliary Tower Station. It is hard to miss the distinctive structure from any side of the lake. A rocky granite outcrop ends with a small square tower at the peak.

On this tower would have stood a tall, narrow survey tower, which would have aided in one of the most ambitious mapping projects known to mankind: the Great Trigonometric Survey.

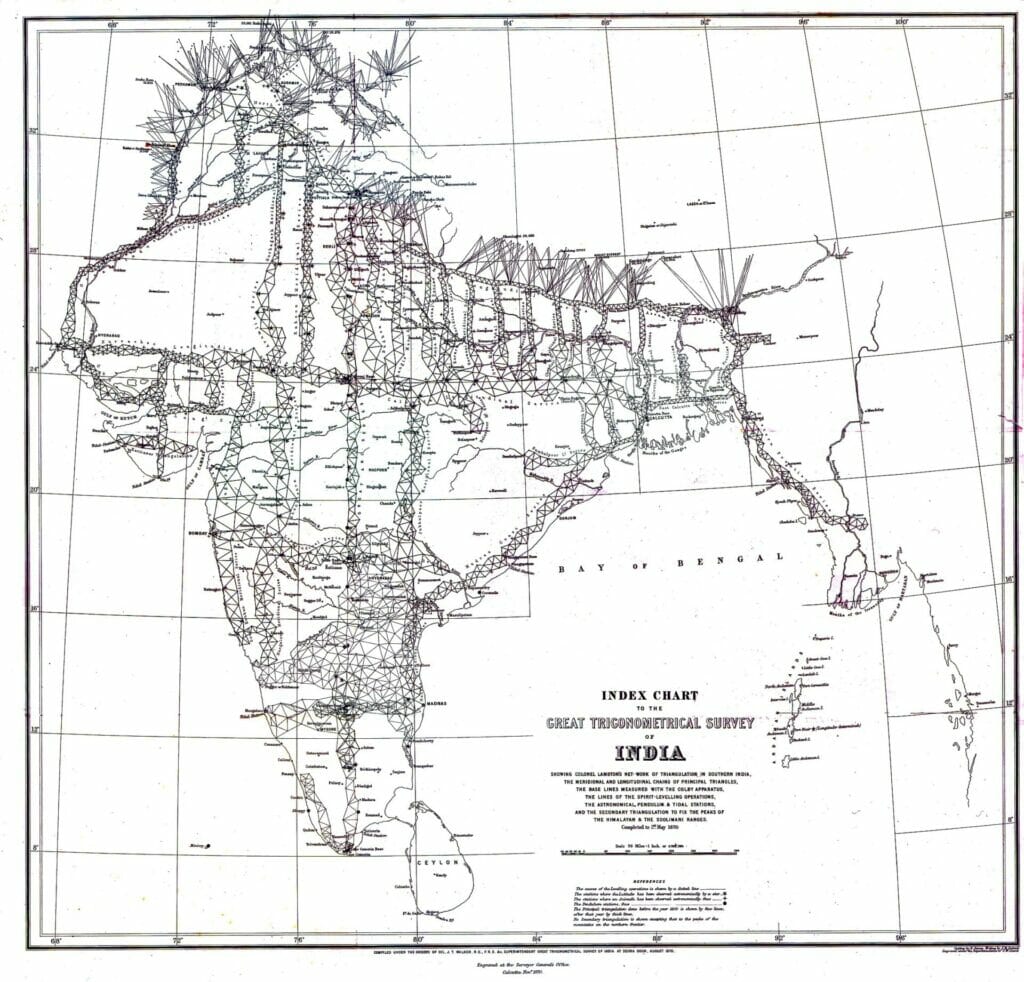

Between 1802 and 1873, the British undertook a mammoth task to map the entire Indian subcontinent. To do this, they used the process of triangulation. Triangulation is a method in trigonometry that allows us to use the known distance and angle between two points to calculate the distance to the third.

Using instruments set up on top of the survey tower in Sampigehalli, surveyors would have figured the distance to two other visible elevated points, such as other hills or towers, thus forming a triangle. Each point of the triangle would have been used to triangulate the distance with a new point. The entire Indian subcontinent was, thus, covered with triangles, used to measure the distance between every city and the height of every mountain.

The survey helped record the height of the Himalayan range, including Mount Everest. The measurements were also surprisingly accurate. Measurements of Mount Everest were only a few inches off when compared to actual height recorded nearly two centuries later.

“This was a huge undertaking, especially considering it was the 1800s,” says Meera Iyer, convenor of the Bengaluru chapter of Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH). “And what makes it all the more special is that the actual survey started in Bangalore,” she adds.

GTS is part of Bengaluru’s scientific heritage

A researcher and writer, Meera calls for the protection of the Sampigehalli Auxiliary Tower Station. Although the survey covered every inch of the subcontinent, very few physical remnants of the project exist, she explains. “The Sampigehalli Auxiliary Tower Station and another station in Kannur (Hennu-Bagalur road) are one of few remnants left in the country.”

Apart from being a relic of Indian history, Meera sees the Sampigehalli tower as symbol of Bengaluru’s scientific ambitions. “The initial impulse of this whole exercise (GTS) was to figure out the curvature of the earth. So, from the beginning it was a scientific enterprise,” she says.

“We pride ourselves on being a ‘science city’ and a knowledge-based economy,” she adds. Remnants of GTS fit well with this image of the science city that we want to project to the world. “Of course, we should be protecting this remnant of a scientific enterprise,” she says. “We should be celebrating it.”

Read more: Why cities like Bengaluru fail to protect heritage

A vision for Sampigehalli Tower

While Sampigehalli Tower is not within the 2.75 acres of alleged lake land allotted to the private trust by BDA, the tower is adjacent to the site. Indeed, the tower is part of a natural rock structure that is within the disputed site. The rocky outcrop allotted to the private trust is being steadily broken down.

Harish Raj, owner of Siddheshwara Education Trust, which has been granted this land on a 30 year lease, confirmed that the rocky outcrop, within the site, would be broken down and the land flattened. Residents, who are part of the CSAF, fear that this fragile historical monument will become structurally weak, because of the JCB action on the connected rock.

Harish disputes this. “This area was previously a quarry, and nothing happened to the tower. It survived blasting. Why should a few JCBs do any damage?” he asks. Harish also claims that the tower would be protected by his trust, even though the monument was not within the leased land. However, he declined to go into details of how the monument would be protected.

Meera’s own vision is a simple park around the monument and signage that helps people understand the history. “People will come. There will be curiosity. We could bring school children there, talk about GTS and the scientific history of the city,” she says.

Read more: “It’s a fight to preserve our heritage,” says architect restoring 112-year-old Fort High School

The loss of grazing land

This sort of a vision for a historical heritage site also being part of public spaces appears to be more in line with the vision that the residents of the area have for the space. One of the concerns that CSAF has is the privatisation of what they see as public commons.

The land that they allege was part of the lake was declared as gomala land or grazing land by the BDA, says CSAF. “But BDA claims that no grazing happens here. There are no cows in the area,” says one member, recounting meetings with BDA officials. This justification was used to notify the land as a CA site, they allege.

However, it is clear that the rural residents of Chokkanahalli and Sampigehalli do indeed use the land and surrounding areas for grazing cows, goats, and sheep. Sampigehalli also has a milk diary. At least some of the villagers from Chokkanahalli are unhappy about the BDA’s plans for the area and the leasing of land to the private trust.

Kannappa, a resident of Chokkanahalli village, remembers when the entire area was covered by huge rock faces. The 70-year-old worked in the quarry that brought down most hills in the area. The rocky outcrop with the GTS tower is all that remains, he says. According to Kannappa, the quarry and surrounding land belongs to Chokkanahalli village. The quarry was filled up by the BDA in 2019. The entire area, including the now filled up quarry, is important grazing land, according to the elderly villager.

Kannappa and his fellow residents from Chokkanahalli worry that with private entities cordoning off areas, their grazing land would be lost. I met two women from Chokkanahalli grazing goats who expressed the same concern. The women, who did not wish to be named, said they had been told to keep their goats away from the CA site by unknown individuals. I could not confirm if the private trust had told grazers to keep away.

According to Harish, BDA has given part of the CA site to the trust and allotted the rest to BWSSB to build a water tank. I could not independently verify this claim.

Public commons, not private trusts

CSAF members assert that any development in the area should not take away the grazing rights of the villagers, who were there first. They also question the need to allot civic amenities land to private entities. Harish brushes this question aside as jealousy.

Harish claims that the trust would provide an important service to the community by building a school. “We are going to build a world class CBSE school. This neighbourhood needs one,” he says. However, he did not respond to my queries of whether this school would be free for students from the villages and lower income settlements in the area.

One CSAF member feels a private school is not a service to their neighbourhood. The members point out that the area’s only functioning government school did not have any playground. “Why can’t CA sites be used to build a public playground for these children so they can play sports?” he asks. Another resident suggests a public park around the GTS to go along with the playground. “Civic amenities should not just be for the rich,” says the first CSAF member.

Very good detailed reporting..Needs amplification to reach the “deaf” ears of authorities involved..

The school will generate money for Harish Raj and his friends with no benefit to the local community. And how is it legal for the BBMP to reduce the size of a lake? Don’t they have any concern for the sustainable future of our land?

Very well researched and detailed article. Hope it reaches the authorities and some action is taken. At this rate the public will have no common spaces left!

In other cities globally, former grazing lands are given ‘Protected/Green Buffer’ status once those regions urbanise. London is as big and populated as our city, but green buffers do a great job to keep London liveable. In Bengaluru, BBMP & BDA simply turn them to land sharks.