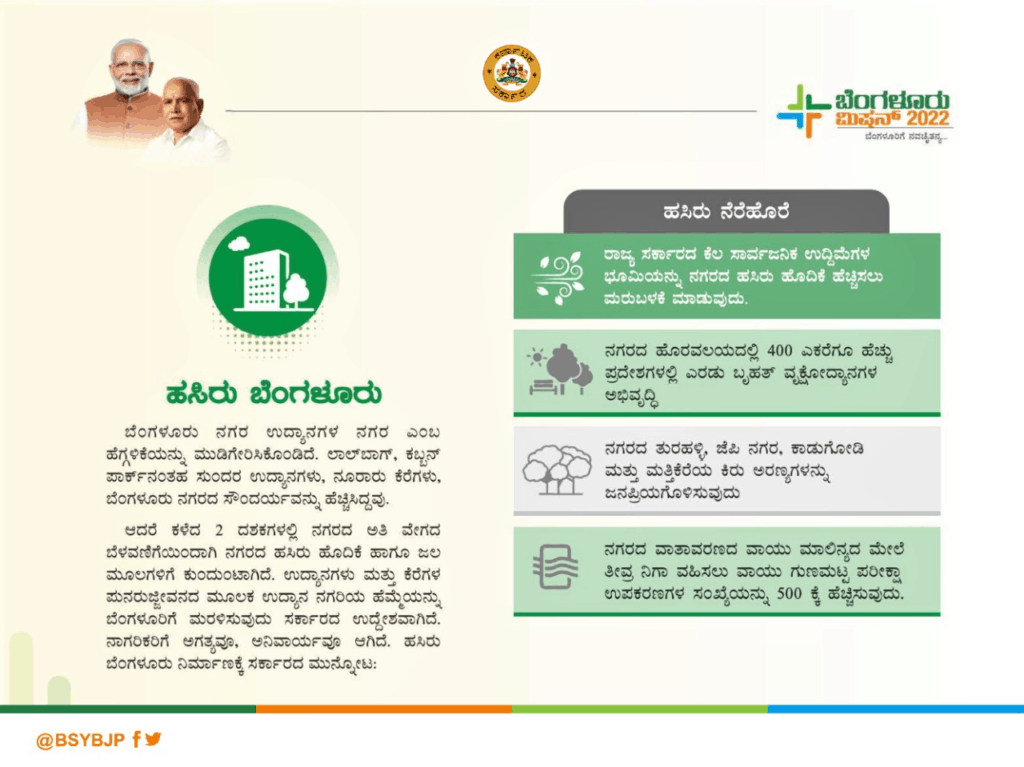

Bengaluru Mission 2022 is the state government’s plan to transform the city’s infrastructure, enabling faster commute and providing a cleaner and greener city. It was unveiled by Karnataka Chief Minister BS Yeddiyurappa in December last year.

The proposed plan includes the creation of new urban lung spaces in existing mini forests in and around the city. Going by the Chief Minister’s tweet, parks/gardens like Cubbon Park and Lalbagh are cited as models for lung spaces.

Bengaluru Mission 2022 envisions turning a natural forest — the popular Turahalli forest on Kanakapura Road, south of the city — into a tree park. It entails converting 400 acres of the 597-acre scrub and rocky jungle into a public park with ticketed entry. There is, still, no detailed project report that the government has placed in the public domain.

The proposed tree park is expected to have amenities including 10 km of walkways/paths, entry arch, toilets, canteen, parking lot, children’s play area, senior citizens’ gym, and yoga spaces.

Is this the need of the hour?

Environmental activists, naturalists, rock-climbing enthusiasts, birders, walkers and residents living close to Turahalli forest have strongly opposed such development. To begin with, they say that the government’s plan violates Section 2 of the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980, and several other Supreme Court orders.

They have sought immediate stoppage to the ongoing “destruction” at Turahalli, and hold the forest department responsible for the violations.

Citizen Matters has invited a diverse panel to discuss the implications of converting this natural habitat — complete with its flora, fauna and its own ecosystem — into a tree park. At a point in time when the effects of climate change are clearly visible on a day-to-day basis, is it prudent to interfere with one of the last remaining forest patches around Bengaluru?

What role should the government — through policy/legislation/enforcement — and civil society, play in preserving this unique heritage?

Also, can we discount the fact that there are no green spaces in the city where people can connect with nature? Should it be conserved as a natural environment and a public space, without turning it into a manicured and ticketed garden?

What is the Turahalli that Bengaluru needs? And, how should that be created? This will be the focus of the panel discussion.

Date: February 17, 2021

Time: 5:30 pm

Register here: https://forms.gle/RQRF5qwKV4DfMv7K8