In a narrow gully in Thane’s Vartak Nagar, a small home-based unit of a contractor is also the assembly point for the area’s women to gather and take raw materials to make keychains. The contractor weighs and counts the keychain parts before wrapping them in a plastic bag. He notes the quantity in his diary and a small notebook that each woman carries with her.

“Kal ka kitna bana (How many did you make yesterday),” the contractor asks each woman, who deposits the previous day’s keychains with him as he again records the quantity they have submitted. The women take raw materials like shells, bells, rings, buckles and other decorative paraphernalia used to make colourful keychains. Each keychain is carefully assembled by the woman who sits down for long hours to make them using pliers and scissors.

The same keychains, sold in local trains, shops, and streetside stalls, are made in the homes of women living in slums. They are an unrecognised, highly vulnerable and silent task force that toils the entire day to assemble finished products, which are then sold in the market by contractors and suppliers.

Home-based piece rate work

Piece rate work is work remunerated per piece, instead of a fixed monthly salary during fixed hours. The International Labour Organisation classifies home-based work as “workers who carry out remunerative work within their homes or in an adjacent location or in any location that is not the workplace of the employer.”

“I earn Rs. 800-900 per month,”, said a young woman in her early thirties, refusing to be identified as she is afraid that her family might find out and stop her from working. Making a dozen keychains fetches her Rs. 2.5 and the final product is sold at Rs. 10-20 per piece. It means that 97% of the money goes to others in the supply chain, like the producers making the raw materials, the contractors fetching the raw material and the supplier selling the finished product to sellers who sell it in different public spaces.

Challenges

“Kucch auratein bana leti hain 50-60 sets, par uske liye continuous 2 se 3 ghanta baithna padta hai. Itna sabke paas time nahi hai (Some women make 50-60 sets, but for that they need to sit for 2 to 3 hours straight. Not everyone has that much time),” said the contractor who manages the shop, which is also the entrance to his home on a higher level. The shop is a tiny hole in the wall in between other establishments, but big enough to run an entire business for the contractor. He adds that if a woman works for a whole day, she can also make 100 sets.

Toiling for entire days making keychains can fetch them around Rs. 7,500 in a month, which is not enough to cover any monthly expenses. This can at best be supplementary income that women use for emergencies or as a backup. Home-based work is not a sustainable source of income, simply because the “per piece rate” is very less.

Health hazards

Workers complain about long hours of sitting and bending, and eyesight problems as homes in slums are poorly lit. The onus of treating any injuries caused due to needles, scissors or other grievous injuries falls entirely on the workers.

What might seem like a small task – pulling loose threads from saris – causes women workers to lose sensation in their fingers. No protective equipment or compensation is provided for such physical discomfort.

Anonymity and vulnerability of the workers

Home-based work is a financially risky business, as there is no written contract between the workers and employers. It is made riskier, as many women hide their work from family members. Most of the women who spoke with Citizen Matters were reluctant to share their stories due to the shame of being involved in such a low-paying business and the fear of losing their meagre earnings. The presence of the contractor nearby also made the workers nervous, as they didn’t want to do or say anything that would cause them to lose their source of income.

Home-based work and gender

Women take up home-based work along with household chores, like cooking, cleaning, washing clothes, bathing children, dropping them to school, and taking care of their husband, who comes back home from long work shifts spanning more than 12 hours. They take breaks in between these demanding chores to do piece rate work. Others are domestic workers, who work during the day and come home to assemble keychains.

“My friend, who has a young school-going child, picks up the raw material while she heads home after dropping her child at the municipal school nearby,” said a young worker who had come to the shop to collect raw material, preferring to stay anonymous. “When her child is at school, she uses the afternoon to assemble keychains.”

Minute tasks, which are crucial links in the supply chain, like sticking stones on sarees and bangles, making anklets, cutting bra straps, pulling threads, making keychains, etc, are some of the many different tasks that home-based workers, primarily women do. This work has sent many women back to the domain of the home, as factories have now started bringing work directly to the home in a highly fragmented manufacturing supply chain.

Read more: Workers at labour nakas in Thane mirror an unpredictable, exploitative system

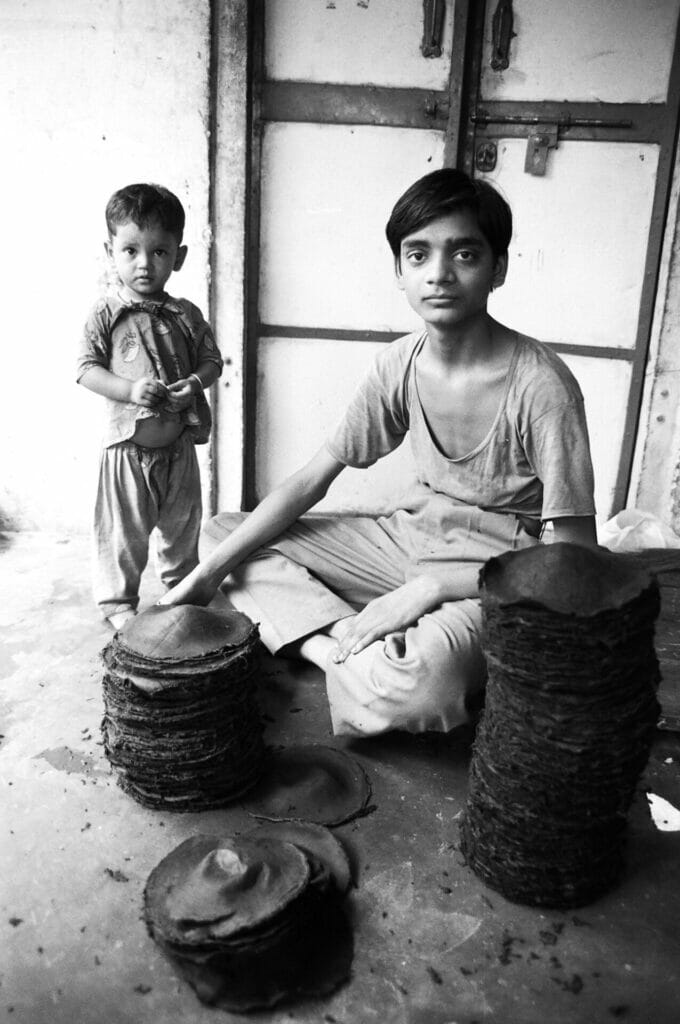

Home-based work and child labour

Home-based work frequently involves children in the house contributing to the work, which keeps children away from education. As workers are paid as per the quantity produced, children are involved in the work to ensure they earn at least a small amount every day. Increased school dropout rates during COVID-19-induced lockdowns also contributed to an increase in child labour, with many children pushed into home-based work.

Mumbai’s piece rate home-based work industry supply chain

The contractor in Thane’s Vartak Nagar purchases raw material from the local market and sells the finished products in Sutar Gully near Jhaveri Bazar in South Mumbai. This is true for the garment sector, jewellery business, show pieces business, hosiery units and other small and medium enterprises which rely on piece rate home-based work.

Supply chains are extremely fragmented with a lot of the finished products packed and shipped outside the city for sale. Workers have no option but to accept the meagre wages they receive, as poor income is better than no income. This is why a walk through any gully in a slum will show women painstakingly sticking stones on kurtas, making diamond-shaped beaded curtains, painting diyas and other such home-based work paying by the piece.

Piece rate work is a tactic used by the employer to ensure that he profits at the cost of the worker, who is paid poor wages and by the quantity. They are forced to make more products to earn more.

To ensure that the employers are also accountable to the employees, women workers should get wages that allow them to sustain themselves and their family, enable them to step out of the domain of the kitchen and children, and truly allow themselves to realise their goals as socio-economically liberated women.

Only this way can one ensure nutrition, health and education for the next generation.