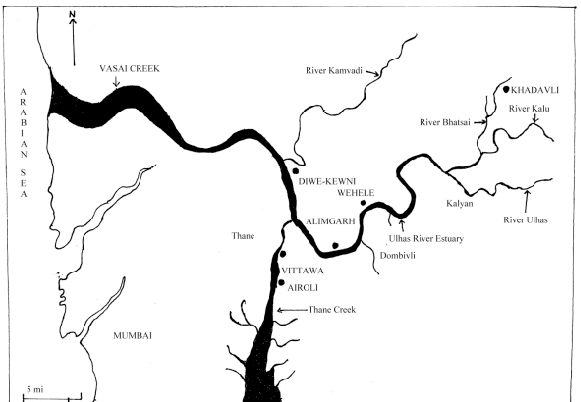

You’ve probably seen the Ulhas river on your escape from the city, as it flows through Mumbai’s favourite holiday haunt in Khandala valley in interior Karjat. But there is a lot more to the river, which originates in the Sahyadri hill ranges of Raigad district to the south of Mumbai. It is fed by multiple small rivers, rivulets, and streams and then flows through Neral, Badlapur, Ambernath, Ulhasnagar, and Kalyan. Before joining the Arabian sea, it splits at Balkum, one going to Vasai creek and the other to Thane creek.

The river supplies drinking water to 45 lakh people in Kalyan-Dombivli, Ulhasnagar, and parts of Navi Mumbai, covering 4,733 square km.

Throughout the years, however, the rapid urbanisation and industrialisation in the region has changed the face of the river and wreaked havoc on the lives, humans and fauna, dependent on it. Here is the story of the destruction of the Ulhas river.

The journey of Ulhas River

40 years ago, Kalyan hardly had any buildings; it was dominated by the Koli community, who are traditional fishermen. This would all change with the establishment of the Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation (MIDC) in 1962, with the goal of attracting investment and creating jobs.

They began by laying down the Kalyan-Shilphata and Kalyan-Dombivli roads in 1964. Industrial plots, sheds, residential and commercial plots were demarcated and developed as Phase I and II and a residential zone.

Once paddy fields are now encroached upon by giant builders to construct multi-story buildings catering to the ever-increasing urbanisation of Mumbai. As peri-urban regions, Kalyan and Dombivli suffer the spillover of the demand the region attracts. Due to cheaper real estate rates, electricity subsidies and an easy one-hour commute via local trains free from traffic, it provides a similar standard of living at cheaper rates.

The river as habitat and livelihood

The catchment area of the river has many wetlands in the form of paddy fields, lakes, oxbow lakes, etc. The host migratory birds like cranes, flamingos, and golden Orioles; local birds like the egret, storks, Indian Robin, Indian drongo, Jacobin cuckoo, and waterhens are frequently sighted.

The Ulhas river drains in the Arabian sea through the Vasai creek, after slightly touching the Thane creek’s salt water near the Kalwa region. During high tides, the mingling of salt water in the river till the Kalyan-Dombivli region creates ideal conditions for mangroves, which are safe nesting and roosting sites for birds and spawning grounds for fishes. The banks of the Ulhas river used to act as a passage to the Vasai and Thane creeks for the fishermen of the koliwada.

However, illegal sand mining, encroachment, and pollution have destroyed their livelihoods as the number of local species of freshwater fish is diminishing.

Encroachment of river banks has created small ponds out of the river’s edges, cutting them off from the main channel. These, called oxbow lakes, are seasonal and highly threatened; locals treat them like dumping grounds. The result is highly polluted water.

Destruction of wetlands

These wetlands have played a vital role in carbon sequestration over the years. Today, however, all that work is being reversed. Wetlands are randomly filled with construction debris to flatten the land, buttering it up for development. Later, the debris is removed with the help of heavy machinery.

To make the foundation for buildings, these erstwhile wetlands are dug indiscriminately as deep as two to four floors below ground level, until firm land is found. The wetland is essentially wiped out, wiping out all the biodiversity dependent on it. Whatever carbon dioxide was captured and stored is released back into the atmosphere.

Apartments constructed on wetlands are far more expensive than apartments built on firm lands. This is a double whammy for residents, who face rising prices and unsustainable practices that lead to climate change and global warming. They are at a higher risk of damage during disasters like tsunamis, cyclones, etc., as the foundation is not designed considering its environmental vulnerability and the impact of hazardous footings.

There is also the added layer of corruption and bribery these buildings stand on. Builders do not have environmental clearance. In 2019, the collapse of a 30-year-old building led to the loss of three lives as authorities failed to vacate the structure.

Read more: What the Mangrove Alliance at COP27 could mean for Mumbai’s mangroves

Invasive species

Untreated sewage from nearby apartments accumulates in the Ulhas river and its adjacent water bodies, and acts as a breeding ground for invasive aquatic weeds, hyacinths, duckweed, etc. A thick canopy prevents sunlight penetration and threatens the survival of local sweetwater fishes, crabs, etc. The ponds, which provided an ecosystem for filtering water are now highly polluted, causing irreversible damage to the mechanism itself.

In 2016, an activist, Nitin Nikam, held a protest for 16 days against the discharge of domestic and industrial waste into the Ulhas river. The polluted water from the textile industries of Ulhasnagar, nullas of Ambernath and chemical factories of MIDC in Dombivli is discharged into rivers across its course. The water hyacinth, an alien species which is an indicator of heavy metal pollution, had engulfed the river.

In response, the Kalyan-Dombivli Municipal Corporation (KDMC) and Ulhasnagar Municipal Corporation assured the construction of sewage treatment plants to treat the polluted water discharging from the city into the river.

But with no action taken again the pollution, another protest was organised in 2021 by NGOs, including Mee Kalyankar, Ulhas Nadi Bachao Samiti, and Waldhuni Jal Biradari. In Kalyan, under Nitin Nikam’s leadership, a dam agitation was started.

A year later, on 10th February 2022, the district administration declared a 30 km stretch of the Ulhas river, from Kalyan to Badlapur, free from water hyacinth. They had contracted a Nerul-based foundation for the cleaning, using drone technology to spread chemicals. However, activists still claim the river is not free from pollution.

The responsibility of keeping rivers clean

Water conservation is a multi-stakeholder approach. It cannot be done without government collaboration, considering the decentralised nature of its existence in various forms, including groundwater and surface water. NGOs and civil society organisations cannot continue efforts their without sustainable financing models, considering the time and effort it takes to approach the government and convince them of its seriousness and take.

The persistent efforts by citizens and organisations will only see incremental improvement in the condition of the rivers. While government authorities need to be more transparent on the measures taken and budget allocation, industries need more accountability to the pollution control board and local authorities.

In India, till 2015, river regulation policy protected the rivers from pollution and attempted to keep floodplains clear by declaring a buffer area of 1 km area around it as a no-development zone and prohibiting industries from 500 meters of rivers. However, in 2015, the policy was rolled back without convincing and rational reasons, and alternative guidelines opened doors for further destruction.

While the judiciary has noted the diminishing river’s seriousness, it has taken punitive and advisory measures. However, it is crucial to have an expert intervention for watershed development, holistic water conservation, and management of resources. Under Article 48, it is the responsibility of the constitutional government to protect the rivers.

A case study for reversal

While it may seem like the situation is beyond the point of no return, reversal is possible. An instructive case study for how is the restoration of the Thames river in London. Far from the pristine blue waters it is today, it was highly polluted in 1858. The usual suspects of industrialisation and urbanisation were to blame, causing such a great stink so as to drive people out of the city.

How did authorities manage to reverse the sins?

Starting 1976, all sewage was treated before entering the Thames. Legislative interventions such as the Rivers Pollution Prevention Act, 1961; Public Health (Drainage of Trade Premises) Act, 1937; River Boards Act, 1948; Prevention of Pollution Bill, 1961; and the British Waterways Act, 1995. In 1989, the National Rivers Authority privatised water companies, directly leading to the improvement in water quality. Recently, a 25 km “super sewer”, the Thames tideway tunnel is being constructed under the river and is expected to be complete by 2025 to intercept, store and transfer sewage.

The river was monitored to measure and rate pollution, lower scores indicating that organisms would not be able to survive. Some technological interventions, like large oxygenators, or ‘bubblers’ aided this by increasing dissolved oxygen levels.

These interventions took six long decades to restore the river. But today, over 120 species of fish are recorded in the river regularly, with occasional sightings of exotic species. If the Ulhas river is to be saved, action needs to start now.

[The author has written this article as a resident on the bank of the Ulhas river and a patient observer of the evolving landscape over 10 years.]

Excellent Study of Ulhas River.A Phd Material, almost every aspect

geographical, eviormental,GOV. Policies, Negligence of Town Planning authorities ,Commercial ,NAME HAS BEEN anysied. India Needs Nity Shetty at Macro level City Commission .

Instead of “In India, till 2015, river regulation policy….”

It should be

“In Maharashtra, till 2015, river regulation policy….”

thank you for your mail. will correct.

warmest,

prachi